The myth that technology will inevitably deliver a better future has long dictated the direction of creative industries. Critical designers have spent decades dismantling that belief, challenging the notion of innovation as an unqualified good. Their work cuts through the glossy promises, exposing the contradictions embedded in our collective digital dreams. Instead of designing for convenience, they are designing to confront the status quo, to question political constructs, and expose deeply embedded social inequities.

Critical design, once defined in the early 2000s by Anthony Dunne and Fiona Raby, has evolved into a robust form of "world refusal," a deliberate rejection of the belief that technological progress is synonymous with human progress. This domain matters more than ever, with advances in artificial intelligence, biotechnology, and algorithmic governance. In doing so, critical design doesn’t just imagine alternative futures—it insists on interrogating the present.

Beyond Products: Provocations Against Progress

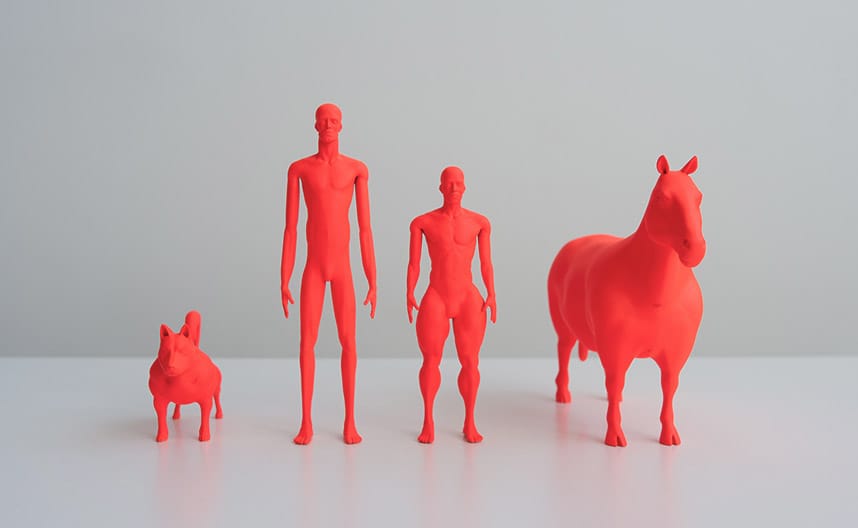

Dunne and Raby’s work remains foundational. Their projects, such as United Micro Kingdoms and Speculative Everything, illustrate futures that could easily tilt into dystopia. They demonstrated how design can be a political act; one predicated on problem seeking, speculating on a future to critique the present rather than design as a problem-solving tool for a commercial application.

A number of designers have extended this critical orientation, reframing design not as an enabler of consumer futures but as a tool for systemic exposure. James Auger, one of the most consistent voices in this evolving field, builds on Dunne and Raby’s speculative legacy by materializing ideological critiques. His work questions the presumed inevitability and desirability of “smart” technologies. Through provocative artifacts—devices that expose contradictions in automation, surveillance, and algorithmic logic—Auger demonstrates how design can act as a mirror, reflecting the assumptions that underpin our relationship with technology. He belongs here not simply as a disciple of the Dunne and Raby approach, but as a designer who has helped reframe critical design as an evolving, applied discourse.

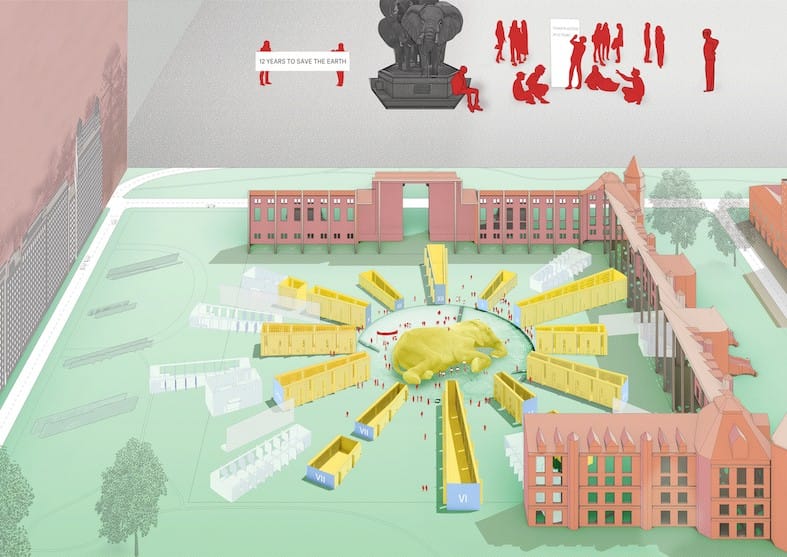

Superflux, the studio founded by Anab Jain and Jon Ardern, offers some of the most potent recent examples of critical design as world refusal. Projects like Mitigation of Shock immerse audiences in gritty near-futures shaped by climate collapse and technological inequality, while The Intersection explores coexistence amid networked crises. Rather than promising solutions, Superflux forces participants to grapple with adaptation and survival.

Other practitioners expand the critical lens beyond discrete objects, interrogating the deeper systems—social, biological, colonial—that scaffold our technological realities. Luiza Prado de O. Martins investigates reproductive technologies as vectors of control, drawing lines from colonialism to contemporary biopolitics. Her practice leverages poetic storytelling to surface how seemingly neutral systems perpetuate racialized, gendered oppression. These aren't speculative futures—they're the present, examined through a critical, decolonial lens.

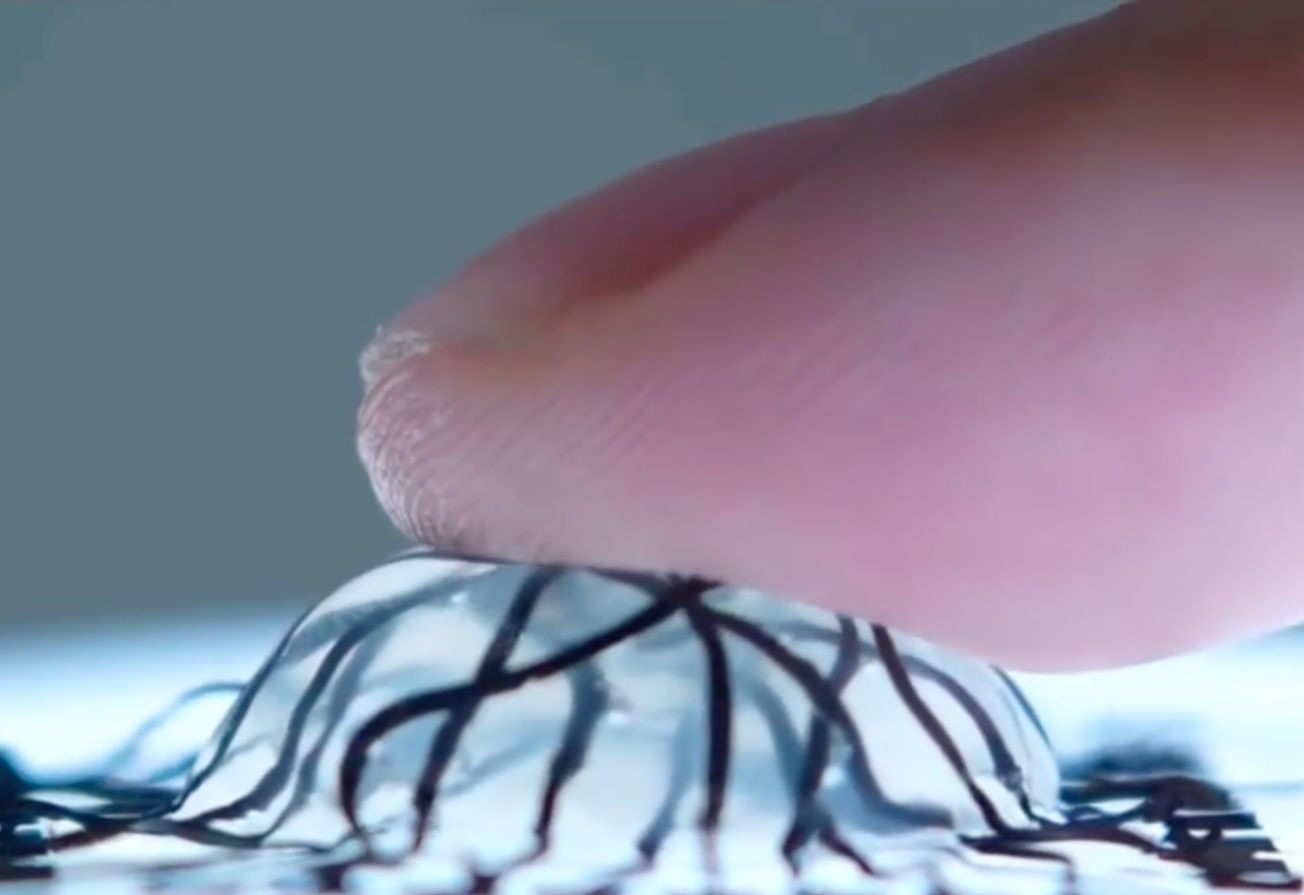

Where Prado engages systemic narratives, Natsai Audrey Chieza turns her focus to physical production systems. Her biofabrication work with microbial dyes and lab-grown textiles critiques the ecological violence of industrial design while offering living, responsive alternatives. In Mutupo, Chieza interrogates the biopolitical dimensions of biotechnology itself, tracing how Western science commodifies and circulates genomic data—specifically, the highly diverse gut microbiome profiles of the Hadza people of Tanzania. By reframing this dataset not as raw material but as a site of cultural and ecological entanglement, Chieza asks who benefits from “future-making” and at what cost. Biology, in her work, is not an aesthetic flourish but a contested collaborator, revealing sustainability as an ethical and political question, not just a material one.

Distributed Resistance: Critical Design Across Creative Domains

Not all critical design emerges from studios labeled as such. Increasingly, artists and cultural practitioners are embedding critical design methodologies into broader creative ecosystems—from ecological art to spatial justice. These practices refuse the neutral aesthetics of innovation and instead confront the social, political, and environmental systems that shape our world.

Mary Mattingly, for example, builds mobile, modular living systems that confront climate collapse not with techno-solutionism but with radical self-sufficiency. Projects like Waterpod and Swale establish floating habitats and public food forests in urban waterways, offering speculative but functional interventions into how we might live and share resources outside extractive systems. Her work asks what forms of life are possible when we untether ourselves from extractive infrastructures and imagine the city as a shared commons.

Torkwase Dyson navigates the intersection of Black spatial politics, architecture, and abstraction. Her geometric forms and sculptural environments draw from histories of movement, resistance, and environmental struggle—what she calls “Black compositional thought.” In works like Liquid A Place, Dyson constructs immersive installations that use sweeping arcs, heavy steel, and negative space to evoke both the impossibility and necessity of refuge in hostile environments. Rather than designing objects, Dyson designs conditions: for breathing, for remembering, for reorienting space around bodies historically excluded from its shaping.

Joey Holder’s sprawling, immersive installations evoke speculative ecosystems shaped by both biological and technological forces. By collapsing distinctions between the organic and synthetic, Holder critiques the techno-utopian fantasy of total control over nature.

Across these practices, design is not a product but a provocation. It is a means to rehearse new relations to land, labor, and each other—and to ask, again and again, not just how we build, but for whom, and why.

Beyond individuals, collectives like the Design Justice Network and the Feral Atlas Collective are architecting counter-infrastructures. The Design Justice Network centers marginalized voices to challenge who benefits from "innovative" design. The Feral Atlas Collective, led by anthropologist Anna Tsing, invites users to explore ecological disruptions without prescribing easy technological fixes, thereby resisting the dominant narratives of mastery and control.

Critical design does not offer a neat exit from our current crises. Instead, it insists on complexity, demanding that we sit with uncertainty, contradiction, and conflict. These designers are not building alternate utopias; they are cultivating spaces of friction, tension, and radical possibility—sites where different futures might take root. Refusal, in their hands, becomes not a retreat but a generative act: an opening toward futures we are only just beginning to imagine.