Design culture has spent decades optimizing for novelty: faster tools, smarter systems, more autonomous outcomes. But as infrastructures age and environmental volatility intensifies, the limits of mastery-first design are increasingly visible. Buildings, platforms, and material systems rarely fail because they were insufficiently clever; they fail because they were insufficiently maintainable. Designing for maintenance reframes durability not as permanence, but as the capacity to endure breakdown, repair, and care over time.

Across architecture, materials research, and community-led practice, a quieter design ethic is emerging—one that treats upkeep as a primary condition rather than a postscript. This approach resists speculative solutionism and instead foregrounds stewardship, repair cultures, and systems designed to fail gracefully.

Maintenance as a Primary Design Condition

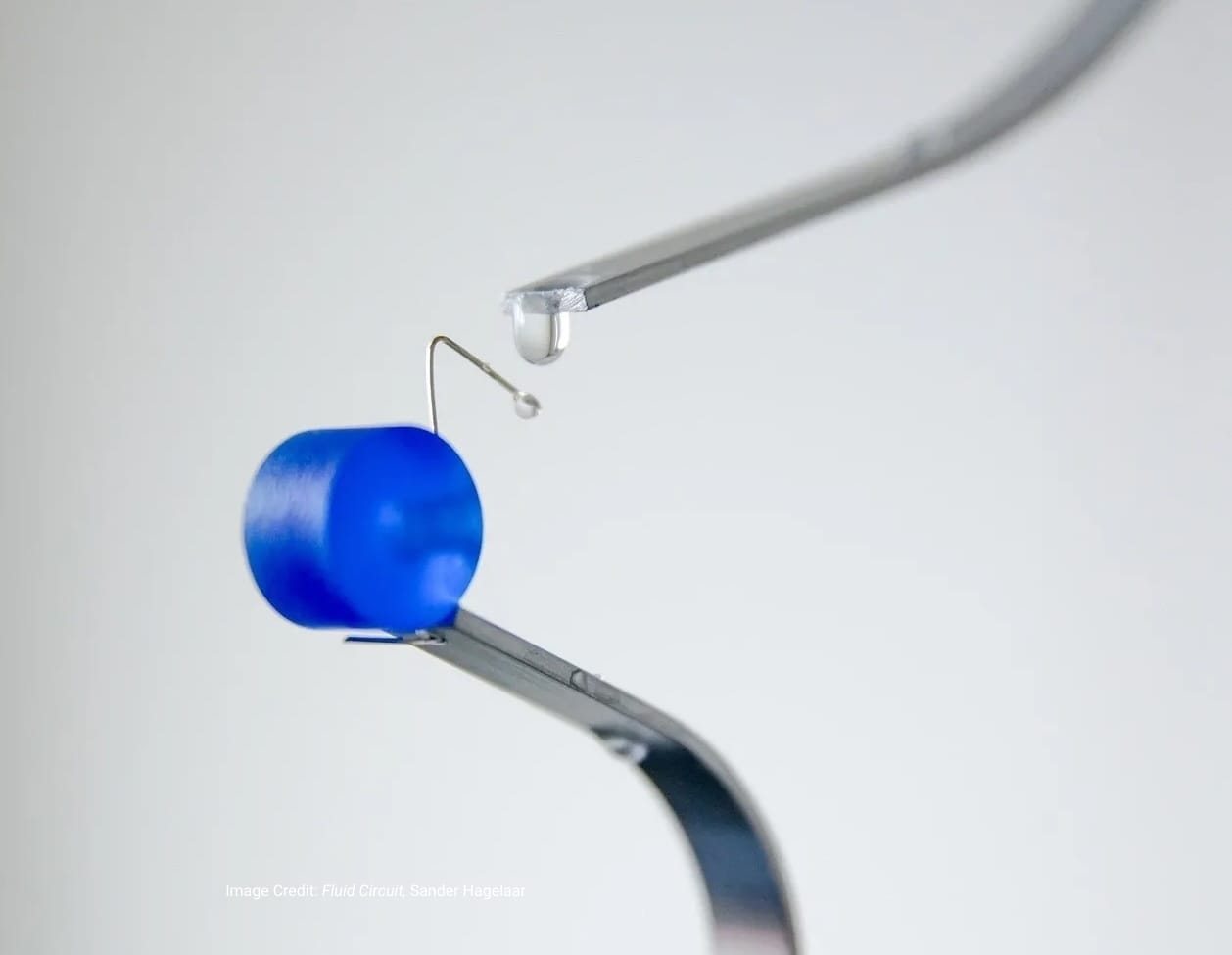

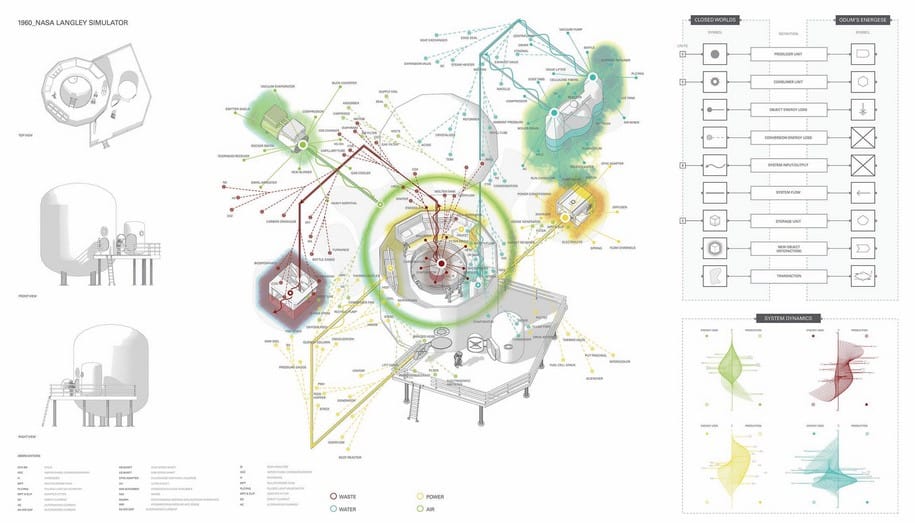

Maintenance has long been treated as an operational concern, external to the design act itself. Yet research-driven practices are increasingly exposing how maintenance is inseparable from form, material choice, and system logic. Architect and researcher Lydia Kallipoliti has been central to this reframing. Through projects such as Closed World and her broader scholarship on material ecologies, Kallipoliti examines closed-loop systems not as seamless technological fixes, but as inherently leaky, contingent constructs. Her work demonstrates that circular material systems demand constant intervention: monitoring material fatigue, recalibrating flows, and managing inevitable loss.

This perspective matters because it destabilizes the myth of self-sustaining systems. Closed loops do not eliminate maintenance; they intensify it. Designing with recycled or hybrid materials introduces variability that must be anticipated, not engineered away. For designers, this shifts the goal from perfect control to informed custodianship—understanding how materials age, deform, and require care. Maintenance, in this sense, becomes a design parameter that shapes spatial logic and material expression. Systems are legible rather than hidden. Interfaces expose wear rather than conceal it. The result is architecture and infrastructure that communicates its own vulnerability—and, crucially, how it can be sustained.

Long-Term Stewardship vs. Speculative Solutionism

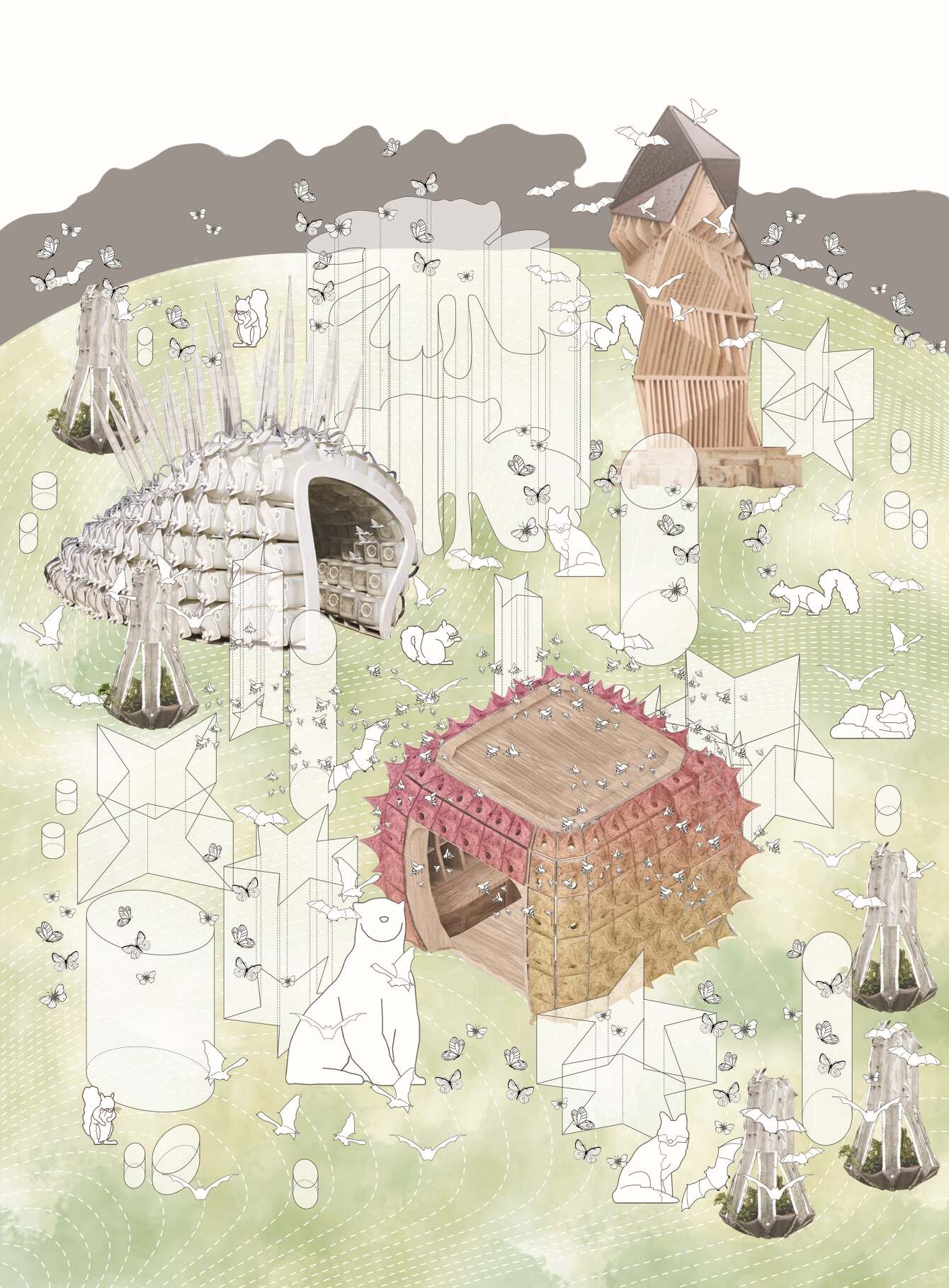

Speculative design has played a valuable role in expanding the imagination of what systems could be. But when speculation hardens into solutionism, it often prioritizes dramatic intervention over lived continuity. Community-centered practices offer a counterpoint. The UK-based collective Assemble is frequently cited for its emphasis on process over product. Projects such as the Granby Four Streets regeneration in Liverpool were not conceived as finished solutions but as frameworks for ongoing repair. Assemble’s role was not to replace community knowledge with professional authority, but to scaffold conditions under which residents could continue to adapt, fix, and maintain their environment.

What distinguishes this approach is its temporal logic. Success is not measured at completion but years later, through occupancy, modification, and care. Materials are chosen for accessibility rather than novelty. Construction methods favor techniques that can be relearned and repeated by non-specialists. Maintenance is social as much as technical. This model exposes a blind spot in much speculative work: systems designed without clear stewards tend to externalize responsibility. When maintenance is someone else’s problem, failure becomes more likely. Assemble’s work demonstrates that durability emerges from shared ownership and embedded repair cultures, not from optimization alone.

Designing Systems That Endure Breakdown and Repair

If maintenance is inevitable, then breakdown must be treated as a design scenario rather than an exception. Few architectural programs embody this logic as consistently as Rural Studio, the long-running design-build initiative based in Alabama. Operating in contexts of limited resources, Rural Studio designs buildings that anticipate wear, modification, and local repair. Their projects are intentionally over-documented and materially straightforward, enabling residents to maintain structures long after the designers have left. The architecture does not assume stable funding streams or specialized maintenance crews; it assumes improvisation.

This orientation toward continuity through care produces a different aesthetic and technical outcome. Details are robust rather than delicate. Systems are redundant rather than optimized to the edge. Materials weather visibly, making deterioration legible rather than catastrophic. In doing so, Rural Studio challenges the notion that resilience requires advanced technology. Often, it requires humility about what can realistically be sustained. For those working in digital or hybrid systems, the lesson translates directly. Platforms and tools that assume uninterrupted uptime or ideal user behavior tend to fracture under real-world conditions. Designing for maintenance means accounting for partial failure, degraded performance, and user-driven repair—whether that repair is technical, social, or organizational.

From Mastery to Care

Designing for maintenance is not anti-innovation; it is anti-amnesia. It recognizes that every system persists beyond its launch moment and that endurance is shaped less by brilliance than by care. Closed-loop materials, community-led repair, and design-build stewardship all point toward a shared conclusion: continuity is produced through ongoing attention.

As climate instability, resource constraints, and infrastructural fragility become baseline conditions, the most relevant design intelligence may lie not in predictive mastery but in adaptive maintenance. Systems that acknowledge their own fragility—while making repair possible—are better equipped to survive the long arc of use. In this framing, maintenance is not a compromise. It is a form of authorship that unfolds over time, shared among designers, users, and caretakers alike.