Generative AI is now embedded across creative workflows, yet the systems that enable it—cloud platforms, data pipelines, and large-scale training cycles—carry environmental and political costs that remain largely out of view. As models expand and inference becomes ubiquitous, the material footprint of computation is becoming a critical design concern. Circular data, a framework centered on minimizing, reusing, or localizing datasets and compute cycles, offers a way to rethink how creative AI systems are built and sustained. Across the field, practitioners are exposing the hidden resource flows behind digital systems and proposing alternative infrastructures that prioritize ecological and ethical responsibility.

Making AI’s Materiality Visible

Joana Moll has long challenged the assumption that digital interactions are immaterial. Her investigations into the operational complexity and energy implications of online services—such as The Hidden Life of an Amazon User, which exposes the dozens of scripts and tracking processes triggered by a simple purchase—reveal how digital activity depends on continuous resource consumption. Her broader work examines the carbon footprint of tracking and advertising infrastructures, making visible the environmental impact of data-intensive services that typically operate out of sight.

While Moll does not focus specifically on generative AI, her research on the material costs of digital systems provides a critical foundation for understanding the environmental pressures that AI development amplifies. Large-scale models rely on electricity, specialized hardware, and distributed cloud infrastructure at every phase of their lifecycle, from dataset preparation to training and inference. Recognizing these resource flows is essential for any effort to build AI systems with a reduced ecological footprint. A circular data approach builds on this awareness by shifting attention from unbounded dataset growth toward more intentional, efficient, and context-driven data practices.

Mapping the Politics of Infrastructure

If Moll foregrounds the material costs of computation, Ingrid Burrington reveals the infrastructures that make those costs possible. Her documentation of fiber-optic cables, data centers, and the territorial footprints of networked systems offers a lens through which to understand the physical architecture that AI now depends on. Burrington’s research surfaces the civic and geopolitical dimensions of the cloud: the energy grids that power data centers, the land they occupy, and the regulatory structures that govern them.

Working with generative models, this perspective reframes cloud usage as an infrastructural choice rather than a neutral technical detail. Decisions about where data is stored, which providers host training runs, and how models interface with networks all have environmental and political consequences. Circular data extends naturally from this view, emphasizing locality, transparency, and an awareness of how computational workloads circulate across global infrastructures.

Designing Alternative Pipelines

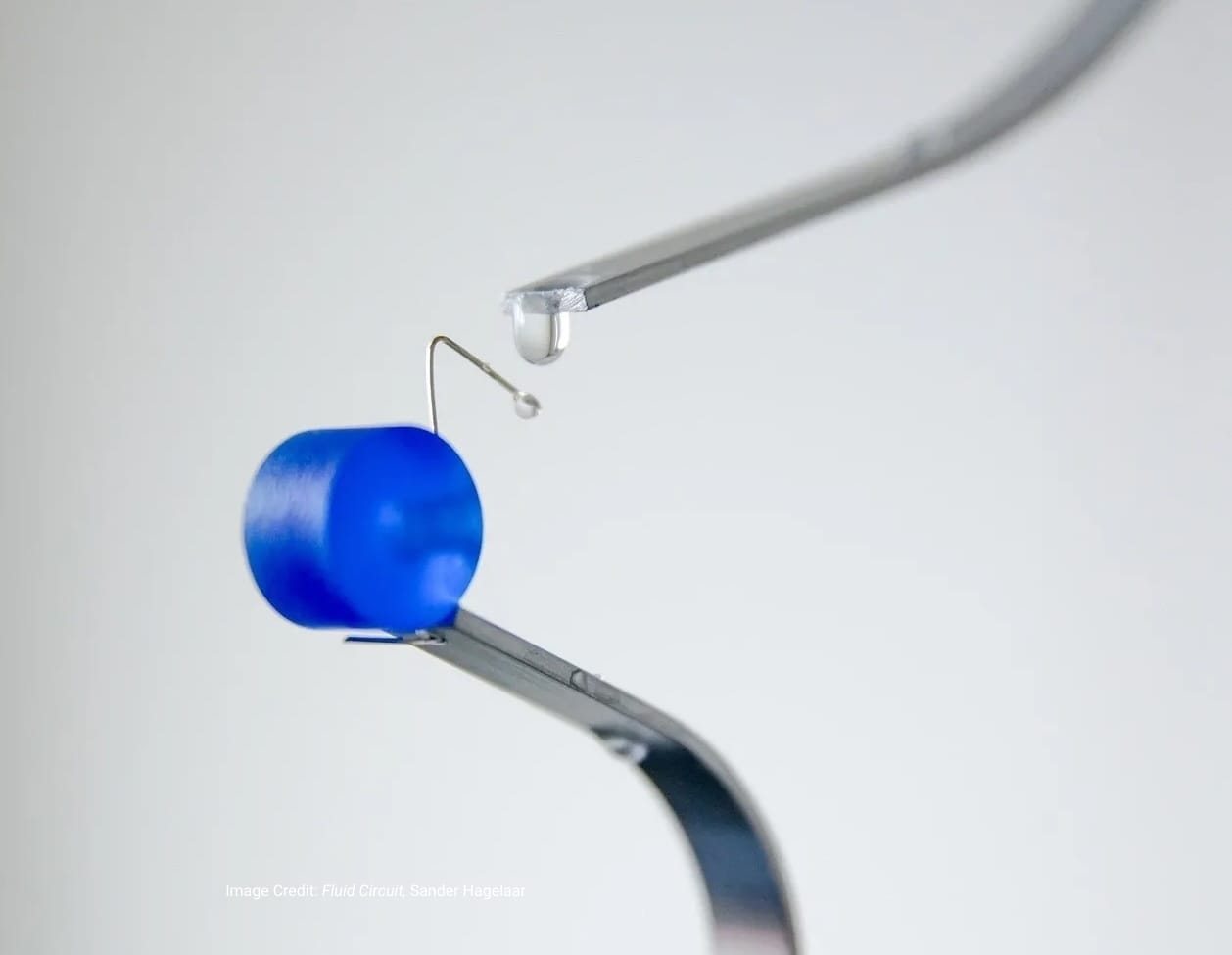

Creative technologists are also demonstrating how pipeline design itself can counter the default logic of large-scale, cloud-dependent AI. Björn Karmann’s work offers concrete examples of this shift. Project Alias places a programmable, user-controlled device over the microphones of commercial smart speakers. It continuously emits noise to block passive listening and, when activated, plays a custom wake word that allows the speaker to receive commands. The device inserts a local layer of control between users and cloud-based assistants, reducing unnecessary data transmission and challenging the assumption that continuous upstream audio is required for usability.

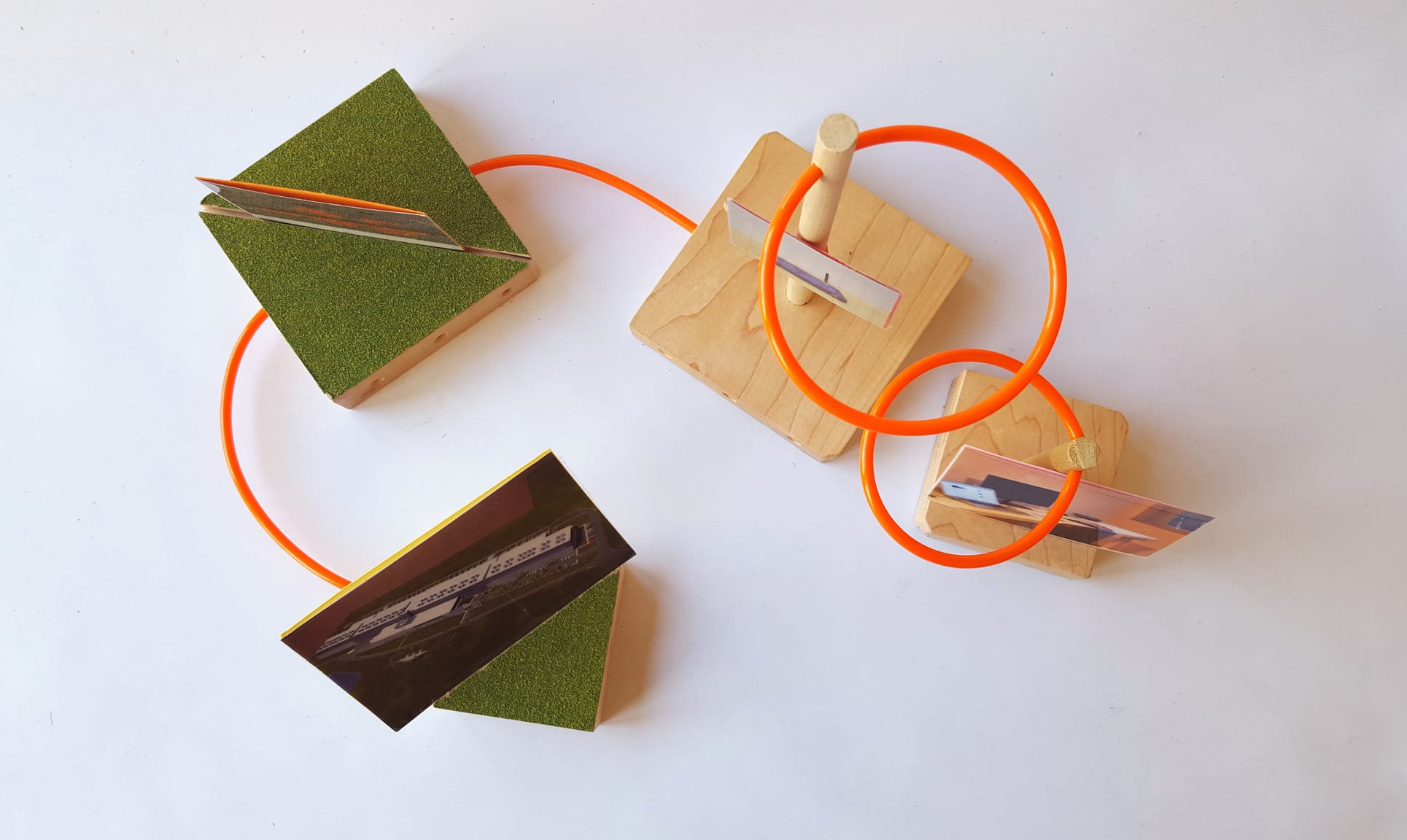

Karmann’s Paragraphica likewise explores alternative relationships between data and output. Instead of using photographic light capture, the system gathers geolocation and environmental data—such as place, time, or nearby points of interest—and uses those inputs to generate an image via existing pre-trained models. While these models are still built on large-scale training, the project shifts emphasis away from dataset accumulation toward contextual sensing and recombination. For creative technologists, this approach demonstrates how constrained, situational data can open new modes of experimentation without defaulting to building or retraining large models.

These practices reflect the core principles of circular data: reduce transmission, use what is already available, localize where possible, and design workflows that avoid unnecessary compute cycles.

Data Circularity as an Ethical and Political Framework

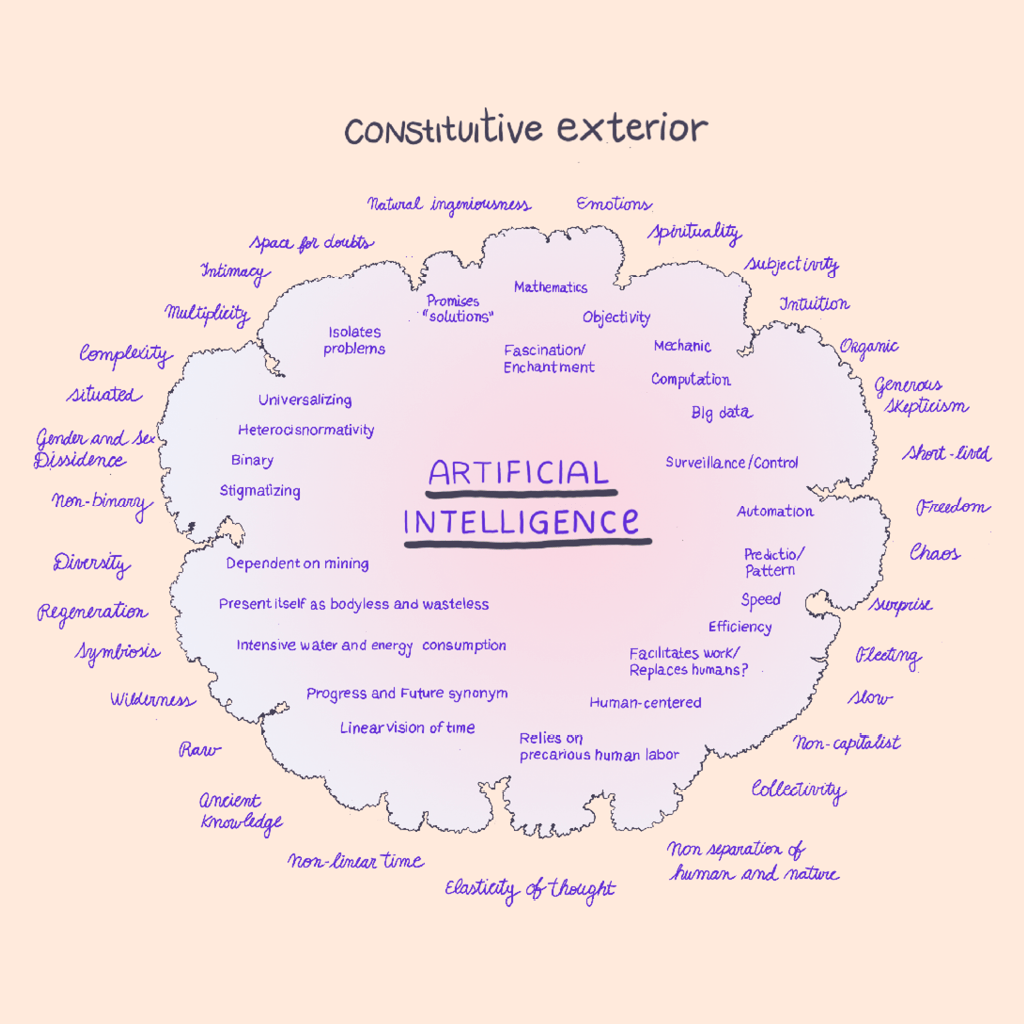

Circular data is not only a technical proposition. Joana Varon and the Brazilian organization Coding Rights expand the conversation to include the rights-based and geopolitical implications of data practices. Their work examines how data collection and AI development reflect broader patterns of extraction, often disproportionately affecting marginalized communities in the Global South. Coding Rights’ analyses of data colonialism, governance, and AI accountability highlight how training datasets—whether newly created or repeatedly reused—shape the power dynamics embedded in computational systems.

Adopting circular approaches, this raises critical questions: What forms of reuse respect community consent? How can localized datasets support autonomy rather than reinforce inequities? As models become more powerful and accessible, sustainable AI must also engage with social and cultural dimensions of data stewardship. Circular data, approached through this lens, integrates ecological responsibility with ethical governance.

Building Toward Sustainable AI Systems

As AI becomes a routine part of creative production, the environmental and infrastructural realities of computation need to become part of the design vocabulary. Circular data offers a way to reframe the lifecycle of training and inference—reducing redundancy, rethinking storage and transfer, and encouraging the use of contextual or localized data. It signals a shift from scale-driven development toward sufficiency, adaptability, and transparency.

Moll’s environmental investigations, Burrington’s infrastructural mapping, Karmann’s speculative pipeline design, and Varon’s rights-based critique together illustrate how a more sustainable AI ecosystem might emerge. Each contributes a different but complementary insight: computation has material limits, infrastructure is political, pipelines can be reimagined, and data governance matters.

The challenge, of course, is to integrate these insights into practice—designing systems that acknowledge their dependencies, minimize their footprint, and align with broader commitments to ecological and social responsibility. Circular data does not solve the environmental pressures of AI outright, but it provides a framework for building systems that consume less, reveal more, and operate with greater accountability as generative computation continues to evolve.