As artificial intelligence saturates design discourse, computation is still too often framed as something that happens inside software: code executing on silicon, data processed by remote servers, intelligence abstracted from matter. Yet a parallel lineage in design research challenges that assumption. Across architecture, materials science, and fabrication, designers are working with materials that sense, respond, adapt, and reorganize—performing forms of computation without electronics, sensors, or centralized control. This shift reframes intelligence not as an overlay added through software, but as something embedded in physical behavior itself. Under the right conditions, materials can compute.

Material behavior as distributed computation

At the heart of this approach is a consequential proposition: computation does not have to be confined to software or electronic control systems. In material-centered design research, behavior can be produced through distributed physical processes, where transformation is driven by how materials are structured rather than by step-by-step digital instruction. Instead of executing code, these systems rely on geometry, composition, and internal forces to produce predictable responses. Behavior emerges through interaction, not command.

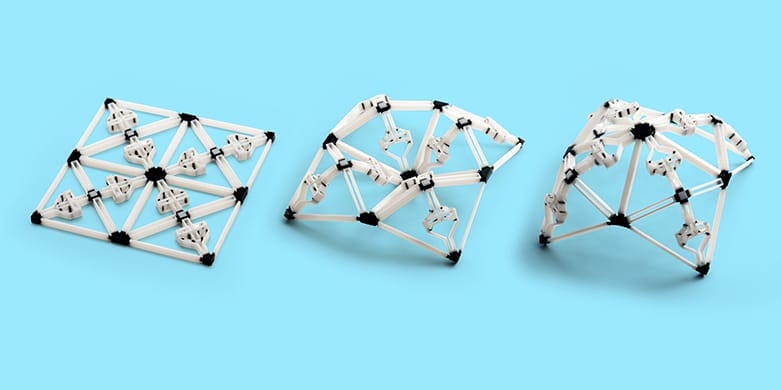

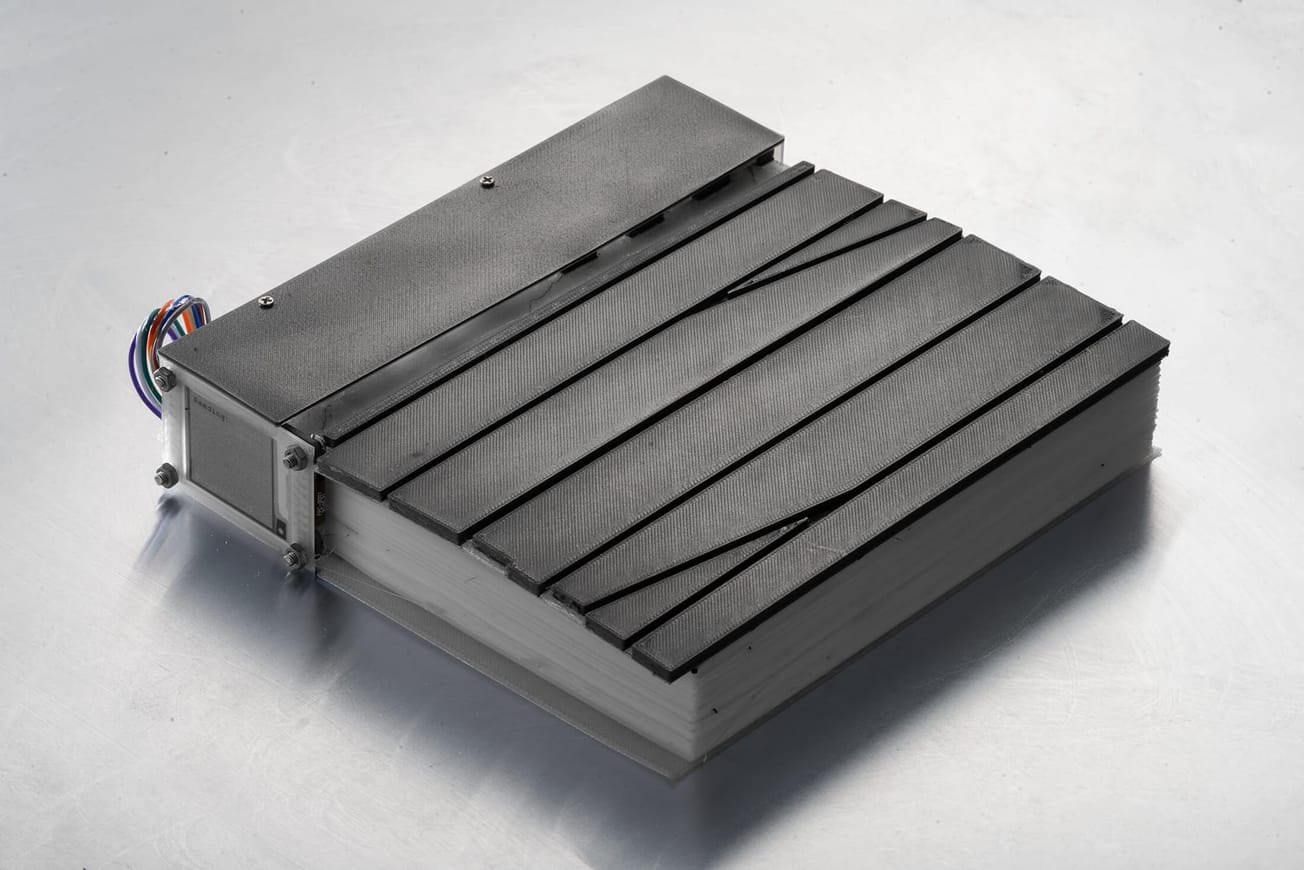

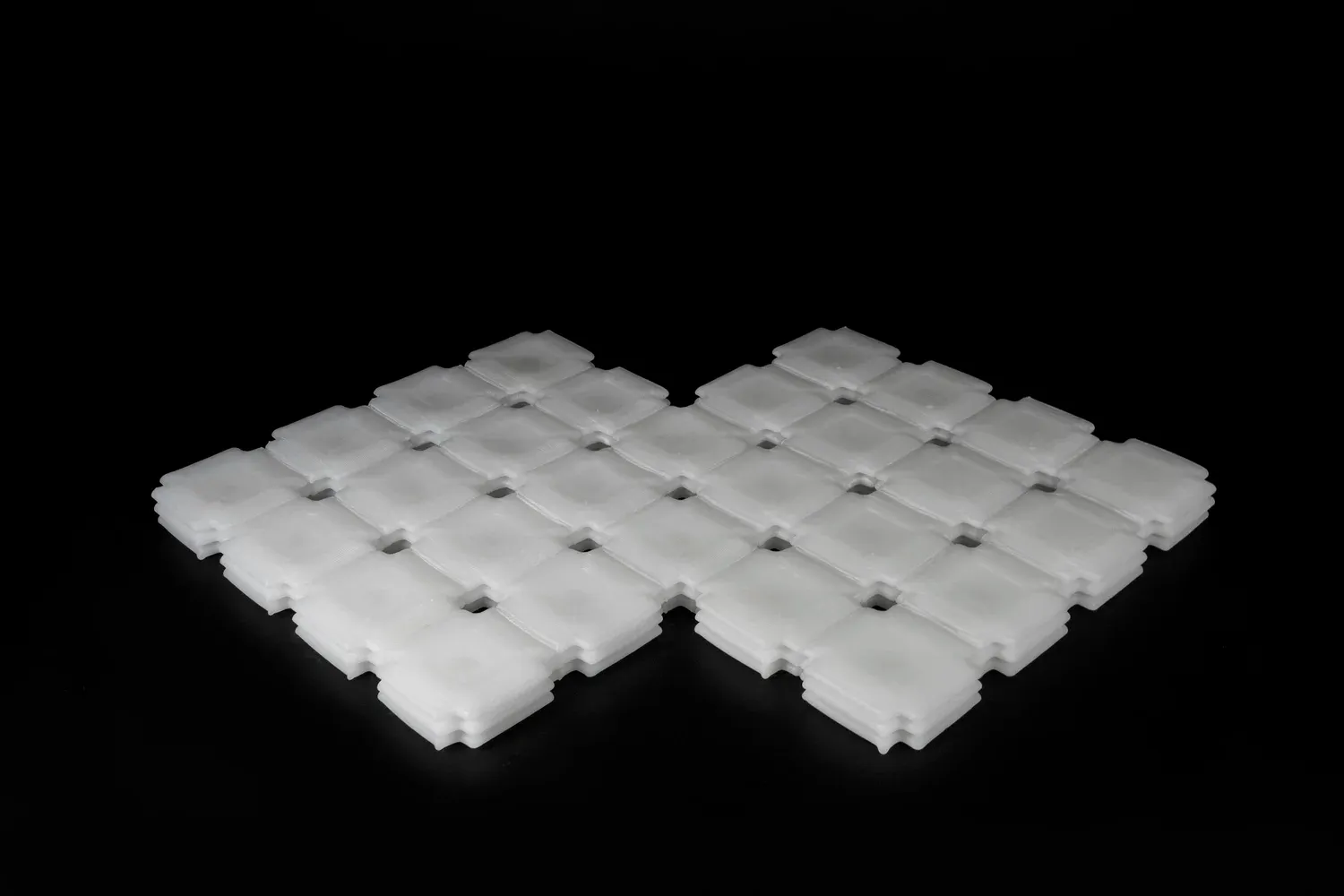

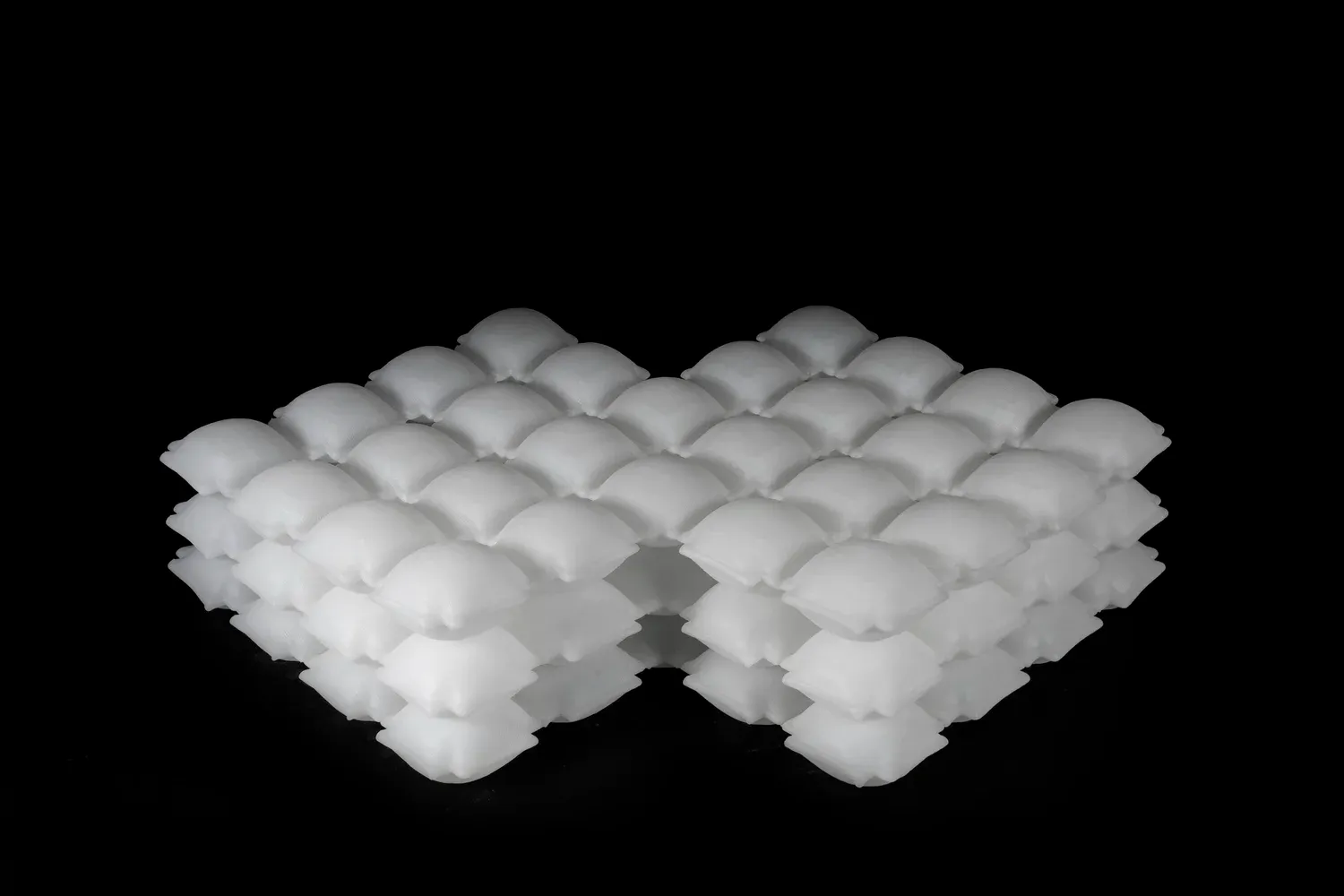

The work of the MIT Self-Assembly Lab, founded and led by Skylar Tibbits, exemplifies this logic. The lab investigates self-assembly and programmable materials—systems in which components can autonomously fold, aggregate, or change shape when exposed to external stimuli. Across projects involving self-folding sheets and shape-changing composites, “programming” is achieved through material gradients, residual stresses, and environmental triggers such as heat or moisture, rather than through sensors or active control. Self-assembly is framed as a process driven by local interactions, where order emerges without centralized coordination.

What is at stake in this work is less technological novelty than a reallocation of control. Rather than relying on external computation to determine behavior in real time, decision-making is embedded into the material system itself. The material does not execute instructions in the conventional computational sense; it responds to conditions it has been designed to register. Folding, bending, swelling, or aggregation function as physically encoded responses, unfolding in parallel across a system and reducing reliance on continuous energy input or mechanical mediation. This approach aligns with research in morphogenesis and systems biology, where complex form arises from local interactions rather than top-down specification. Designers working with material computation similarly define constraints, thresholds, and material tendencies, allowing outcomes to emerge through interaction with environmental forces. Intelligence, in this framing, is not concentrated in an algorithm or controller, but distributed across a system’s material organization.

Environmental responsiveness vs. digital control

Material computation becomes especially legible when contrasted with digitally controlled responsiveness. Many smart buildings, adaptive façades, and responsive products rely on networks of sensors, actuators, and control software—technical layers that require continuous energy supply, calibration, and maintenance. Environmental data is captured, processed, and translated into action through centralized or semi-centralized control logic.

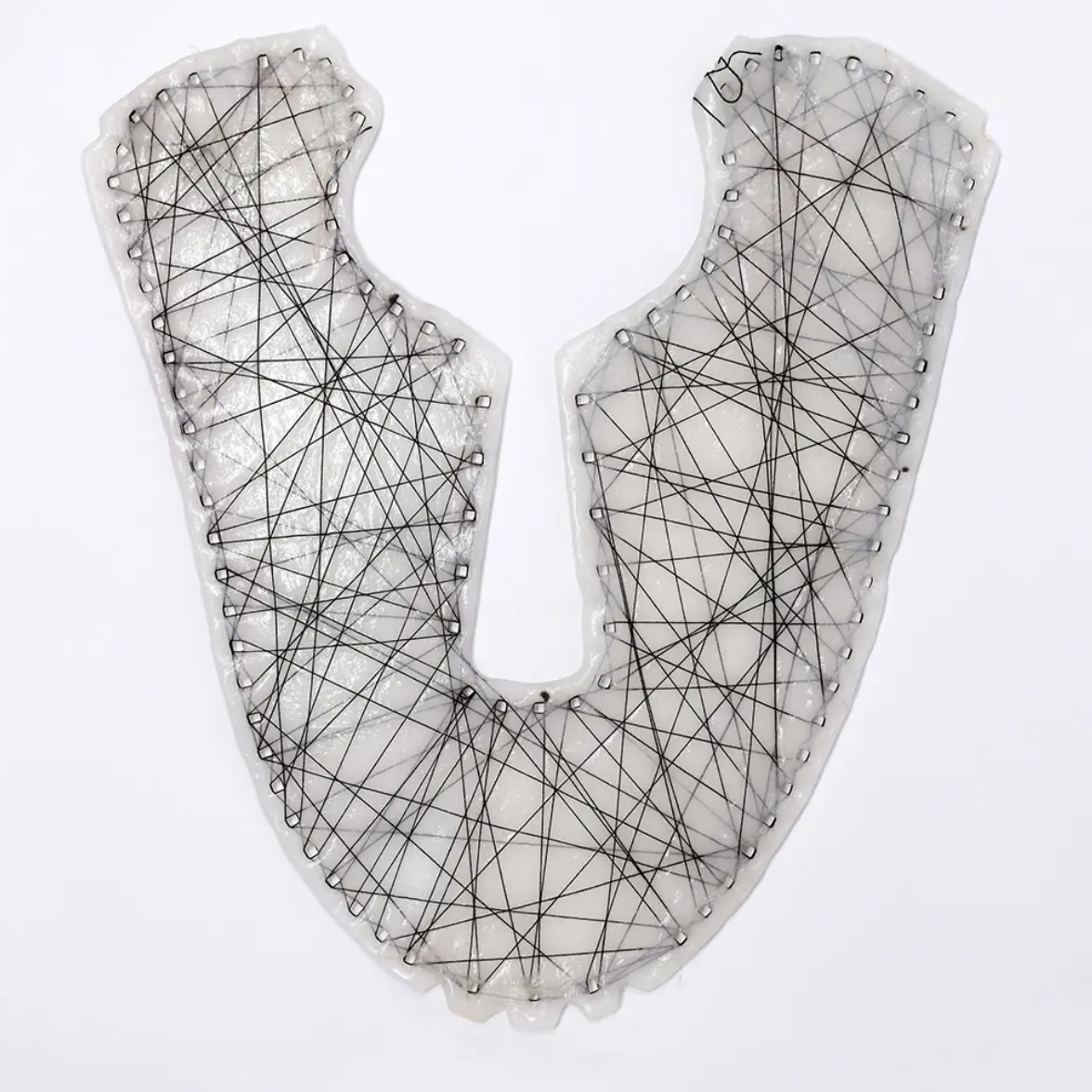

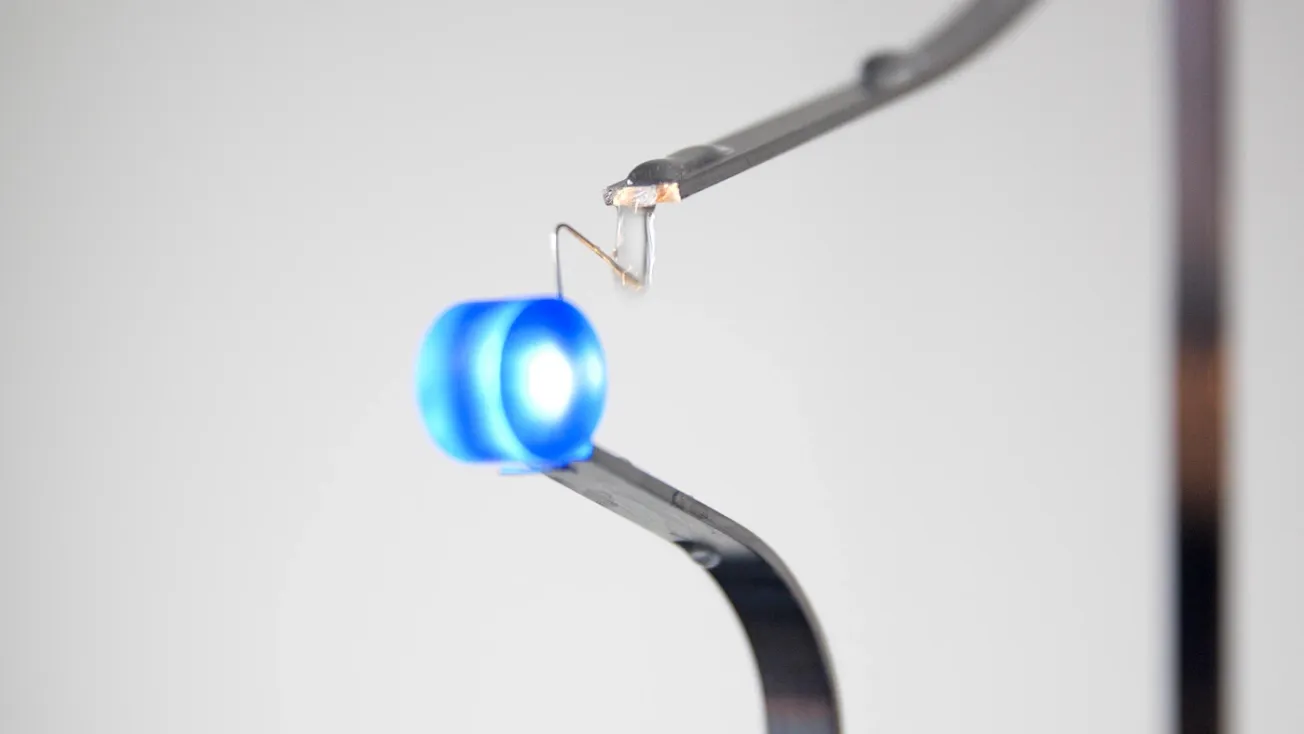

Materially responsive systems operate differently. Certain materials respond directly to environmental conditions through their physical properties. Hygroscopic wood expands or contracts with humidity. Bimetallic strips bend predictably with temperature variation. Fiber-based composites can stiffen, relax, or reorient under load depending on internal structure. These responses occur as continuous physical processes rather than discrete computational decisions, without relying on data capture, digital thresholds, or external controllers.

Research led by Achim Menges at the Institute for Computational Design (ICD), University of Stuttgart, has been particularly influential in advancing this approach within architecture. Through work on wood and fiber composite systems, Menges and his collaborators have shown how material behavior itself can act as a design driver, enabling structures to adapt to environmental conditions without motors, sensors, or mechanical actuation. Performance emerges from how materials are organized and fabricated, rather than from real-time digital control.

The implications extend beyond technical performance. Digitally controlled systems embed governance into software and infrastructure through decisions about which data matters, how thresholds are defined, and which responses are authorized. Materially responsive systems, by contrast, operate through embedded physical logic that is legible at the scale of the material itself and difficult to modify remotely. While they trade fine-grained precision for coarser forms of adaptation, they often favor robustness, continuity, and long-term stability—qualities increasingly relevant for designers concerned with autonomy, transparency, and durability.

Sustainability implications of non-electronic intelligence

The environmental stakes of material computation are difficult to ignore. As AI-driven systems expand, so does their dependence on energy-intensive infrastructure, including data centers, sensor networks, rare earth materials, and short-lived electronic components. In this model, intelligence is tightly coupled to extractive supply chains and ongoing energy consumption.

Materially based forms of intelligence offer an alternative. Systems that rely on physical behavior rather than electronics can operate without embedded sensors, firmware updates, or network connectivity, often drawing energy directly from environmental conditions such as humidity, temperature, gravity, or load. Because behavior is governed by material properties rather than software, degradation typically occurs through wear or environmental exposure rather than sudden technical failure, shifting maintenance toward material stewardship. At building and urban scales, this enables different design strategies: adaptive shading elements that respond to climate without motors, structural components that redistribute stress through geometry, and infrastructure designed to accommodate seasonal variation passively rather than through constant optimization.

Institutions such as the Institute for Advanced Architecture of Catalonia (IAAC) have been instrumental in translating these ideas into applied research and education. IAAC’s work on bio-based materials, climate-responsive systems, and low-energy fabrication positions material intelligence as a practical design strategy rather than a speculative abstraction. Here, computation is not removed from material reality but embedded within it, aligning performance with ecological constraint. This shift does not imply a rejection of digital tools. Simulation, modeling, and digital fabrication remain essential for designing material systems whose behavior is complex and nonlinear. The distinction lies in where intelligence ultimately operates: digital tools define conditions and parameters, while the resolution of behavior is delegated to material systems rather than continuously managed through software.

Designing with behavior, not control

As materially responsive systems gain traction, they prompt a reassessment of long-standing assumptions about authorship and control. When behavior emerges through interaction rather than direct instruction, the designer’s role shifts from specifying final form to shaping conditions and tendencies. Performance is evaluated less by precision than by adaptability.

As ecological pressures intensify and technological systems grow more opaque, interest in intelligence that is visible, local, and materially grounded continues to grow. Materially responsive systems do not promise total control. Instead, they demonstrate how design can operate within uncertainty. The most consequential forms of design intelligence may not run entirely on software, but through material processes that swell, bend, crack, and recover—quietly computing in plain sight.