When museums digitize their archives, it’s usually to expand access. UNESCO’s new Virtual Museum of Stolen Cultural Objects does something radically different: it uses technology to make visible what has been taken—and to eventually erase itself. Launched in 2025, the online platform brings together 3D models of stolen, looted, or illicitly trafficked cultural artifacts from across the world. But unlike most museums, it measures success not by how much it collects, but by how much it loses. Each time an object is repatriated to its rightful home, it disappears from the virtual gallery. This inversion of the museum’s traditional logic—accumulation—signals a new phase in the ethics of digital heritage. The project reimagines not only how we exhibit lost culture, but how institutions can use virtual tools to advocate for cultural justice

A Museum Designed to Shrink

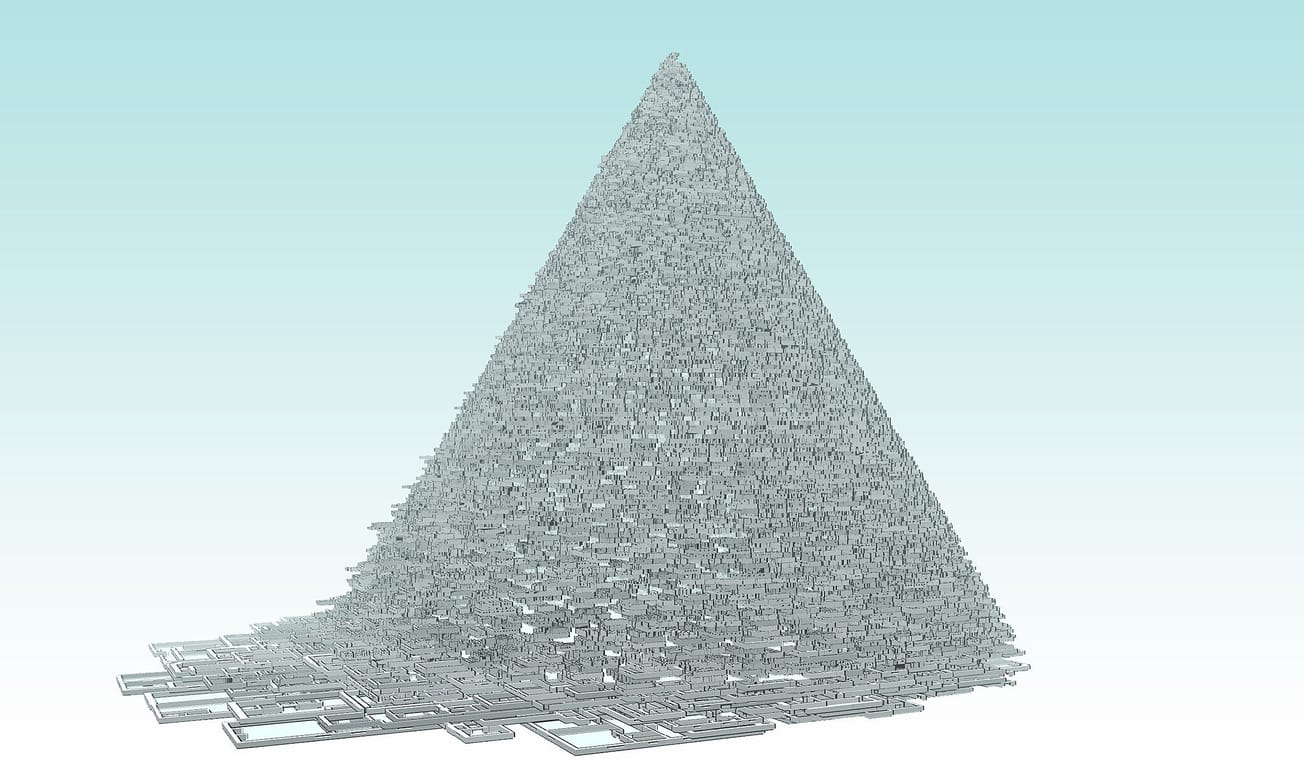

Developed by UNESCO in collaboration with INTERPOL and national heritage authorities, the Virtual Museum of Stolen Cultural Objects currently features around 200 digital artifacts—ranging from bronze sculptures and manuscripts to ceremonial objects and archaeological fragments—each meticulously rendered in high-resolution 3D. Visitors can navigate its immersive galleries as they would a physical museum, exploring the contours and textures of objects that have been missing, in some cases, for decades.

Each entry is accompanied by a layered narrative: where the object originated, how it was stolen, and what efforts are underway to recover it. What initially reads as an impressive digital archive quickly reveals itself as a global index of cultural loss. The curatorial logic is deliberately paradoxical. The museum’s collection is meant to shrink over time, with each disappearance marking a successful restitution. As UNESCO’s Assistant Director-General for Culture, Ernesto Ottone Ramírez, explained at MONDIACULT 2025 in Barcelona, the museum’s goal is for its collection “to shrink, not grow.” Its gradual disappearance would signify a world in which stolen heritage has been returned.

Cultural Memory as Digital Infrastructure

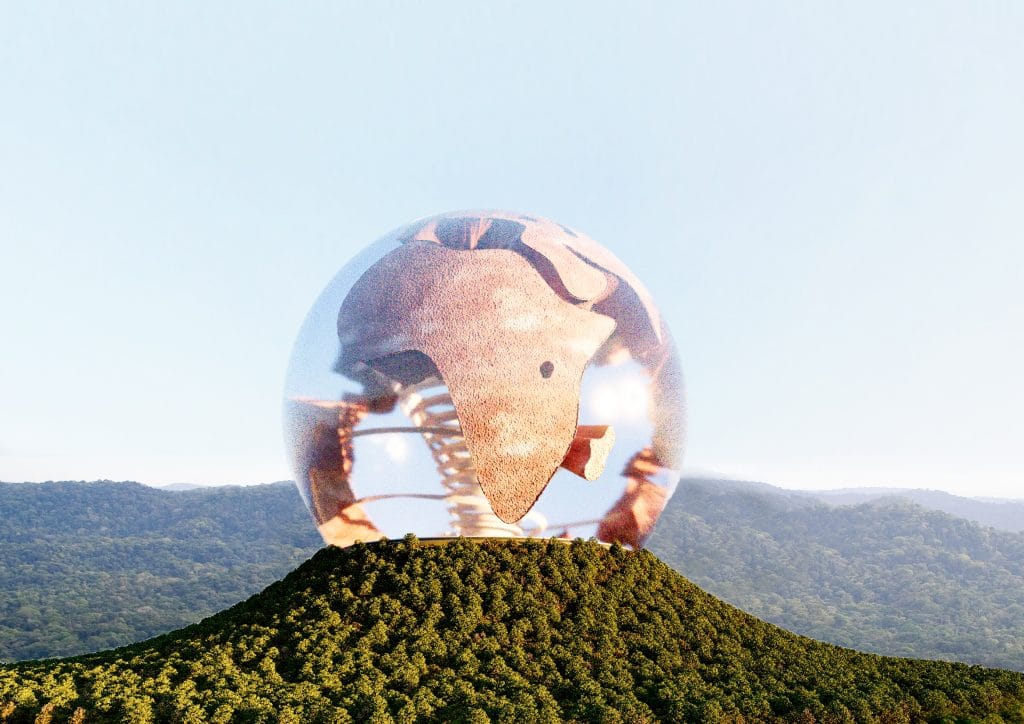

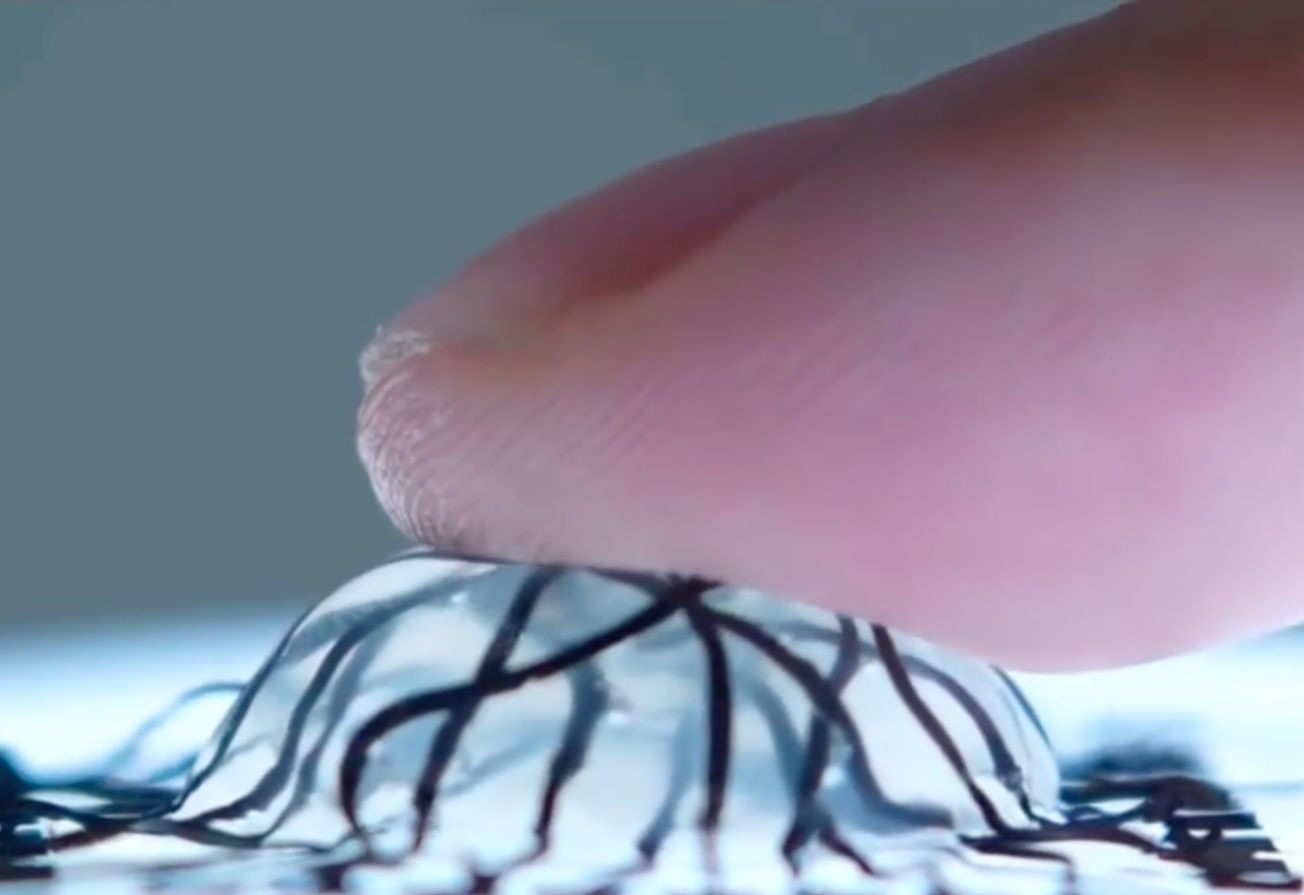

The museum’s design takes inspiration from the symbolic form of the baobab tree—a central metaphor chosen by UNESCO to represent endurance, community, and continuity. Often called the “tree of life” across many African traditions, the baobab embodies resilience and rooted connection. Its branching form becomes a metaphor for the museum’s structure: decentralized, interlinked, and alive.

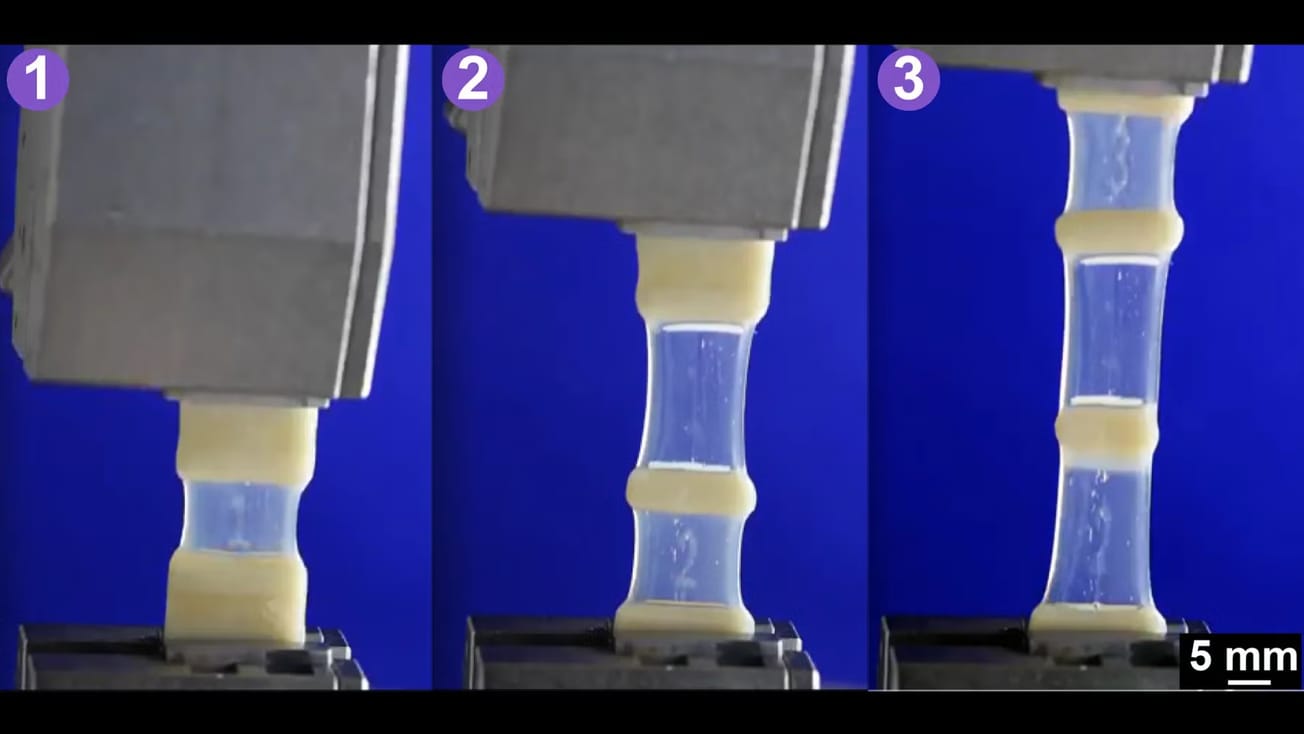

Each digital gallery functions as a node in a wider network of cultural memory. The 3D reconstructions—produced using a combination of photogrammetry and laser scanning—are developed in partnership with museums, universities, and law enforcement agencies. These digital replicas serve multiple purposes: as visual evidence in efforts to track illicit trade, as educational resources for cultural institutions, and as public-facing artifacts that restore a measure of access to displaced heritage.

At its core, the project is also a statement about digital sovereignty. By storing and presenting these objects in a globally accessible virtual space, UNESCO bypasses many of the physical and jurisdictional limits that have long constrained restitution. The museum becomes a shared space for accountability and remembrance, where access—not possession—defines value.

The Politics of Visibility

The virtual museum launches at a time when global debates over restitution are accelerating. European institutions, including the British Museum and the Musée du quai Branly, have faced sustained pressure to return colonial-era artifacts. Yet restitution is rarely straightforward—it involves complex legal frameworks, diplomatic negotiation, and painstaking questions of provenance that can take years to resolve.

The UNESCO platform doesn’t settle these disputes, but it reframes them. By visualizing the scale of cultural theft, it shifts restitution from abstract policy to tangible visibility. Seeing around two hundred stolen artifacts assembled in one digital space makes it difficult to ignore the systemic nature of cultural displacement. At the same time, the museum raises questions of representation and consent. Who determines which objects appear? How are communities of origin involved in shaping their narratives? UNESCO has emphasized that the platform was developed in consultation with national cultural authorities and heritage agencies, though the ongoing challenge remains ensuring that restitution stories are told with, not merely about, the affected communities.

The digital medium adds further complexity. The 3D scans—precise, detailed, and endlessly reproducible—blur the boundary between visibility and replication. When a virtual copy circulates freely, what does that mean for ownership? Can a digital rendering of a looted object ever be neutral, or does it risk becoming another layer of appropriation?

The Museum as Future Prototype

As a prototype for how institutions might use digital media for ethical advocacy, the UNESCO Virtual Museum is conceptually groundbreaking. It transforms the museum from a repository into a temporal mechanism—an evolving ledger of accountability.

The “shrinking museum” model challenges how cultural institutions measure value. Instead of equating prestige with size, the project inverts the hierarchy: absence becomes proof of success. Conceptually, it offers a framework that could influence how virtual archives address other global forms of loss—from climate-displaced architecture to endangered biodiversity—using digital preservation not as a substitute for loss, but as a prompt for repair. Still, the project faces tangible constraints. High-fidelity 3D modeling is costly and technically demanding. Maintaining the infrastructure over decades requires funding, cybersecurity, and long-term stewardship. And technology alone cannot restore trust or undo colonial histories of extraction. The museum’s power lies less in resolution than in visibility—in its capacity to convene attention and sustain accountability.

UNESCO’s Virtual Museum of Stolen Cultural Objects is not a static monument to loss; it is an evolving system for memory, advocacy, and repair. Its paradox is deliberate: a museum that succeeds by disappearing. As it does, it invites cultural institutions everywhere to reconsider what it means to hold, display, and ultimately let go.