Cinema has always been shaped by the tools of its time. From the invention of montage to the rise of digital editing, each technical shift has altered how stories are told and experienced. The latest frontier—algorithmic cinema—pushes this evolution further, transforming narrative into something fluid, generative, and adaptive. Rather than fixed storylines, algorithmic cinema opens the possibility of films that respond to data, viewers, and environments in real time. Will this mark a rethinking of authorship, control, and meaning?

Defining Algorithmic Cinema

Algorithmic cinema refers to the use of computational processes—ranging from machine learning models to procedural systems—to structure, generate, or adapt moving image narratives. It is not simply about digital special effects or editing software; instead, the algorithm itself becomes a narrative engine. In practice, this could mean a film that reorders its scenes based on audience input, a generative system that creates endless variations of a story, or an AI-driven director that assembles footage dynamically.

While interactive cinema experiments date back to the 1960s, what distinguishes algorithmic cinema today is its reliance on data-driven and generative methods. With advances in artificial intelligence, computational creativity, and real-time rendering, filmmakers can design systems that produce outputs that were neither scripted nor entirely predictable.

Beyond Linear Storytelling

Traditional cinema has relied on linear progression: beginning, middle, and end. Even non-linear films, from Pulp Fiction to Memento, are ultimately fixed edits, replayed identically with each screening. Algorithmic cinema disrupts this model. By embedding rules, probabilities, or adaptive logic, a single film may unfold differently every time it is viewed. One audience might experience a tightly wound thriller, while another encounters a slower, more meditative variation of the same material.

This idea has deep roots in media art. Jeffrey Shaw’s The Legible City (1989) transformed narrative into a navigable space of text-based architecture, where viewers determined the sequence of story by moving through a virtual environment.

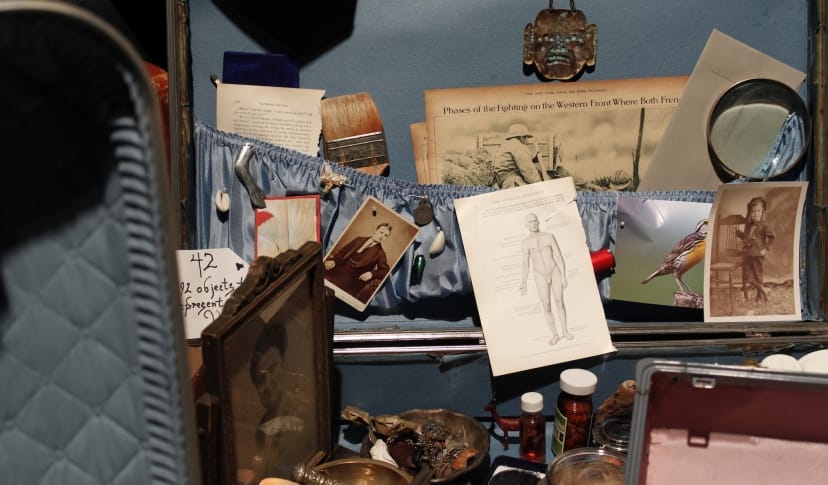

Peter Greenaway’s The Tulse Luper Suitcases (2003–2005) experimented with modular storytelling across films, installations, and online platforms, showing how cinema could be treated as a database rather than a single script. Algorithmic cinema extends these approaches by making variability central to narrative design. In this context, endings are not definitive but contingent, and films become systems of potentialities rather than closed artifacts.

The Role of Data

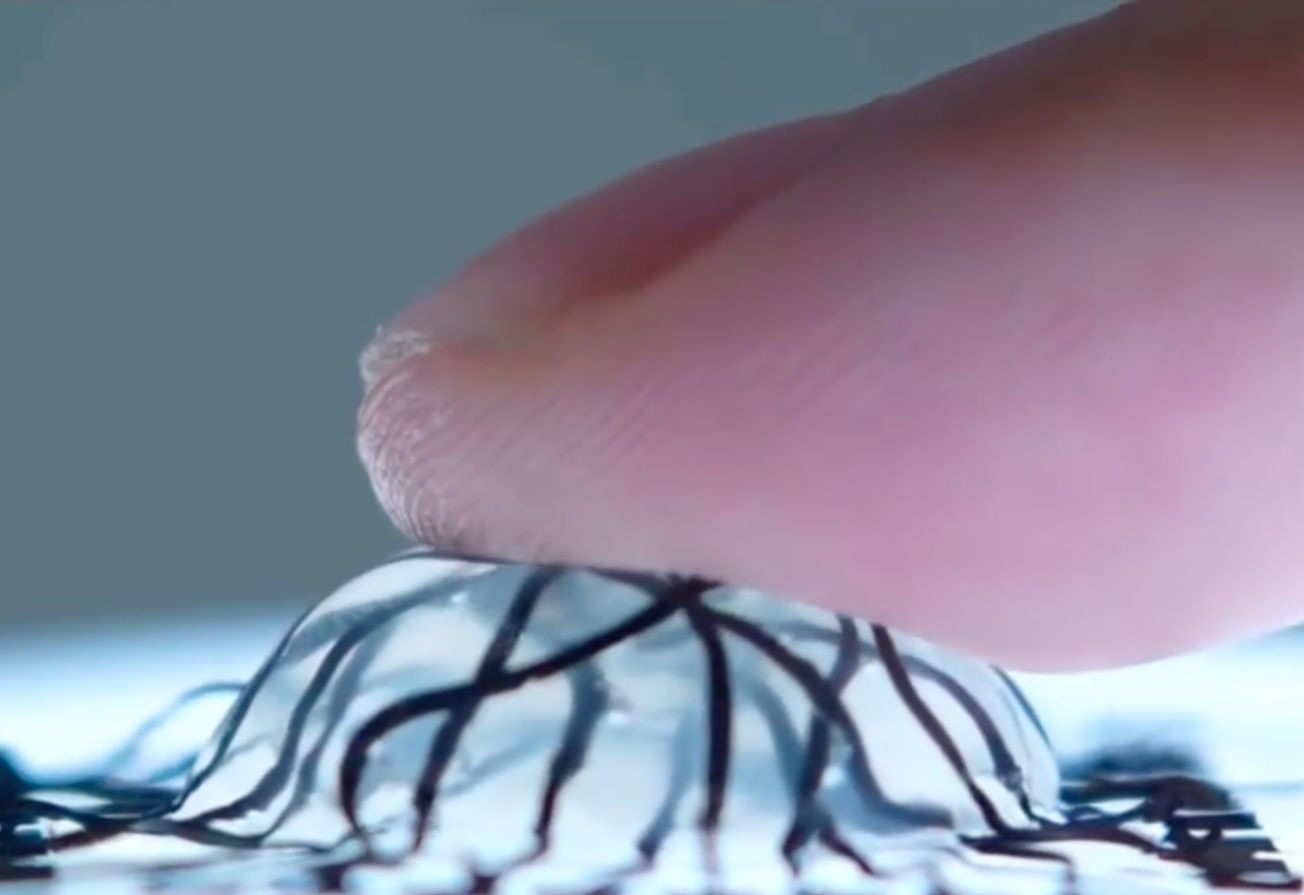

One of the most compelling aspects of algorithmic cinema is its integration with data streams. A generative film might pull from live social media feeds, weather patterns, or biometric sensors, weaving external conditions into its unfolding narrative. Imagine a film whose color grading shifts based on local air quality, or a suspense sequence that intensifies when a viewer’s heart rate spikes. Lev Manovich and Andreas Kratky’s Soft Cinema (2005) offered an early glimpse of this logic. By using software to assemble clips from a database based on metadata, the system generated unique variations of the film in each screening. Similarly, David Rokeby’s interactive video works connected narrative output to human gestures, creating audiovisual responses that changed with each participant.

Such projects raise questions about authorship. If a story is partly shaped by external data, where does creative intent reside? Is the filmmaker an author, a system designer, or a collaborator with algorithms and audiences? These issues are not merely theoretical; they directly influence how stories are produced, experienced, and critiqued.

Case Studies and Experiments

Several contemporary works illustrate the range of algorithmic cinema. The MIT Open Documentary Lab has tracked projects that merge generative algorithms with interactive documentary practice, such as Elaine McMillion Sheldon’s Hollow (2013), where audience choices determine thematic emphasis.

Netflix’s Bandersnatch (2018) brought branching narrative to a mainstream audience. While its decision tree was predefined rather than fully generative, it sparked widespread debate about agency in storytelling and introduced millions to algorithmic structures in film.

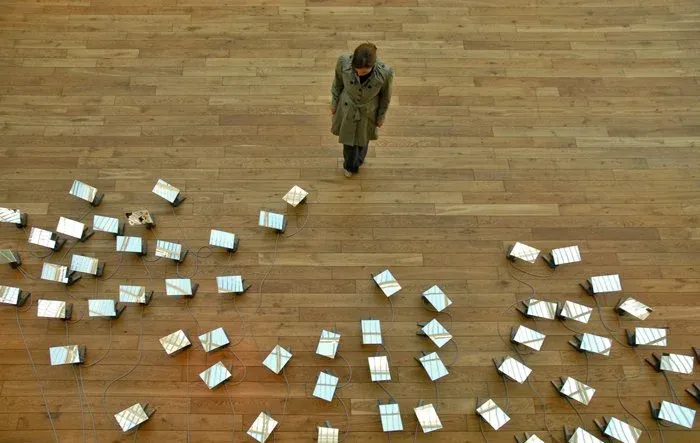

Outside of film, installation-based works also point to the possibilities of algorithmic dramaturgy. Random International’s Audience (2008) consists of robotic mirrors that follow and respond to viewers’ movements, producing an emergent narrative of attention and interaction. While not cinematic in a traditional sense, the piece demonstrates how algorithmic responsiveness can generate story-like experiences in real time.

Implications for Filmmakers

For directors and screenwriters, algorithmic cinema requires a shift in mindset. Instead of authoring a single sequence of events, creators design parameters, rules, and datasets from which narratives emerge. The craft becomes closer to systems design than traditional storytelling. This demands new skills: fluency in coding, understanding of probability, and comfort with indeterminacy.

Yet it also opens creative freedom. Filmmakers can build storyworlds that sustain multiple perspectives and variations, resisting the reductive finality of a single cut. They can also engage with audiences in more participatory ways, designing films that reflect collective input rather than a singular vision. For independent creators, algorithmic cinema offers formats that challenge the dominance of conventional studio filmmaking.

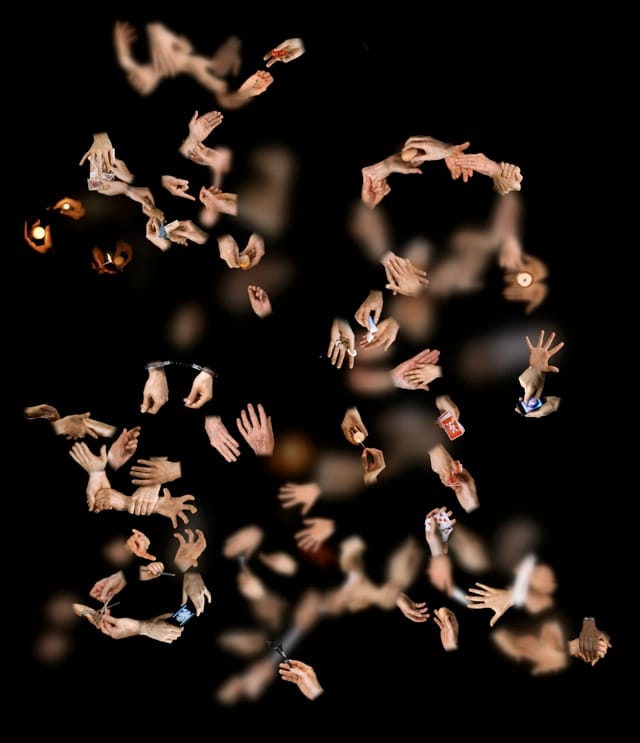

Audiences as Participants

Audience expectations will also shift. Viewers accustomed to fixed, repeatable experiences may need to recalibrate when each screening is unique. This could reintroduce a sense of liveness to cinema, similar to theater or performance art. No two viewings would be identical; instead, films become events that must be experienced rather than endlessly replayed. However, algorithmic variation introduces issues of accessibility and critique. How does one review a film that is never the same twice? How do archives preserve algorithmic works? These challenges will shape the critical and institutional frameworks that surround cinema in the coming decades.

Risks and Challenges

As with all algorithmic systems, the risks of bias, opacity, and commercialization are significant. If a generative film pulls from user data, who controls that data? If algorithms shape plotlines, are they reinforcing existing stereotypes or expanding narrative possibilities? The entertainment industry already uses recommendation algorithms to shape what audiences watch; algorithmic cinema extends that logic into the content itself. Without careful oversight, it risks narrowing rather than diversifying cultural expression.

There are also economic considerations. Dynamic, data-driven storytelling requires computational infrastructure that may be inaccessible to smaller creators. This could widen the gap between resource-rich studios and independent artists unless open-source tools and collaborative platforms emerge.

The Future of Narrative

Algorithmic cinema does not signal the end of traditional filmmaking. Linear storytelling will remain powerful and resonant. But it does introduce a new layer of possibility: stories as systems, films as living organisms, cinema as an adaptive interface. For a generation accustomed to interactive media, personalized feeds, and procedural worlds in gaming, algorithmic cinema may feel less like a radical break and more like a natural extension.

The future of narrative will likely be plural. Fixed, authored films will coexist with generative works, each offering distinct experiences. The value of algorithmic cinema lies not in replacing traditional forms but in expanding the vocabulary of storytelling. By foregrounding variability, responsiveness, and interactivity, it invites filmmakers and audiences to rethink what a story can be—and who gets to shape it.