At Tate Britain, Ed Atkins’s retrospective situates itself at the threshold between the algorithmic and the intimate. Spanning moving-image works, embroideries, drawings, and fragments of personal writing, Atkins dismantles the assumption that the digital realm is inherently disembodied. His practice argues otherwise: simulated voices, CGI avatars, and even Post-it notes can transmit something startlingly close to lived sensation. The exhibition makes clear that the dwindling space between technology and human emotion is not abstract speculation but tangible experience.

Avatars With Emotional Weight

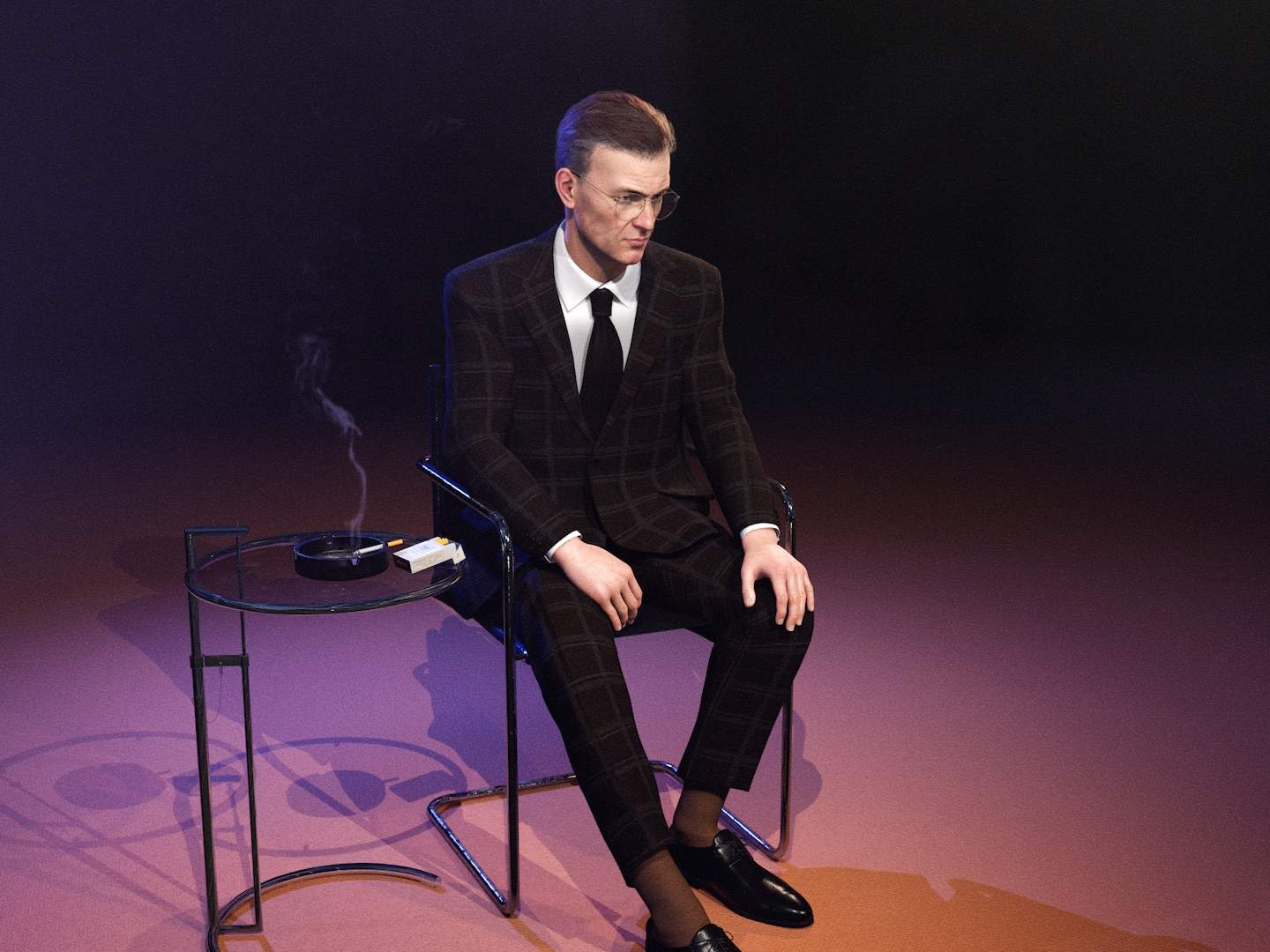

Atkins is best known for his hyper-real CGI avatars—figures that speak in fragmented monologues, sing mournful songs, or glitch into uncanny repetition. Works such as Ribbons (2014) and Hisser (2015) appear in dialogue with more recent pieces, including Pianowork 2 (2023), in which a digitized version of the artist painstakingly performs a minimalist score by Swiss composer Jürg Frey. These avatars are not straightforward characters but emotional proxies. Their digital skin carries the rhythms of exhaustion, grief, and absurd humor.

What becomes striking across the galleries is how weightless projection acquires the force of physical presence. Facial tics, stutters, and breaths—rendered through motion capture and animation—resonate as though they belonged to a body in the room. The effect underscores a cultural shift: when the mechanics of simulation are exposed rather than concealed, digital work can feel less like spectacle and more like an extension of human vulnerability.

Hand-Drawn Notes and Embroidered Grief

Against the scale of CGI projections, the exhibition anchors itself with an array of handmade artifacts. Hundreds of Post-it notes, drawn for Atkins’s young daughter during lockdown, form a grid of simple images and surreal characters. These sketches—some affectionate, others grotesque—sit alongside colored-pencil self-portraits and embroidered works.

Here, the connection between digital work and analog artifact is not presented as a stark contrast but as a continuum. The notes echo the avatars’ monologues: fragments of intimacy, half jokes, half confessions. Both exist in translation between inner experience and mediated surface. Atkins’s embroidery similarly complicates distinctions between screen-based art and tactile making. Stitches trace out states of mind, extending the emotional register of his video works into fabric.

Technology as a Medium for Mourning

The exhibition’s most affecting moment arrives with Nurses Come and Go, But None for Me (2024), a two-hour film in which actors Toby Jones and Saskia Reeves read from the cancer diary of Atkins’s father. The performance transforms personal documentation into public artifact, situating loss within the mechanics of staging, voice, and projection.

What might otherwise appear as private documentation becomes a study in how technology mediates grief. The diary, transposed into spoken performance and cinematic scale, confronts the audience with the paradox of technological intimacy: the more mediated the material, the more vulnerable it becomes.

The Shrinking Divide

Taken together, the works refuse to separate affect from digital form. Atkins suggests that human feeling is not eroded by computational media but reshaped through it. His avatars, notes, and films demonstrate that technology no longer functions as a barrier to empathy but as its conduit.

The show foregrounds an important question: if emotional presence can be transmitted through code, texture, and performance interchangeably, what remains uniquely human? Atkins does not provide an answer, but he reframes the inquiry—away from authenticity versus artifice, and toward the experiential truth of how feelings circulate across mediums.

Digital Tools, Human Residues

Ed Atkins’s retrospective at Tate Britain is less about the novelty of digital tools than about what they carry: the cadences of grief, the awkward humor of self-portraiture, the weight of mortality. In tracing the shrinking divide between digital worlds and human feeling, Atkins demonstrates that the technologies shaping contemporary culture are not detached from emotion but saturated with it. For visitors, the exhibition is less a spectacle of virtual technique than an invitation to confront how technology has already become inseparable from the texture of lived experience.

The exhibition closes at Tate Britain 25 August 2025.