Materials have historically been treated as stable substrates—chosen, specified, and deployed to perform predictably under known conditions. That assumption is increasingly inadequate. Across architecture, textiles, and industrial design, materials are now developed to behave: to respond to environmental stimuli, to change state over time, and to be tuned through computational feedback rather than fixed recipes. Beyond aesthetics, this behavior is structural. It reshapes how performance is specified, how failure is assessed, and how responsibility is distributed across design, fabrication, and maintenance.

Rather than designing a finished form, practitioners are increasingly defining behavioral envelopes—ranges of action materials can perform under varying conditions. Intelligence, in this context, does not necessarily mean embedded computation. It often resides in geometry, composition, fabrication logic, or in the workflows used to discover and optimize material properties.

Programmable textiles beyond embedded electronics

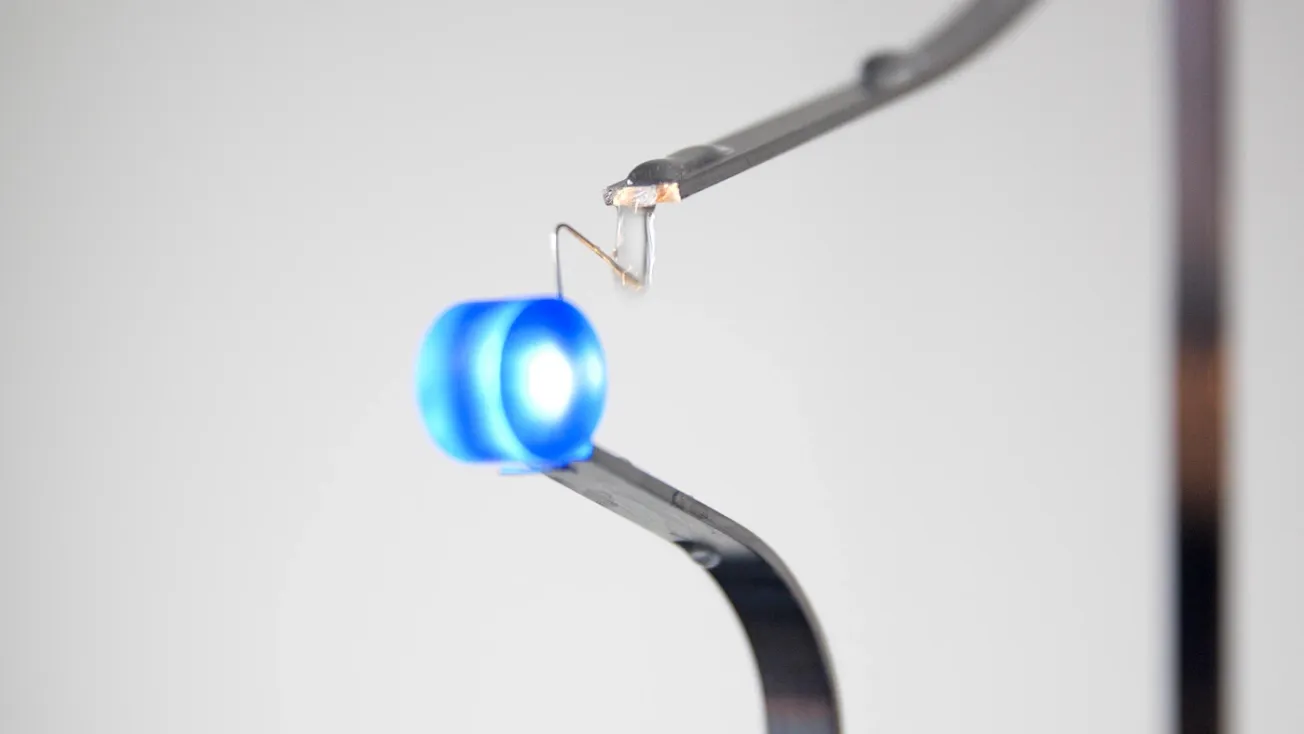

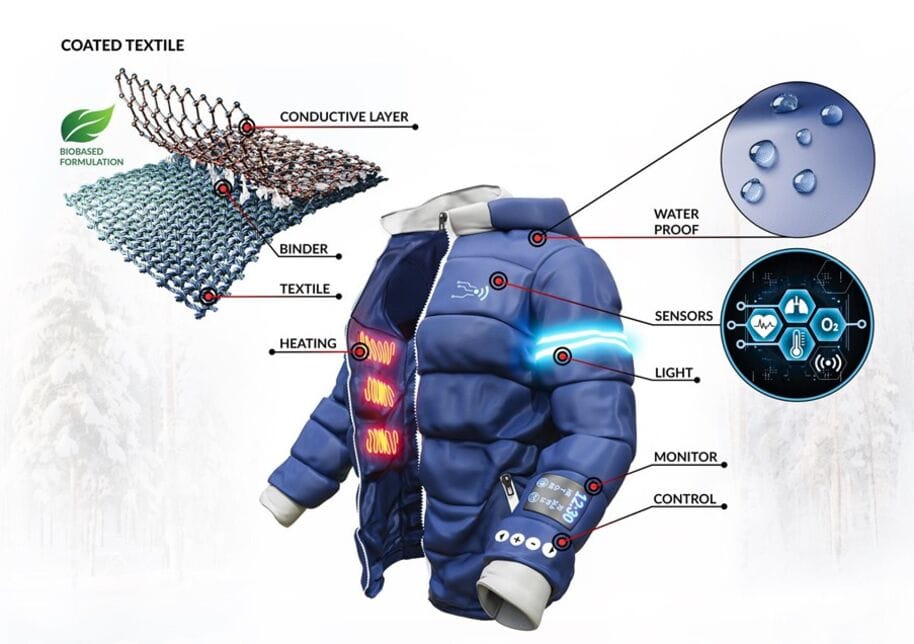

Smart textiles were historically dominated by add-on approaches—sensors stitched into fabric, electronics laminated onto garments, and conductive threads treated primarily as carriers for hardware. Current research increasingly targets the material substrate itself. At Aalto University, projects such as SuperTextil investigate conductive, bio-based textiles using scalable graphene coatings, targeting functions such as electrical heating and sensing while reducing reliance on metals and discrete electronic components. The project foregrounds research priorities including durability, washability, and compatibility with existing textile manufacturing processes.

In parallel, Aalto’s AI-yarn project applies machine learning techniques to textile material development itself. Rather than relying solely on manual trial-and-error, researchers use computational optimization to explore how variables such as coating thickness, material composition, and processing parameters influence performance outcomes. Here, “intelligence” resides not in the fabric alone, but in the development pipeline that shapes it.

Taken together, these efforts point to a broader methodological shift. Materials are no longer specified solely through fixed recipes; they are increasingly developed through data-driven iteration, with designers working alongside scientists and engineers to define target behaviors rather than static characteristics.

Self-transforming systems and programmable matter

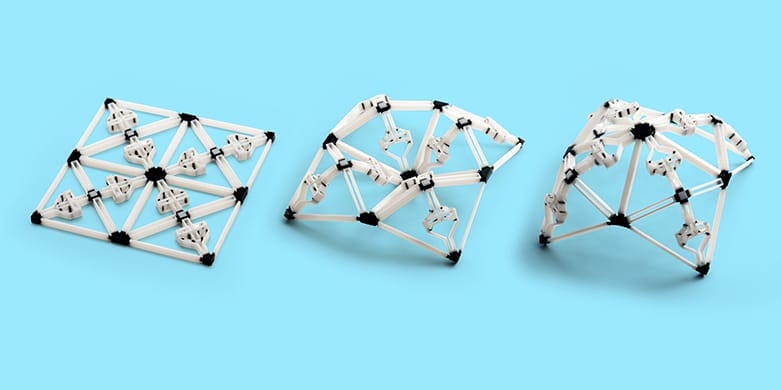

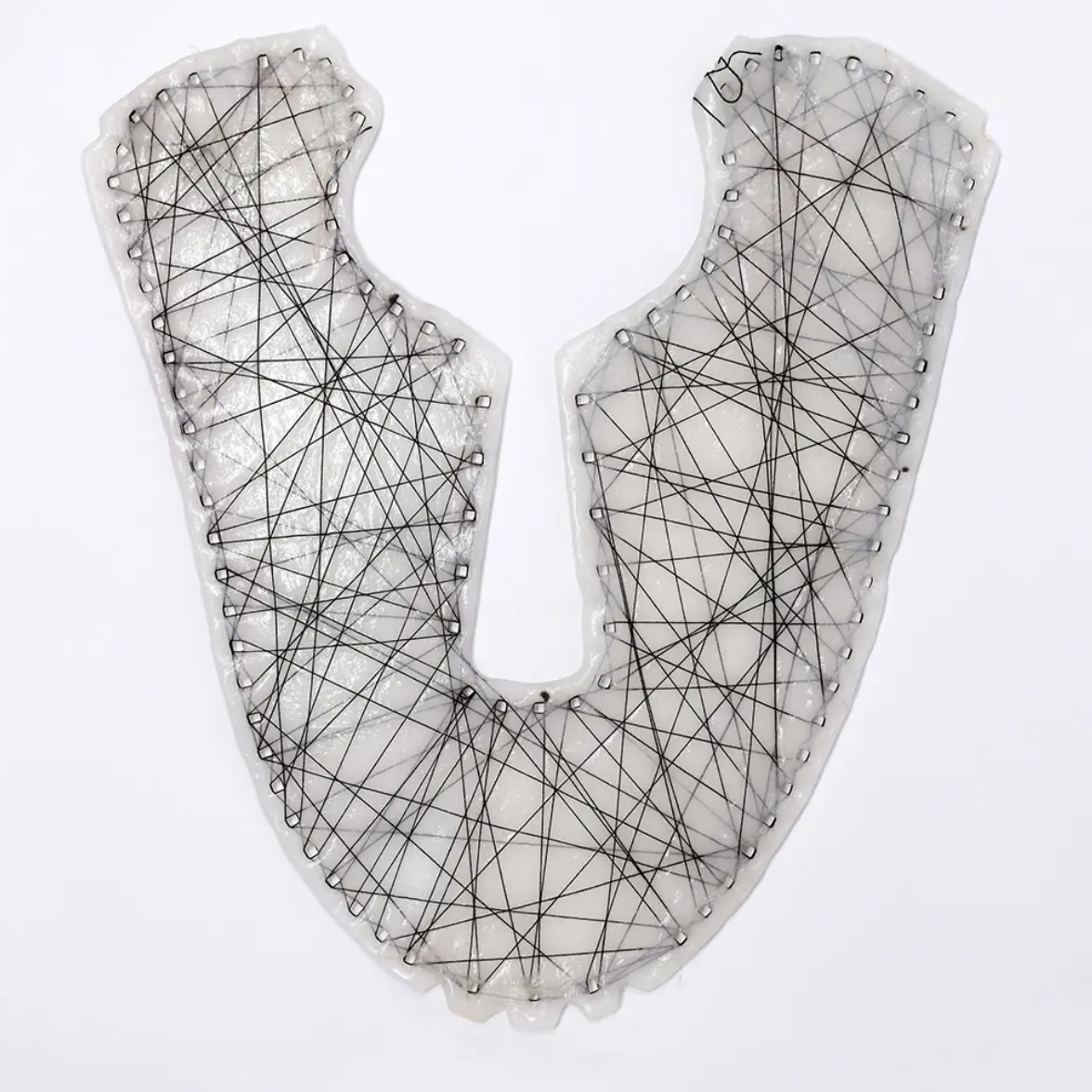

Among the research groups shaping contemporary discourse on programmable materials is the MIT Self-Assembly Lab, led by Skylar Tibbits. The lab’s work focuses on engineered systems designed to change shape, properties, or function in response to external stimuli such as heat, moisture, or mechanical force.

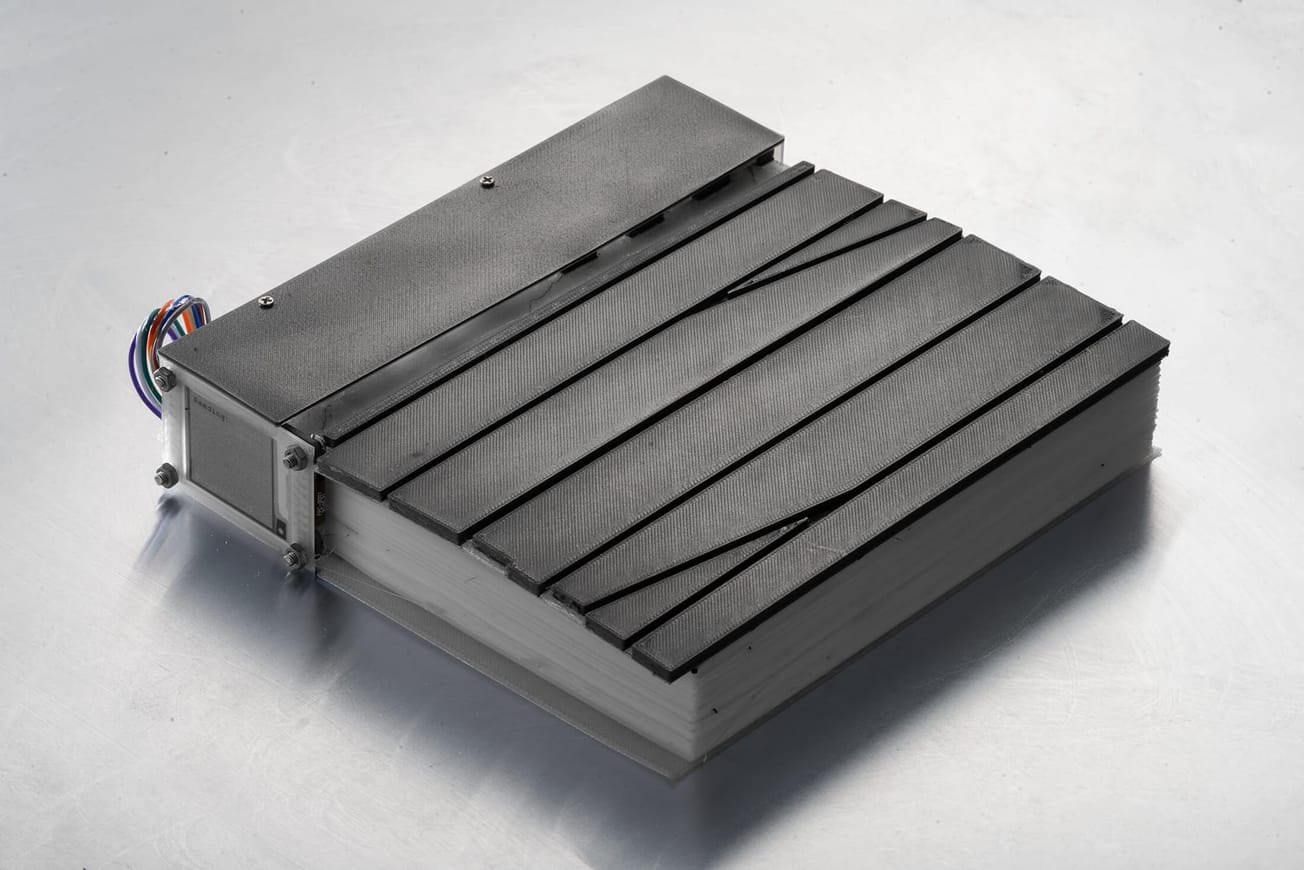

Image Credit: No Foam KNIT, MIT Self-Assembly Lab

Importantly, these materials are not framed as autonomous or “alive.” They are deliberately constrained systems whose behaviors are specified in advance. The central design challenge lies in determining how and when transformation occurs, and in ensuring that such changes remain legible and predictable. This requires a form of design literacy that integrates material science, computation, and fabrication logic. For architecture and product design, the implications are significant. Walls, panels, and textiles can no longer be evaluated solely through static metrics. Performance unfolds over time, making testing, simulation, and verification integral to the design process.

Fabrication workflows catch up to material complexity

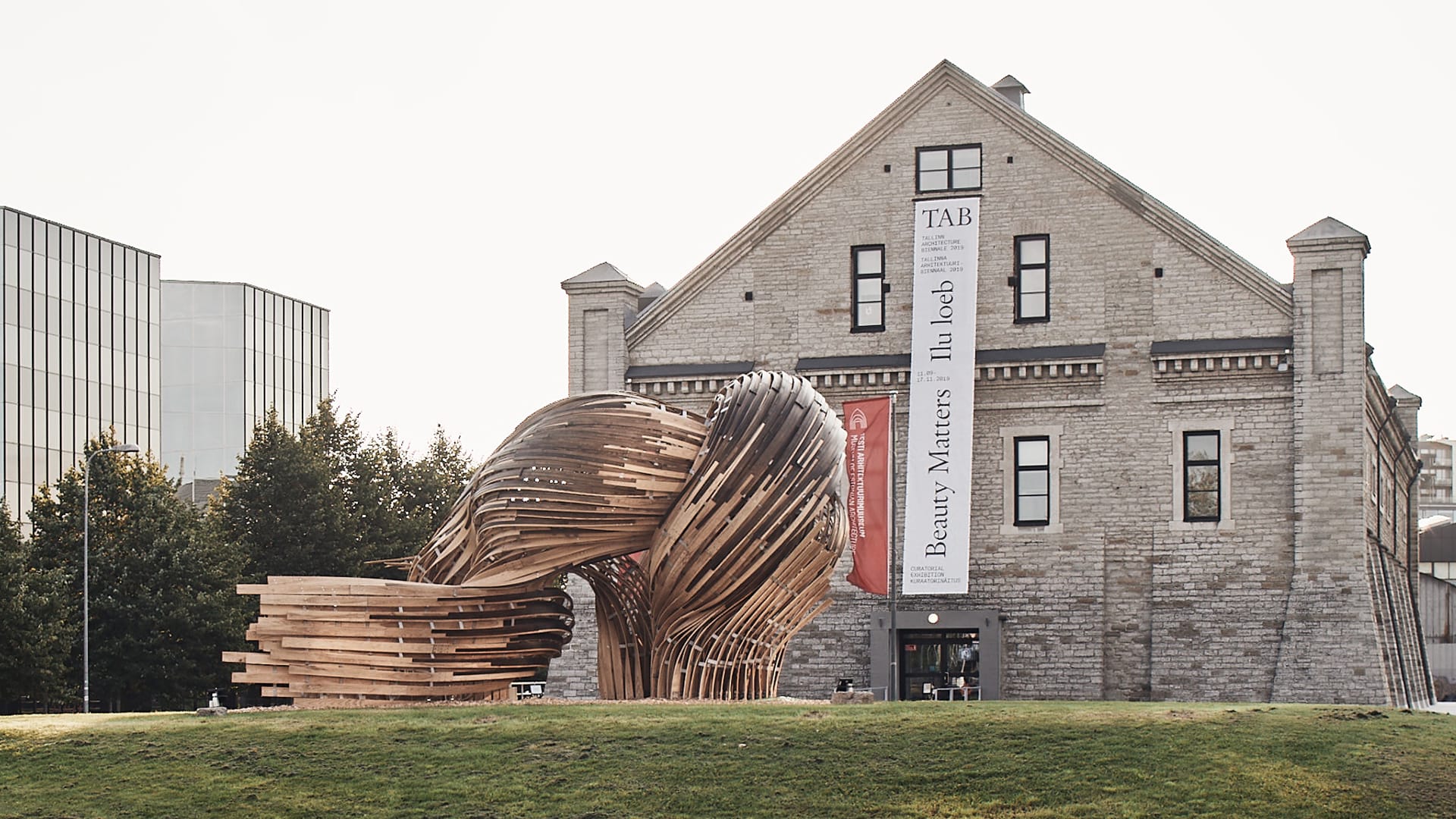

As materials become more behaviorally complex, traditional construction documentation often struggles to keep pace. Soomeen Hahm Design addresses this gap by integrating computational design, robotic fabrication, and augmented reality into construction workflows.

The studio’s Steampunk Pavilion, presented at the Tallinn Architecture Biennale, employed steam-bent timber elements assembled on site with guidance from augmented reality headsets, reducing reliance on conventional two-dimensional drawings. The project was not concerned with “smart” timber, but with adaptive fabrication—using digital tools to accommodate material variation during construction.

This approach is increasingly relevant. When materials vary, bend, or behave unpredictably, rigid documentation can become a liability. Designers must instead develop systems that absorb variation while maintaining structural integrity and spatial intent.

Designing for legibility, not novelty

The growing availability of programmable materials introduces a critical concern frequently noted in design and systems discourse: opacity. As materials respond, transform, or adapt, failures can become more difficult to diagnose, repair pathways less clear, and responsibility more diffuse. For designers working with behavioral materials, legibility becomes a central requirement. Clear stimulus–response relationships, modular systems, and transparent documentation are necessary if such materials are to move beyond experimental installations into durable, maintainable environments. From this perspective, the future of programmable matter is likely to hinge less on how much intelligence is embedded in materials than on how carefully behavior is governed—whether systems remain understandable, repairable, and ethically deployed over time.