For years, computational design has been defined by modeling: parametric scripts generating geometry, simulations optimizing performance, machine learning systems producing form variations. Matter entered at the end of the pipeline—fabricated after computation had already concluded. Physical computation reverses that sequence. When behavior is encoded directly into material structure, topology, and compliance, computation no longer sits exclusively in silicon. It unfolds through deformation, phase change, distributed actuation, and multi-stable geometry. Under these conditions, design practice shifts. If materials compute, designers are no longer producing static forms—they are authoring behavioral systems.

Encoding Behavior in Matter

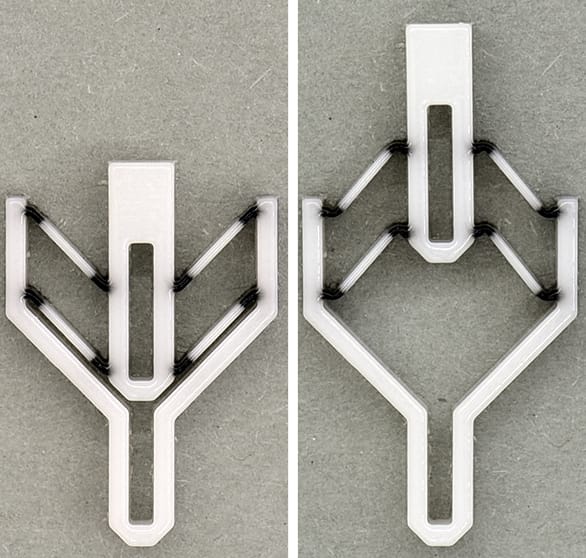

At the forefront of this shift is Lining Yao and her Morphing Matter Lab at Carnegie Mellon University. Yao’s research focuses on materials that change shape in response to environmental stimuli such as water and heat. Her team has developed 3D-printed hydrogels and bio-based composites whose microstructures determine how they swell, curl, or fold when exposed to moisture. In these systems, transformation is not animated externally. It is embedded in composition and geometry. Print patterns, fiber orientation, and material gradients encode how the structure will respond. Once fabricated, the object carries its own conditional logic.

This approach alters the workflow fundamentally. Instead of modeling a final geometry and simulating its performance, the designer defines a transformation rule: how much swelling occurs, along which axis, at what threshold. Form becomes a temporal expression of material instruction. Fabrication is no longer downstream of computation; it is computation. Such systems also operate with minimal external energy. Hygroscopic and hydrogel-based responses rely on environmental input rather than continuous electrical power. The substrate encodes its response behavior in material structure.

Projects such as MorphingSkin extend the lab’s morphing-material research into thin, programmable surface systems, where patterned structures encode how a material curls, folds, or textures in response to environmental input.

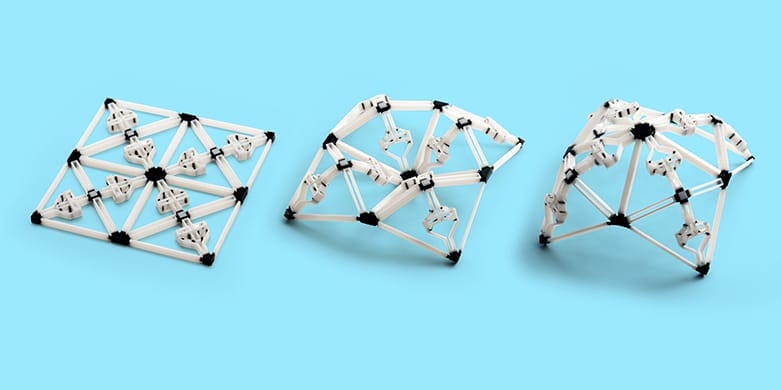

Topology as Instruction Set

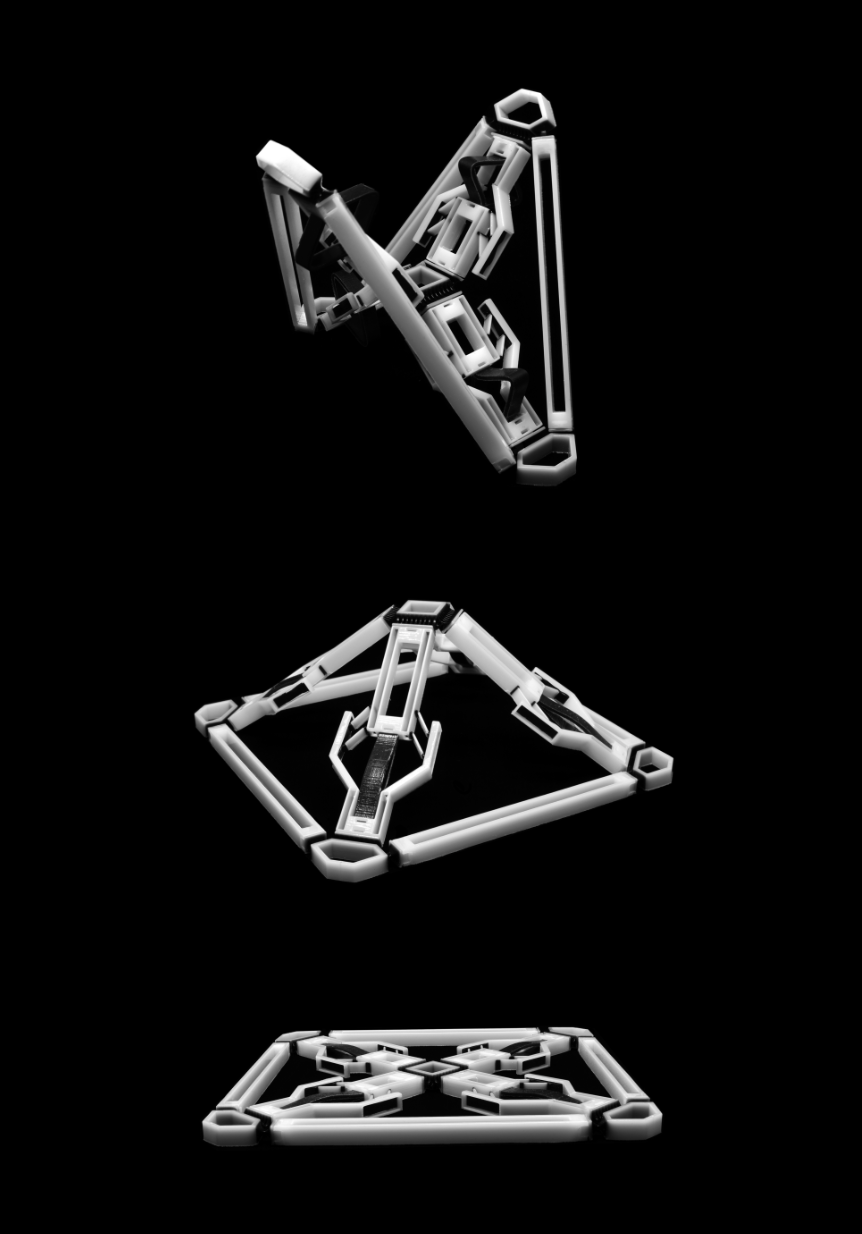

While morphing materials encode behavior through chemistry and microstructure, programmable mechanical metamaterials encode behavior through geometry. At ETH Zurich, Kristina Shea leads research into multi-stable structures whose topology determines how they move and reconfigure under load. These latticed systems can snap between stable states without continuous energy input. In many cases, their behavior is governed by the arrangement of beams, hinges, and cellular patterns rather than continuous motorized control. A shift in topology alters how stress propagates through the structure. Multi-stability is achieved through structural design rather than embedded electronics.

In this model, geometry determines the system’s possible state transitions. The designer specifies relationships—angles, thicknesses, and connection points—that define how the structure responds to applied force. Once fabricated, the system behaves according to its geometry and material properties; its response is inseparable from its structural logic. For practice, this demands a shift from composing surfaces to engineering possibility space. The designer is not asking what shape to produce, but what behaviors to enable. In multi-stable metamaterials, analysis and fabrication converge: topology carries the behavioral rule.

The implications extend beyond laboratory prototypes. Such structures suggest architectural components, deployable systems, and adaptive assemblies that respond passively to load and environment. Maintenance, durability, and tolerance stacking become central design concerns. Wear and fatigue are operational variables embedded within the system’s long-term behavior.

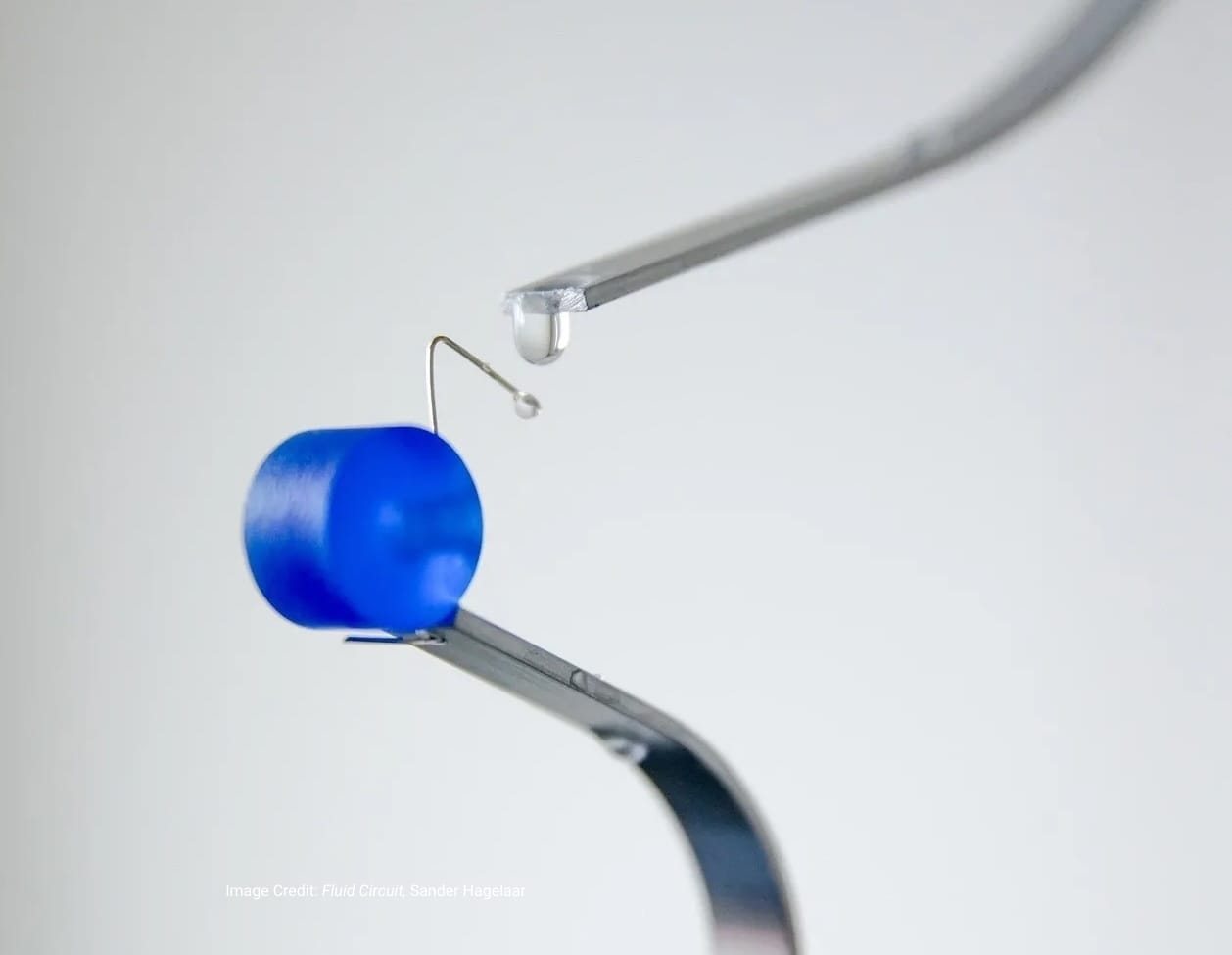

Distributed Intelligence in Soft Robotics

If Yao’s work embeds behavioral response in material microstructure and Shea’s encodes it in topology, the soft robotics research of Daniela Rus shows how embodied mechanics scale into autonomous systems. At MIT’s Computer Science and Artificial Intelligence Laboratory (CSAIL), Rus and collaborators have developed both soft robotic systems—such as pneumatically actuated grippers—and self-reconfigurable modular robots like the M-Blocks platform. These projects explore how structure, material compliance, and distributed interaction contribute to adaptive behavior.

In soft robotics, body and control are tightly coupled: morphology and material dynamics can simplify control requirements by shaping how forces propagate and how the system responds to contact. Feedback emerges from interaction between material and environment, enabling behaviors that are difficult to achieve with rigid mechanisms alone. Designing these systems means configuring how sensing, actuation, and structure interrelate. Creative control shifts from sculpting a static object to specifying behavioral coupling—compliance gradients, actuator placement, and modular connectivity—then iterating through physical calibration as the robot’s behavior is validated in real operating conditions.

From Artifact to System

Across these examples, a consistent pattern emerges. The designer’s task is no longer limited to producing a finished artifact. Instead, it involves defining a rule-bound system that continues to operate after fabrication. This transformation has practical consequences. Iteration cycles expand beyond digital simulation into material calibration. Environmental variability—humidity, load, temperature—affects output. Tolerances, fatigue, and degradation become computational parameters. The system’s lifespan is part of its logic.

Physical computation also complicates narratives of decentralization. Many responsive systems still rely on embedded electronics and complex supply chains. Multi-stable structures may eliminate continuous energy input but require precision manufacturing. Soft robots reduce control overhead yet depend on sophisticated materials research. The shift from form-making to rule-making does not remove control; it redistributes it across structure, material, and feedback loops.

At the same time, as artificial intelligence increasingly automates symbolic production—generating images, text, and parametric scripts—physical computation anchors intelligence in tangible substrates. It positions material systems as active participants in sensing and response. In this framework, the designer becomes less a stylist of surfaces and more an author of conditions. Material choice is a computational decision. Topology is a behavioral script. Fabrication is an encoding process. When matter computes, design becomes the practice of shaping how systems act—not just how they look.