Mycelium—the sprawling, root-like network of fungi—has been hyped as the next big thing in sustainable materials for a number of years. Designers are already using it to grow biodegradable packaging, leather alternatives, even self-healing walls. But one application has been largely overlooked: ink.

That’s changing fast. A new wave of biohackers, designers, and researchers is hacking fungi to grow their own ink, replacing petroleum-based pigments with fully compostable, shape-shifting, and self-repairing alternatives. And the best part? You can grow it yourself.

Why Hack Your Own Ink?

Ink seems harmless, but it’s a hidden environmental nightmare. Most commercial inks contain petroleum-based pigments, chemical solvents, and microplastics, making them difficult—if not impossible—to recycle. Even “eco-friendly” inks often rely on synthetic stabilizers. Mycelium ink rewrites the rules. It’s fully biodegradable, grown rather than extracted, and in some cases, even self-healing. Some formulations can repair cracks or damage over time. Others react to heat, moisture, and even UV light.

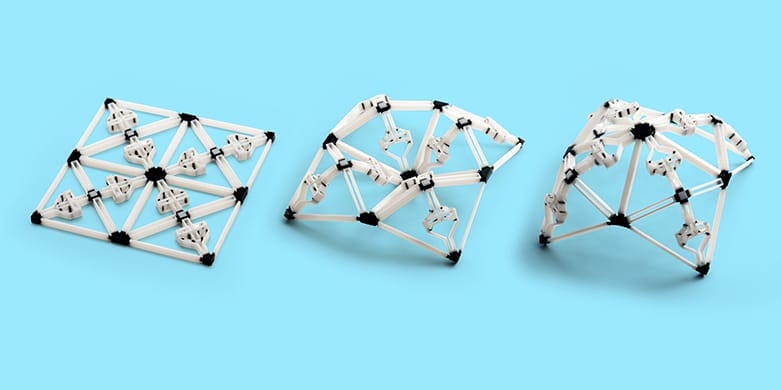

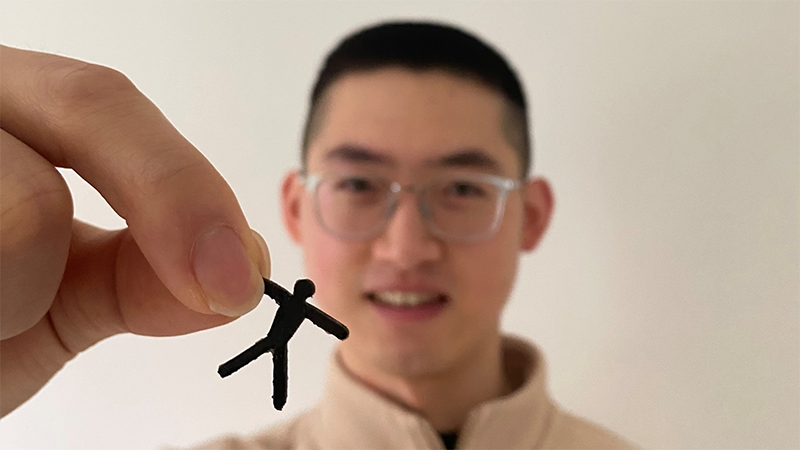

Credit: Gantenbein, S., Colucci, E., Käch, J. et al. Three-dimensional printing of mycelium hydrogels into living complex materials. Nat. Mater. 22, 128–134 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41563-022-01429-5

Researchers at ETH Zurich’s Complex Materials Group have even developed a 3D-printable mycelium ink that forms a soft yet resilient material capable of repairing itself when damaged. Led by researchers Silvan Gantenbein, Emanuele Colucci, Julian Käch, Etienne Trachsel, Fergal B. Coulter, Patrick A.Rühs, Kunal Masania, and André R. Studart. Their 3D-printable mycelium ink is designed not just as a pigment but as a functional living material. It forms soft yet resilient coatings that resemble leather, repairs itself when damaged, and remains fully biodegradable. In early tests, their ink has been used for robotic skins, waterproof coatings, and experimental architecture—all powered by fungal biology.

Researchers at the Forefront of Mycelium Ink

ETH Zurich’s Complex Materials Group isn’t alone in pushing the boundaries of what mycelium ink can do. At MIT’s Mediated Matter Lab, researchers are investigating biologically inspired fabrication techniques, including bio-inks and responsive materials, to explore the relationship between natural and synthetic structures in architecture. Meanwhile, bioartists and experimental designers worldwide are working with fungal-based pigments and organic printing techniques to create sustainable, evolving artworks.

While ETH Zurich is bringing mycelium ink into the world of functional materials and 3D printing, bioartists are using it to explore the possibilities of dynamic, living prints. Across labs, studios, and underground biohacker spaces, the same question is being asked: What if the ink wasn’t just something we applied to a surface but something that grew, evolved, and even repaired itself?

Credit: Gantenbein, S., Colucci, E., Käch, J. et al. Three-dimensional printing of mycelium hydrogels into living complex materials. Nat. Mater. 22, 128–134 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41563-022-01429-5

How to Grow Your Own Mycelium Ink

You don’t need a bioengineering degree to get started. With a few basic materials and some patience, you can cultivate fungal pigments in your own home lab.

Step 1: Choose Your Fungus

Different fungi produce different colors and textures. Some of the best strains for ink-making:

- Ganoderma lucidum (Reishi) – Reddish-brown, rich and earthy.

- Pestalotiopsis microspora – Known for breaking down plastics with deep black hues.

- Schizophyllum commune – Great for creating spore-based prints.

You can order spores from mycology suppliers or harvest them from rotting wood in the wild—just be sure to sterilize them before culturing.

Step 2: Grow the Mycelium

This part is like setting up a homebrew operation but for ink.

- Prepare a growth medium: The easiest option is agar plates, but you can also use oatmeal and water or potato dextrose broth.

- Inoculate the medium: Using a sterile scalpel or syringe, introduce your fungal spores.

- Incubate: Keep it in a dark, warm place (70–80°F). Within days, white, web-like mycelium will start spreading.

Wait a week or two, and you’ll have enough fungal biomass to start extracting pigments.

Step 3: Extract the Pigment

Once your mycelium is fully grown, it’s time to turn it into ink.

- Harvest the mycelium: Cut or scrape it from the growth medium.

- Break it down: Blend with warm water or ethanol to extract the pigments.

- Filter the liquid: Strain through cheesecloth to remove solid bits.

- Concentrate the ink: Reduce over low heat until it reaches the consistency of traditional ink.

Some fungi change color when exposed to oxygen or UV light. Others need a chemical tweak—a little acid or base—to bring out their full spectrum.

Step 4: Stabilize and Print

Because mycelium ink is organic, it’s not as predictable as store-bought ink. It can dry out, morph, or even continue to grow if left unchecked. To stabilize it, add gum arabic or natural binders to improve consistency. Store it in airtight glass containers to prevent contamination.

Test it on different surfaces—fungal ink interacts with paper, wood, and fabric in unexpected ways. You can use it in brushes, pens, and even screen-printing, or 3D-print it onto textiles and biodegradable plastics. If you’re feeling ambitious, feed the spores nutrients post-printing, and watch as your designs grow over time.

Beyond Ink: Printing With Living Matter

The real power of mycelium ink isn’t just in creating an environmentally friendly pigment—it’s in redefining what ink itself can be. Biofabricators are already exploring how fungal inks can be used to form self-growing structures, inspired by the way slime molds naturally find the most efficient pathways between points. Some researchers envision using mycelium ink in 3D printing to replace plastic-based filaments, creating biodegradable coatings and packaging materials that naturally decompose when no longer needed. Others are looking beyond aesthetics, developing fungal-based paints and coatings that can actively filter toxins from the air or absorb carbon dioxide. The ultimate vision isn’t just to replace synthetic materials but to move toward an entirely new paradigm—one where the things we print don’t just sit passively on a page but actively respond, change, and even repair themselves over time. Instead of treating ink as something static, mycelium ink challenges us to think of it as something living, something that interacts with its surroundings in ways we’re only beginning to understand.

The Future of DIY Mycelium Ink

For now, growing mycelium ink is still a fringe experiment. But as the world moves toward biodegradable, regenerative materials, it’s only a matter of time before fungal-based printing hits the mainstream.

This isn’t just about ink. It’s about redefining what materials can do—from something that sits passively on a page to something that grows, evolves, and disappears when it’s no longer needed. If the future of fabrication is biological, then the future of printing is fungal. And the best way to get ahead of it? Start growing.

Check out the Future of Materials for the latest developments in Mycelium Ink research!