As cities expand, the survival of pollinators—bees, butterflies, moths, and other insects vital to global food systems—becomes increasingly precarious. Habitat loss, monocultural landscapes, and urban fragmentation have driven global declines in pollinator populations. Architecture has typically addressed this crisis through surface-level gestures, such as green façades or rooftop gardens. Wild Futures, a project by Infra-Architecture Lab, takes a different position. It treats pollinator survival as a central architectural challenge, asking how buildings themselves might function as ecological infrastructure.

Founded by Rafael Luna, the lab operates at the intersection of speculative design and research-driven prototyping. Developed in the context of the University of Technology Sydney, Wild Futures extends beyond a single prototype toward a broader question: what would it mean if the form, structure, and ornamentation of buildings were shaped by the needs of nonhuman species?

Pollinator Tectonics as Design Logic

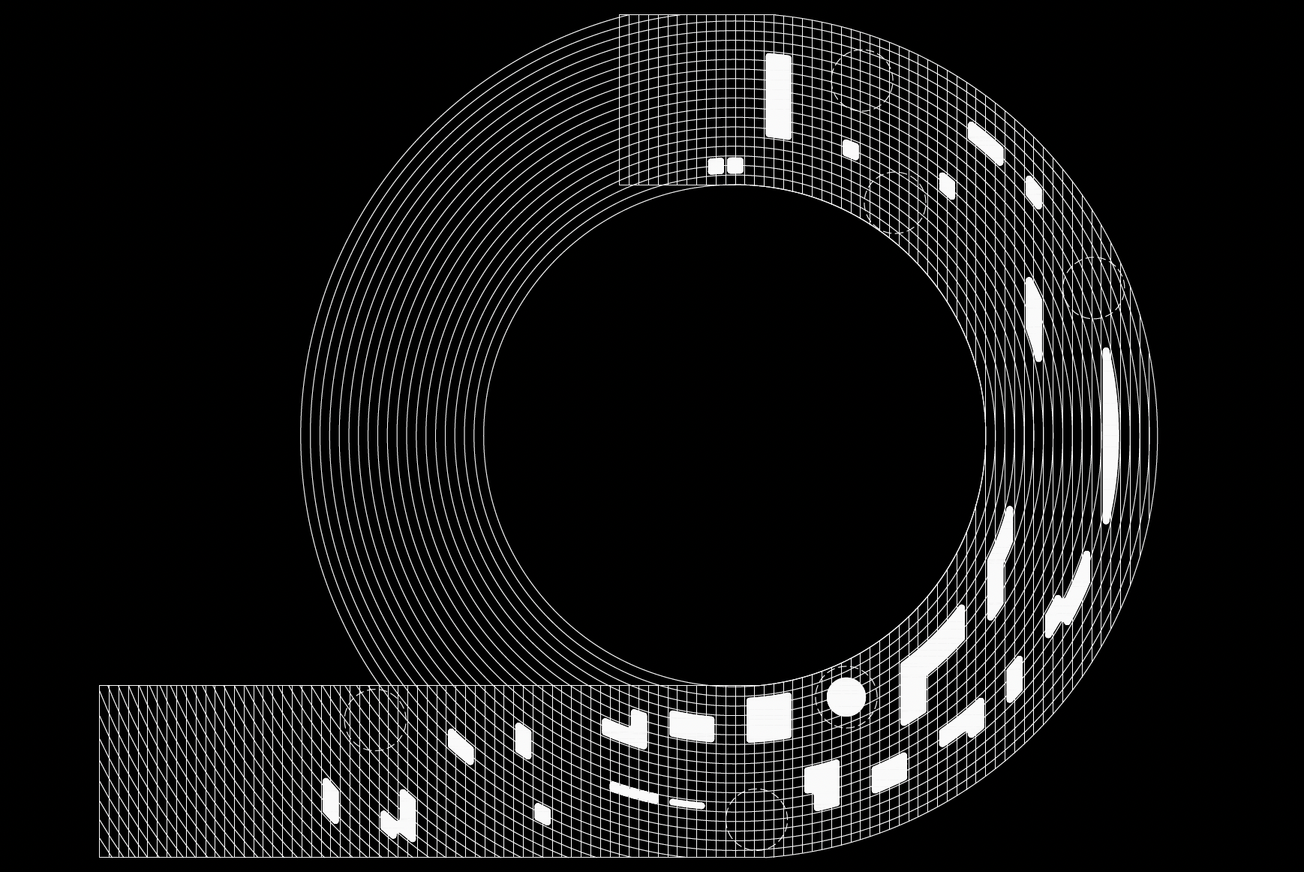

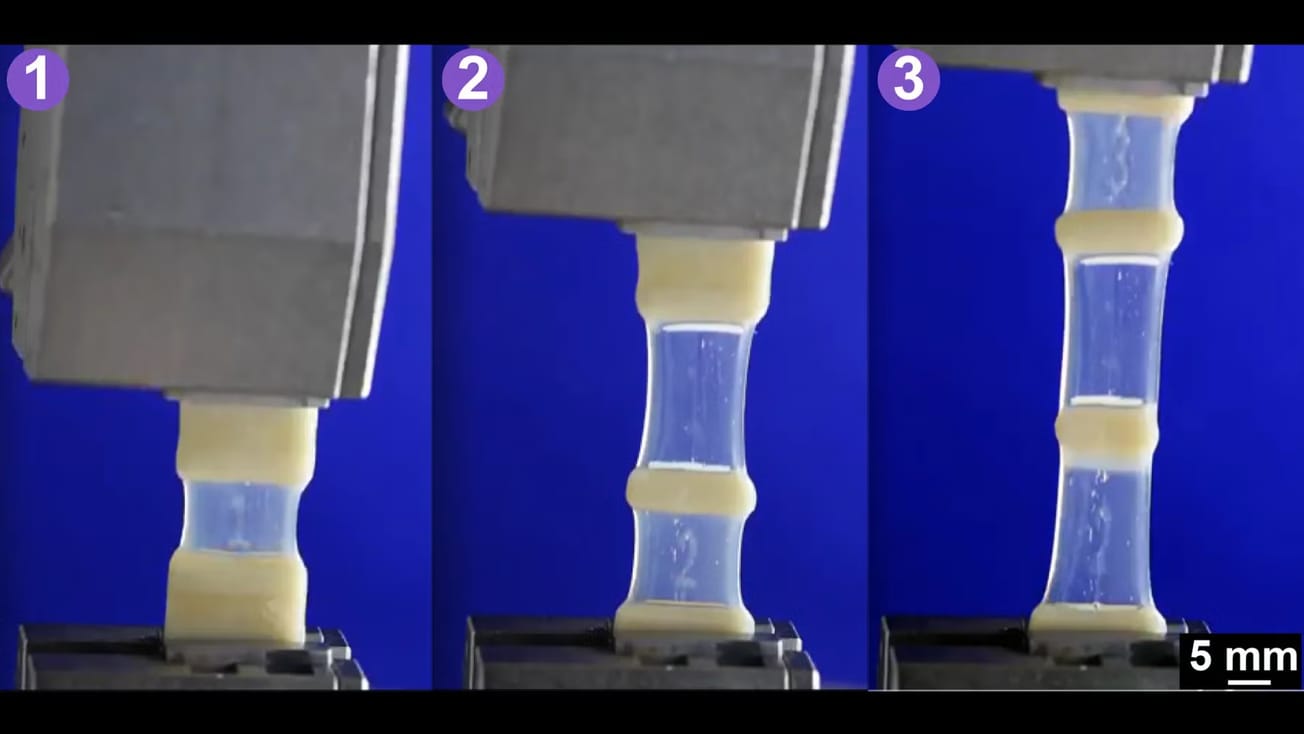

Infra-Architecture Lab frames its approach as pollinator tectonics: embedding cavities, niches, and surfaces into architecture that double as nesting zones, feeding sites, and movement corridors. Instead of treating plants or habitats as decorative add-ons, the project integrates them into the core of the building’s performance.

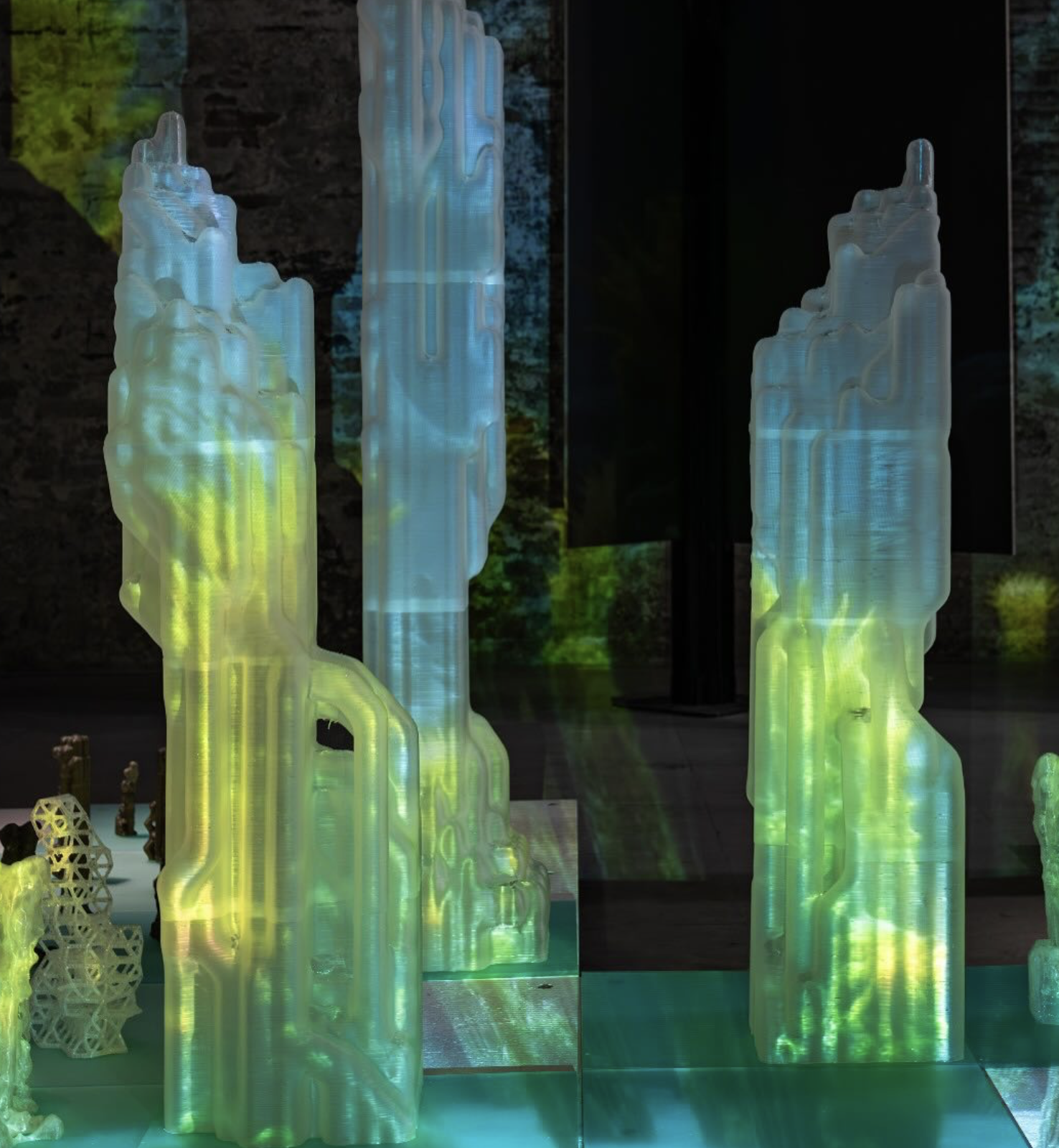

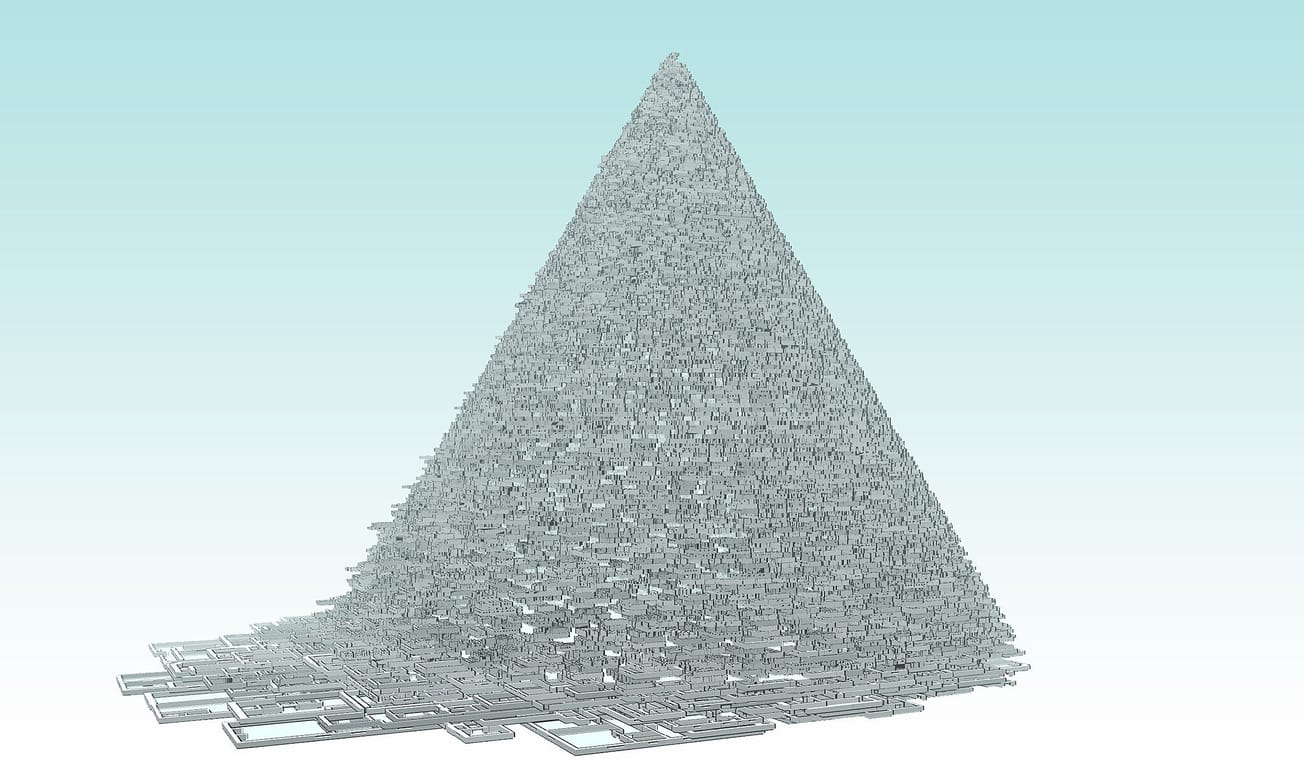

The Sydney prototype illustrates this principle. The structure is porous and layered, with gradients between interior and exterior spaces. Cavities are sized and angled to host native bees, while modular planters provide nectar and pollen sources. By weaving ecological function directly into the building’s skeleton, Wild Futures shifts architecture from sealed mass to living infrastructure.

This approach reinterprets ornament, long debated in architectural history. Rather than aesthetic embellishment, ornament here is treated as productive—serving a role in biodiversity. It positions architecture not as a barrier to ecological systems but as a participant in them.

From Prototype to Urban Strategy

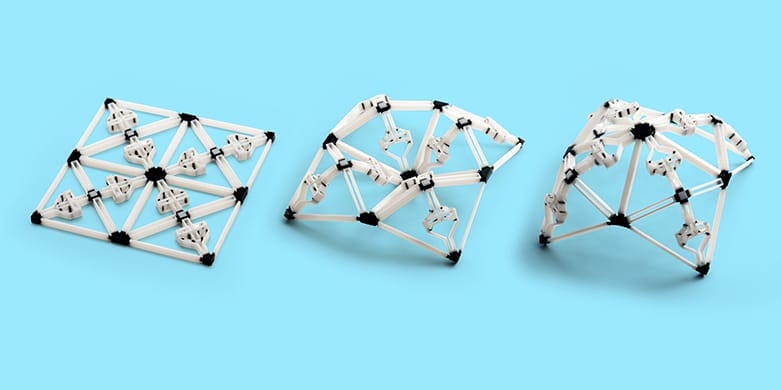

While the Sydney prototype demonstrates feasibility, Wild Futures is conceived as a system that could scale across urban contexts. Widespread adoption could generate pollinator corridors—networks of habitat distributed through dense neighborhoods that reconnect fragmented ecosystems.

Scaling this idea requires more than design innovation; it demands infrastructural change. For pollinator-conscious architecture to become standard, it would need to integrate with biodiversity policies, zoning codes, and building regulations. The shift parallels earlier moments when sanitation, fireproofing, or ventilation became codified as essential to public health. In this frame, habitat provision for nonhuman species could become equally fundamental. The challenges are significant. Different pollinators require different conditions: soil depth, cavity size, plant species, or microclimates. Wild Futures addresses this by emphasizing modularity—adaptable components that can be tailored to different ecological contexts. Yet ecological performance is difficult to standardize, and its effectiveness requires collaboration with ecologists, horticulturalists, and policymakers.

Architecture as Ecological Justice

What sets Wild Futures apart from many green architecture projects is its emphasis on ecological justice. Urban development has historically privileged human needs while displacing other species. By centering pollinators in the design process, Infra-Architecture Lab reframes architecture as a tool for rebalancing those inequities.

This orientation connects the project to a wider movement in design research that expands the definition of infrastructure beyond human use. Cooking Sections’ Climavore rethinks how food and architecture adapt to shifting ecological cycles, while Design Earth has mapped planetary-scale infrastructures as speculative design. Wild Futures shares these ambitions but grounds them in a modular, buildable system with immediate ecological relevance. The project also demonstrates the need for disciplinary hybridity. To design architecture that supports pollinators, architects must engage with biology, horticulture, and climate science. This aligns with the growing discourse on posthuman design, where the value of creative practice is measured not only by cultural impact but also by ecological function.

Toward a Wild Urbanism

The future of Wild Futures depends on factors beyond architecture. Municipal policies, cultural perceptions, and investment in biodiversity infrastructure will determine whether pollinator-conscious design remains experimental or becomes integrated into the urban fabric. Yet the project is valuable precisely because it pushes the boundaries of architectural discourse.

For architects, Wild Futures is a provocation: buildings are not inert shells but active participants in ecological systems. For urban planners, it presents a low-tech, distributed approach to biodiversity infrastructure that could scale incrementally across neighborhoods. For cultural observers, it frames architecture as part of a multispecies commons.

As biodiversity loss accelerates, architecture cannot remain isolated from ecological responsibility. Wild Futures shows how rethinking structure and form around nonhuman needs can generate new directions in design. Its prototypes are modest, but its implications are expansive: cities that serve as habitats not just for humans, but for the species that sustain life itself.