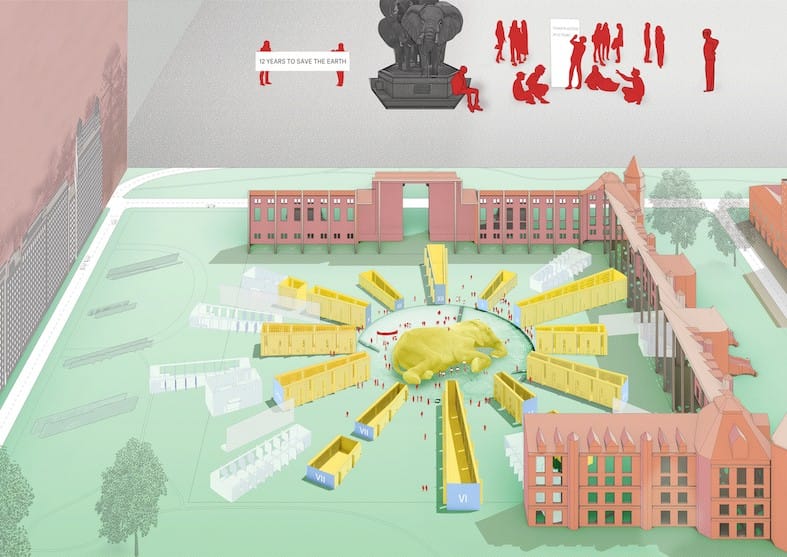

The rise of generative AI has produced an explosion of synthetic imagery, from near-photorealistic portraits to speculative design renderings. This is not breaking news. Nonetheless, as these systems flood culture with machine-made visuals, the question of intellectual property has moved from theoretical to urgent: who owns the image? The current debate continues to unfold across four interlinked arenas—copyrightability, training data rights, legal enforcement, and policy response—each exposing the fault lines between creative labor, corporate power, and algorithmic production.

Copyrightability: The Human Authorship Barrier

Copyright law has historically rested on the principle of human creativity. In the United States, the Copyright Office has made it clear that purely AI-generated works are not eligible for copyright protection. If an image is produced entirely by a system like Midjourney or DALL·E, based solely on a user’s text prompt, it cannot be copyrighted—meaning others may freely use it. Neither the model developer nor the individual user is considered the author. Yet the boundary is less clear when humans exert meaningful creative control. When a designer iteratively refines prompts, edits outputs, or integrates AI-generated fragments into a larger composition, some copyright protection may apply. Recent guidance from the U.S. Copyright Office suggests that such hybrid works can be registered, but only the human contributions—not the underlying AI elements—are covered.

Other jurisdictions are experimenting with different approaches. The United Kingdom’s Copyright, Designs and Patents Act recognizes “computer-generated works,” assigning authorship to the person who makes the arrangements for their creation. Meanwhile, a Beijing court recently upheld copyright protection for an AI-generated image, highlighting how global interpretations diverge. The underlying issue is conceptual: should originality require a human mind, or can human-directed machine outputs cross the threshold of creative expression? Until a consensus emerges, copyrightability will remain a contested and highly contextual determination.

Training Data Rights: Fair Use or Mass Infringement?

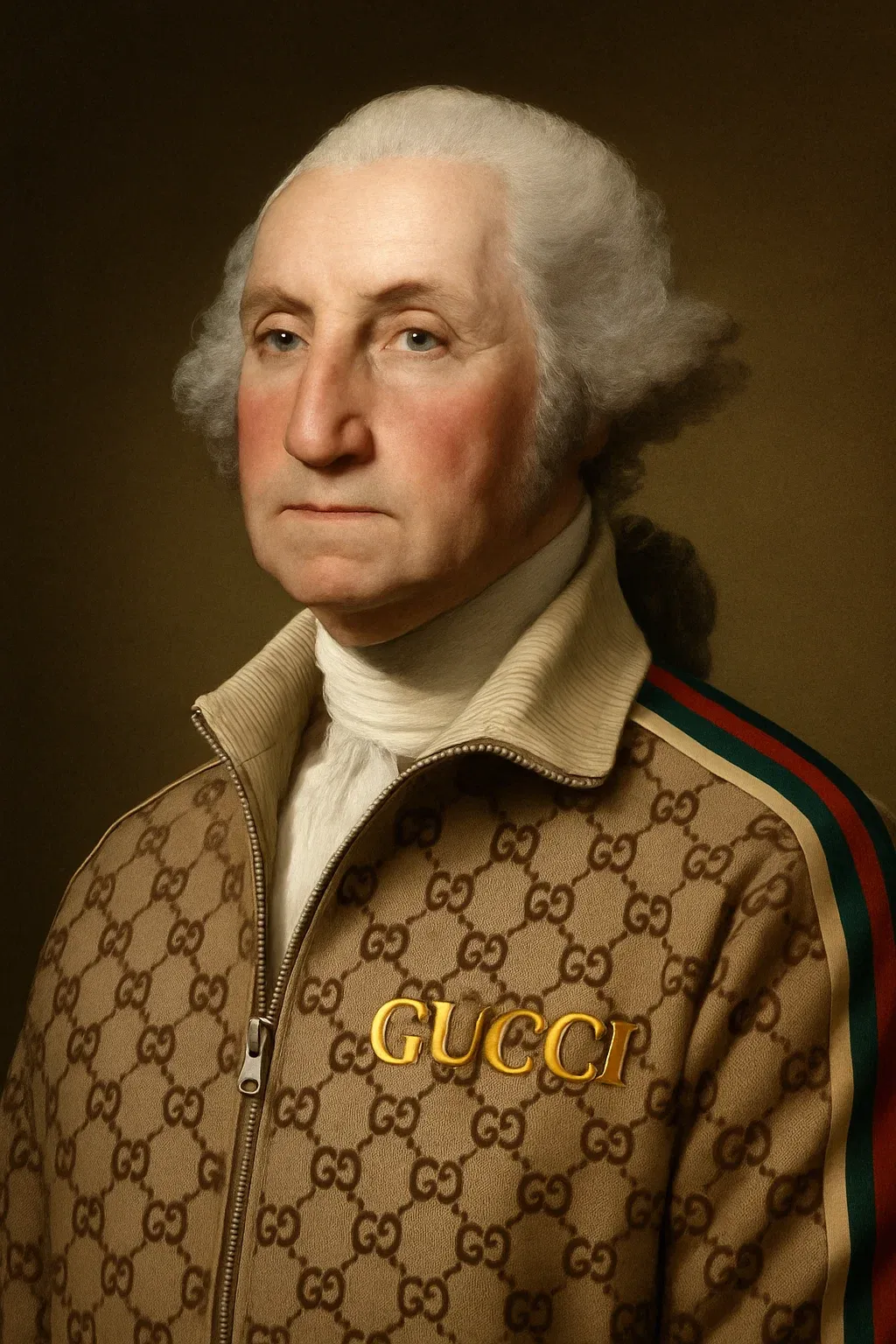

The debate extends beyond outputs to the inputs that make generative systems possible. Training data for image models often includes billions of images scraped from the internet, many of them copyrighted. Developers argue that using these datasets should qualify as “fair use”—a transformative practice akin to how humans learn by exposure to existing works. Rights holders counter that mass scraping without consent amounts to systematic infringement. This tension has already sparked high-profile litigation. Getty Images sued Stability AI in the U.K. for allegedly copying millions of photographs to train Stable Diffusion without authorization, with the case set for trial in 2025. In the United States, Disney and Universal filed lawsuits against Midjourney in 2025, alleging that its training and outputs drew on copyrighted characters such as Darth Vader and Elsa. A coalition of artists has also brought suits against Stability AI and Midjourney, claiming their works were misappropriated to generate derivative images; while some claims were dismissed, others—such as direct infringement—are still moving forward.

Beyond the courtroom, the dispute raises ethical questions. Many artists see generative AI as a form of uncompensated labor extraction—models are effectively trained on years of creative effort without acknowledgment or licensing. On the other side, developers warn that restricting training data too tightly could stifle innovation and limit the capabilities of AI systems.

Legal Enforcement: A Growing Patchwork

As these disputes unfold, courts worldwide are establishing precedents that could shape the future of creative AI. The Getty Images case, scheduled for trial in the U.K. in summer 2025, may clarify how courts view the unlicensed use of copyrighted works in training datasets. In the United States, Disney and Universal’s lawsuit against Midjourney could set important standards for how character likenesses and fictional universes are protected against algorithmic replication.

Smaller but significant cases are also chipping away at the issue. In 2023, a U.S. federal judge dismissed parts of the artists’ lawsuit against Stability AI but allowed claims of direct infringement to proceed. Authors and publishers, including the New York Times, have filed suits over AI training on text, showing that the conflict is not limited to visual media. The result is a fragmented legal environment where outcomes vary across jurisdictions and contexts. For creators and companies working globally, this patchwork complicates risk management and makes liability difficult to predict.

Policy Response: Transparency, Disclosure, and Labeling

Policymakers are beginning to step in, but responses remain uneven. In the United States, the Generative AI Copyright Disclosure Act, introduced in 2024, would require developers to disclose whether copyrighted materials were used in training datasets at least 30 days before releasing a model. The act stops short of banning such use but seeks to bring transparency to a process that has largely been opaque. The U.S. Copyright Office has also released a series of reports in 2025—one addressing the copyrightability of AI-generated outputs, and another examining the legality of training practices.

The European Union has taken a more regulatory stance through the AI Act, which obliges providers to indicate whether copyrighted works were used in training and to label AI-generated outputs. These provisions build on the EU’s framework for text-and-data mining (TDM) exceptions, which allow the use of copyrighted material for machine learning unless rights holders explicitly opt out. Elsewhere, approaches remain less developed. The U.K. is pursuing a code of practice on AI and copyright through its Intellectual Property Office, while China has signaled more openness by recognizing copyright in some AI-generated works through recent court decisions. Each approach reflects distinct cultural and legal priorities, suggesting that global harmonization is unlikely in the near term.

The Unfinished Framework

The question of who owns the image in generative AI is not just a technical legal matter—it’s a cultural and economic struggle over how creativity is valued in an age of algorithmic production. Current law leans heavily toward protecting human authorship, while AI-only outputs remain ineligible for copyright protection. At the same time, the battle over training data pits notions of fair use against the rights of creators whose work underpins these systems. For now, the landscape is defined by uncertainty. Courts are testing arguments, lawmakers are drafting disclosure requirements, and artists are demanding stronger protections. The eventual framework will likely blend legal standards, industry practices, and technical safeguards such as provenance metadata or opt-out systems for training data.

What remains clear is that the stakes are high: the outcome will shape not only the economics of creative labor but also the cultural legitimacy of machine-made art. The fight over generative AI and intellectual property is less about ownership of any single image and more about defining the contours of authorship in a computational age.