At MIT, researcher and designer Cyrus Clarke has developed Anemoia, an experimental device that explores whether visual images can be translated into olfactory outputs through computationally mediated systems. Situated at the intersection of design research, sensory interfaces, and machine learning, Anemoia is not a commercial product or a claim about automating fragrance creation. It functions as a research prototype that examines how smell—one of the least standardized human senses—might be structured and mediated through technical systems.

Anemoia takes photographs as input and produces corresponding scent outputs via a controlled emission mechanism. Visual features are computationally mapped to olfactory representations informed by learned associations between images, descriptive language, and scent references. Rather than generating a single definitive smell, the system produces an approximation shaped by probabilistic translation rather than direct sensory measurement.

Smell as a Computational Problem

Olfaction has historically resisted digitization. Unlike vision or sound, it lacks a shared representational framework. There is no universal scale for smell, and language used to describe it varies widely across cultures and individuals. These inconsistencies make smell difficult to encode, compare, or reproduce computationally.

Anemoia does not attempt to resolve these ambiguities. Instead, Clarke’s work treats them as constraints. The system operates on the premise that smell can be approximated indirectly, through correlations rather than direct measurement. Visual cues—such as color, texture, and object category—are computationally associated with olfactory descriptors drawn from human-labeled references, which inform the system’s scent outputs. In this structure, smell is treated as probabilistic rather than absolute. A photograph of a forest path may align with descriptors such as woody or earthy, which map to certain aroma molecules. The system does not claim that this is how the scene “actually” smells. It reflects how such scenes are commonly described within the data it draws from.

How Anemoia Works

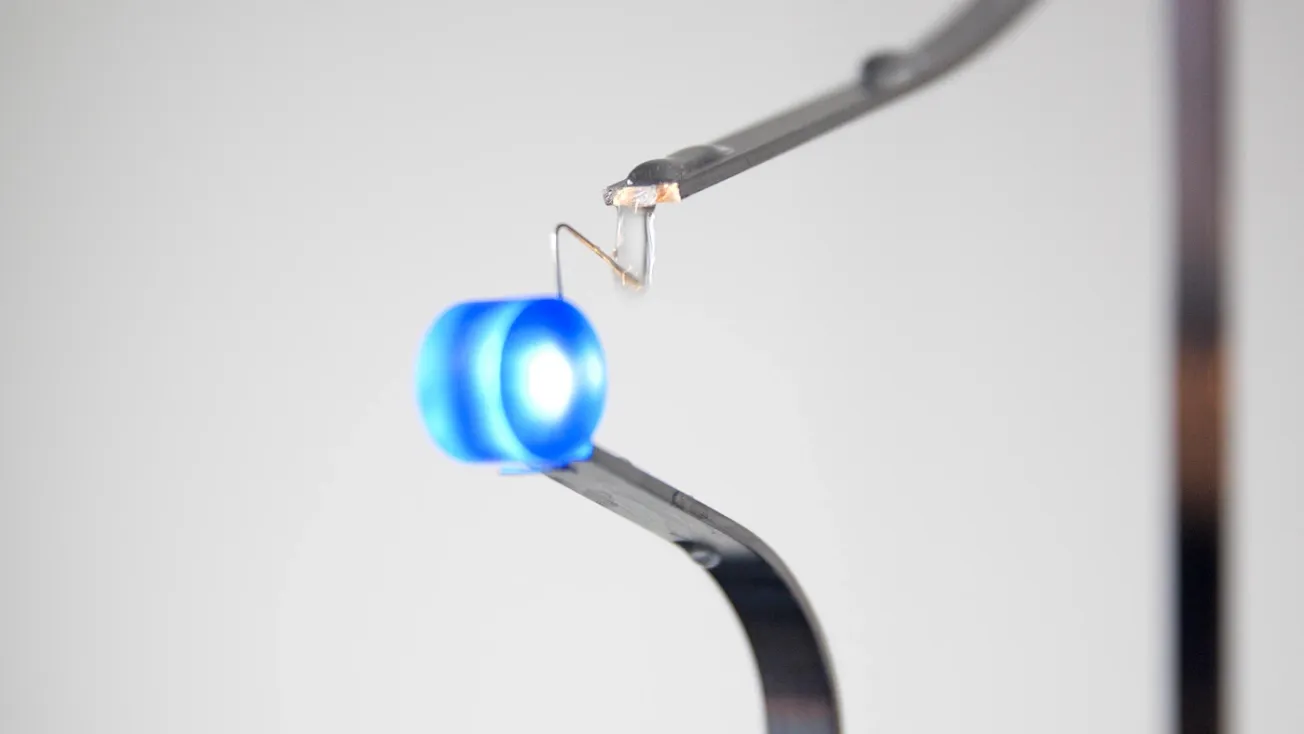

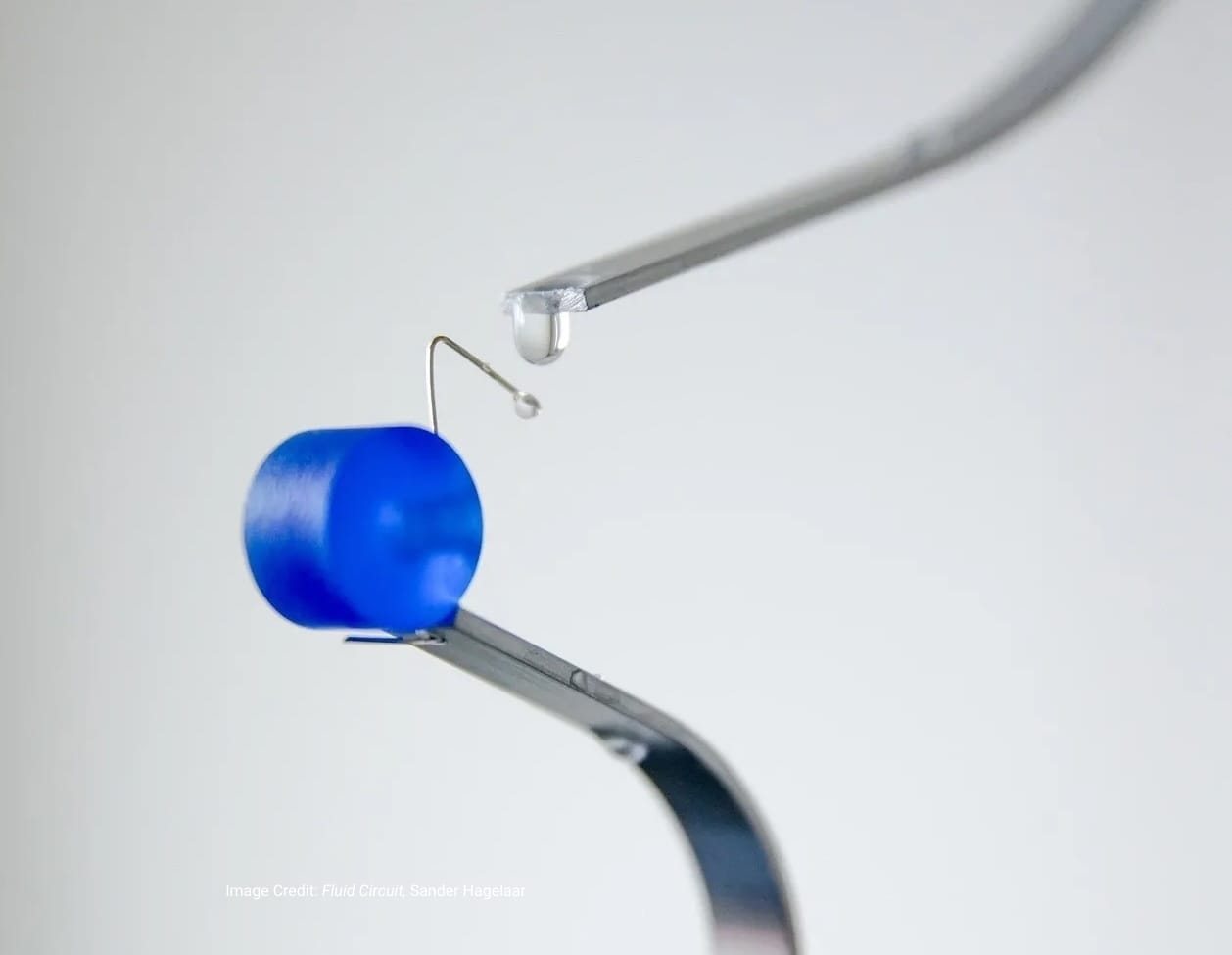

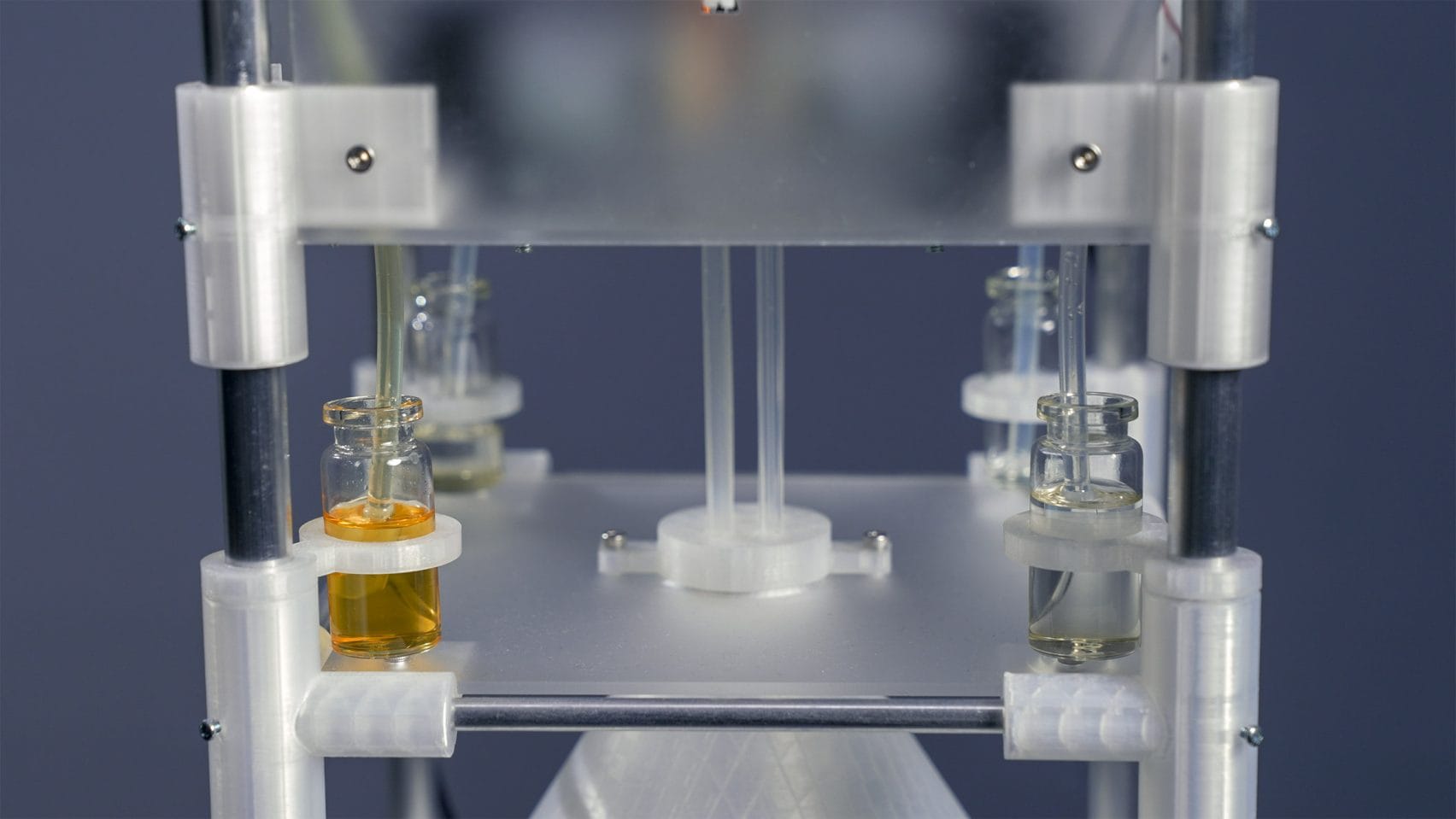

Technically, Anemoia combines image analysis with computational mapping to olfactory components. Images are processed to extract visual features, which are then associated with scent descriptors through trained models. These descriptors inform the system’s scent outputs, which are rendered through a physical emission mechanism. The scent output is delivered via a custom-built hardware interface designed to release controlled quantities of fragrance materials. This physical component is essential to the project. Anemoia is not purely a software model; it is a device that closes the loop between computation and embodied experience. The emitted scents allow users to encounter the system’s translations directly, rather than as abstract data.

Clarke has framed Anemoia as a design probe rather than a finished system. The device exposes the assumptions embedded in its mappings: which visual cues are prioritized, which scent descriptors are available, and how cultural conventions shape the dataset. These choices influence the resulting smells, making the system’s biases perceptible rather than hidden.

Designing Smell as an Interface

By translating images into olfactory outputs, Anemoia reframes smell as an interface layer. Scent becomes something that can be triggered, modulated, and synchronized with other media, rather than remaining ambient or incidental. This framing aligns olfaction with interaction design, where sensory outputs are treated as part of a broader system rather than isolated effects.

The project also foregrounds authorship at an infrastructural level. Decisions about datasets, descriptors, and mappings shape how the device interprets images and what it produces in response. These decisions are not neutral. They embed particular cultural and sensory norms into the system, determining which smells are legible and which are excluded. Anemoia does not suggest that machines can capture the fullness of human smell perception. Instead, it makes visible the gap between lived experience and computational representation. By doing so, it offers a way to examine how emerging technologies may increasingly mediate sensory experience—not by replicating it, but by approximating it through systems of translation.

As design and technology move further into multisensory territory, projects like Anemoia highlight the importance of treating perception itself as a designed system. Smell, once considered too subjective to model, becomes a site where technical, cultural, and aesthetic decisions converge.