Search is no longer neutral. Recommendation is no longer benign. The algorithm—once a backend curiosity—has become a political and aesthetic force, mediating everything from visibility to value, creativity to control. As AI systems increasingly shape how we see, think, and create, a growing number of artists and designers are interrogating the fundamental question: Who owns the algorithm?

Digital sovereignty—the right of individuals and communities to control their data, digital infrastructure, and algorithmic environments—has become the frontline of this confrontation. It’s a battleground over authorship, access, and autonomy. And at its core lies a new aesthetic, forged not just from machine learning models but from critical refusals, creative interventions, and postcolonial provocations.

The Politics of Algorithmic Authorship

Algorithms today do more than execute; they author. Large language models like GPT-4 and image generators like Midjourney are routinely celebrated as co-creators, or even stand-ins, for human ingenuity. Yet behind their smooth interfaces lie massive datasets scraped with little regard for consent or context. Authorship, once anchored in identifiable labor and intent, is now entangled with unknowable inputs and automated pattern recognition.

This raises fundamental questions about attribution, compensation, and legitimacy. When AI outputs borrow from centuries of artistic labor, where does originality lie? And who gets to claim ownership when the system itself is trained on the debris of digital culture?

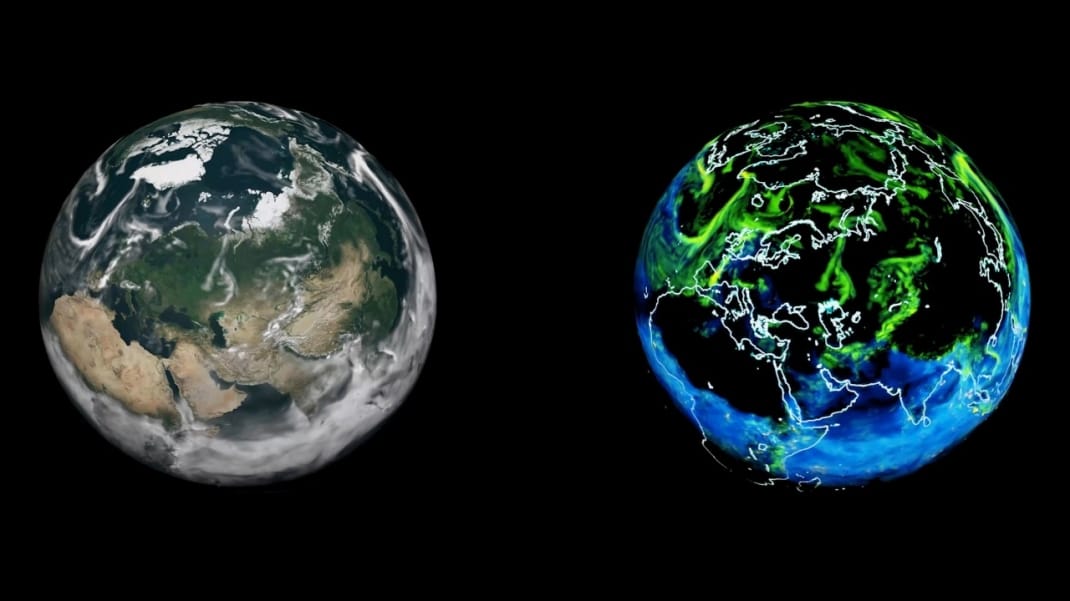

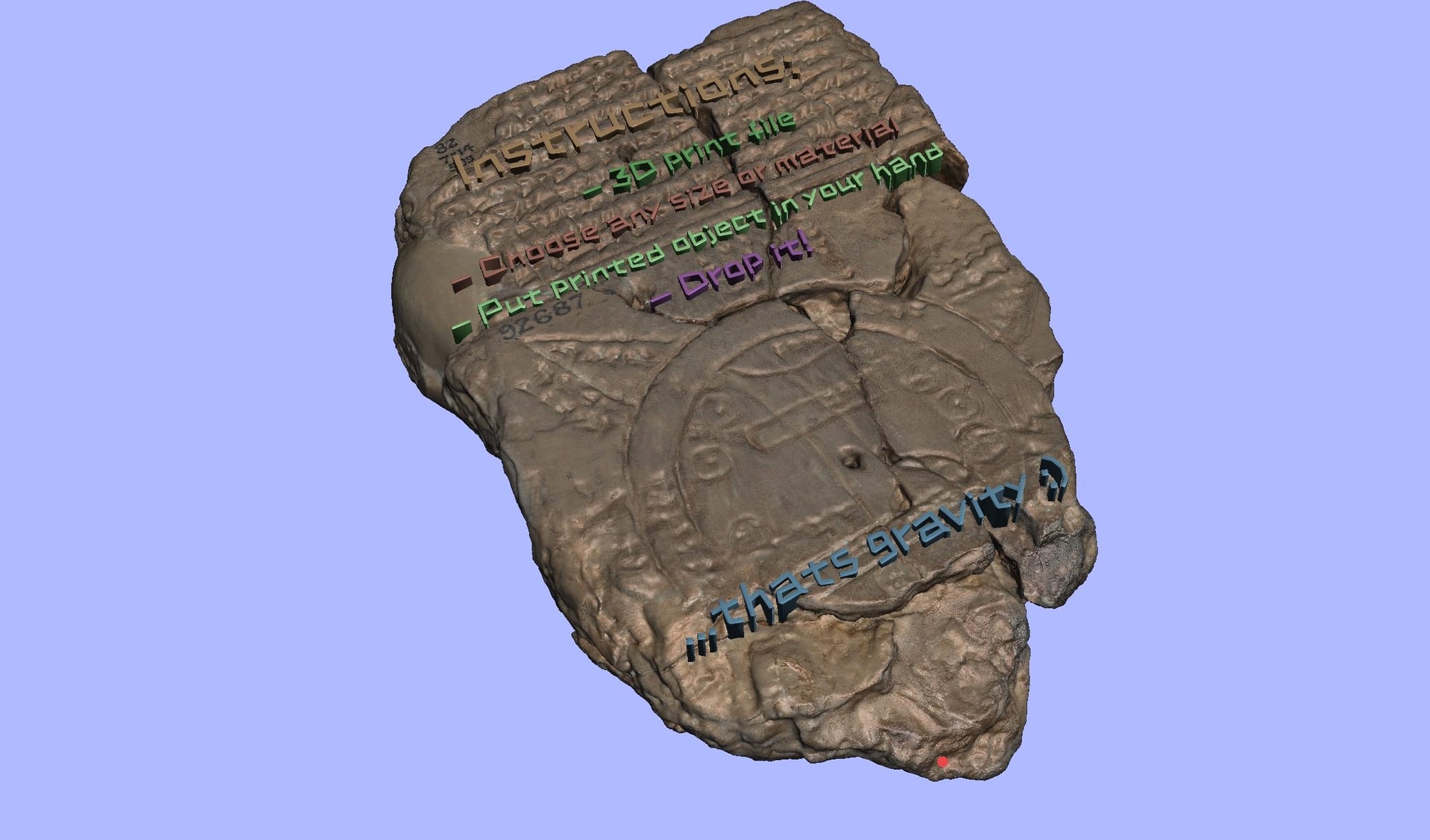

Nora Al-Badri, a Berlin-based artist known for her incisive critiques of cultural imperialism and data colonialism, addresses these issues head-on. In her project Spherical Drop, she engages with digitized cultural heritage through speculative AI-generated reconstructions. The work remixes the ancient “Babylonian Map of the World” and transforms it into a digital sculpture, later sold as an NFT—with proceeds supporting refugee rights initiatives. Al-Badri doesn’t just critique the theft of physical artifacts; she turns the dataset itself into a contested terrain. Her work reframes the training set as a site of violence and reclamation, challenging the legitimacy of algorithmic systems built on inherited visual regimes and unequal data access.

Artist-Led Interventions into Opaque AI Systems

Creative AI often hides behind layers of abstraction—neural networks, training sets, model weights—all of which obscure how decisions are made or whose labor is being leveraged. For British artist and technologist James Bridle, this opacity is not just a technical flaw, but a systemic one. Bridle’s work seeks to make visible the hidden infrastructures of technology, from server farms to surveillance networks.

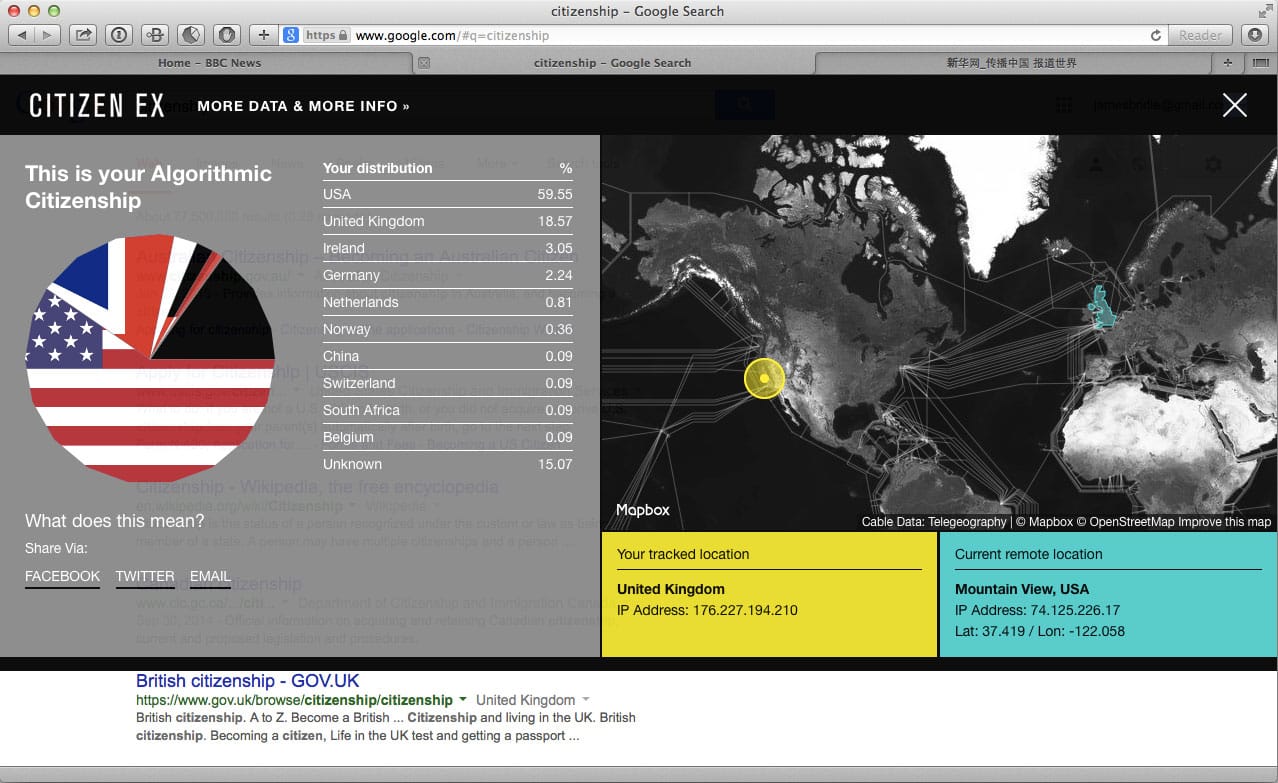

In “New Dark Age: Technology and the End of the Future,” Bridle writes: “We live in a world of systems that are too complex to understand.” His art, including the open-source project Citizen Ex, which maps how users' online activity is tracked across legal jurisdictions, exposes how digital systems quietly redraw the borders of identity and control. For Bridle, algorithmic literacy is not optional. It’s a precondition for digital rights.

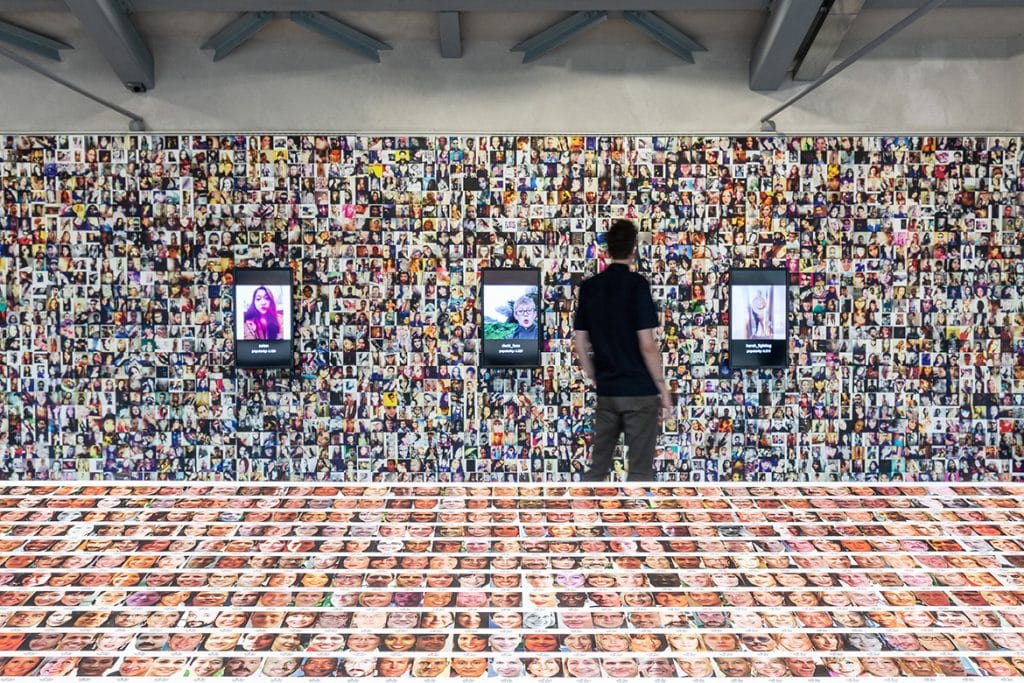

In parallel, Trevor Paglen has spent years documenting the visual language of surveillance—undersea cables, spy satellites, and facial recognition datasets. His project ImageNet Roulette, developed in collaboration with Kate Crawford, revealed the racist, sexist, and violent labels embedded in widely used AI training sets. It briefly went viral before being pulled offline, not because it failed, but because it succeeded too well. Paglen’s practice reveals that algorithmic bias is not an aberration; it’s an artifact of the values embedded in data collection, classification, and computation.

Toward Data Autonomy and Algorithmic Accountability

Digital sovereignty is not merely a matter of governance—it is a creative imperative. As AI reshapes the boundaries of expression, artists are reclaiming tools of automation not to aestheticize them, but to dismantle and repurpose them. This emerging cohort isn’t interested in mimicking human creativity; they are interrogating its very substrates.

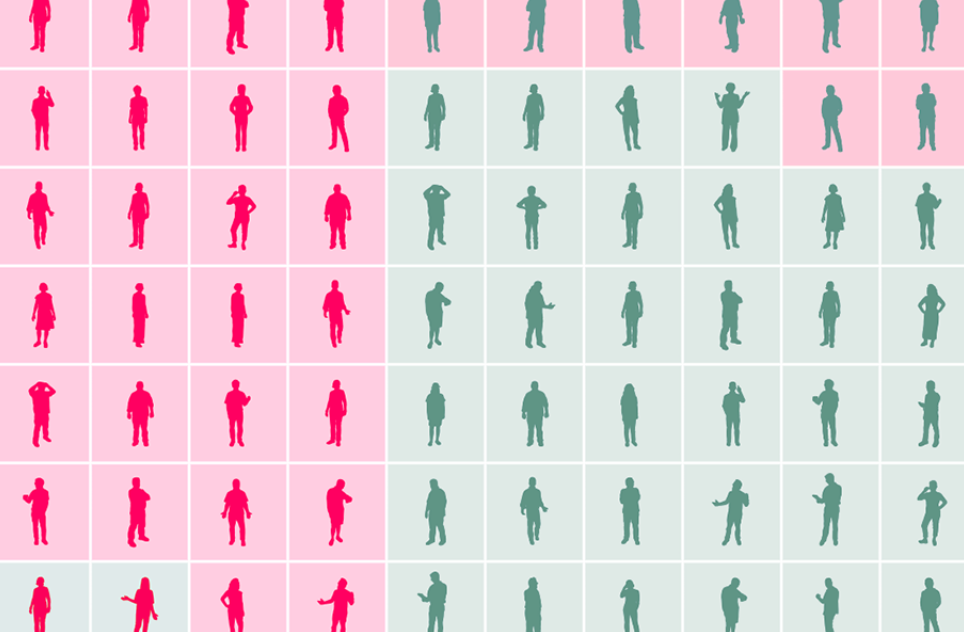

At the forefront of this shift is Spawning AI, a company founded by artists and technologists Jordan Meyer and Mathew Dryhurst. Spawning seeks to empower creators by giving them control over how their work is used in AI training datasets—often scraped without consent. Their tools embody the principle of data autonomy, the right to curate, manage, and restrict the use of one’s digital traces. Key initiatives include:

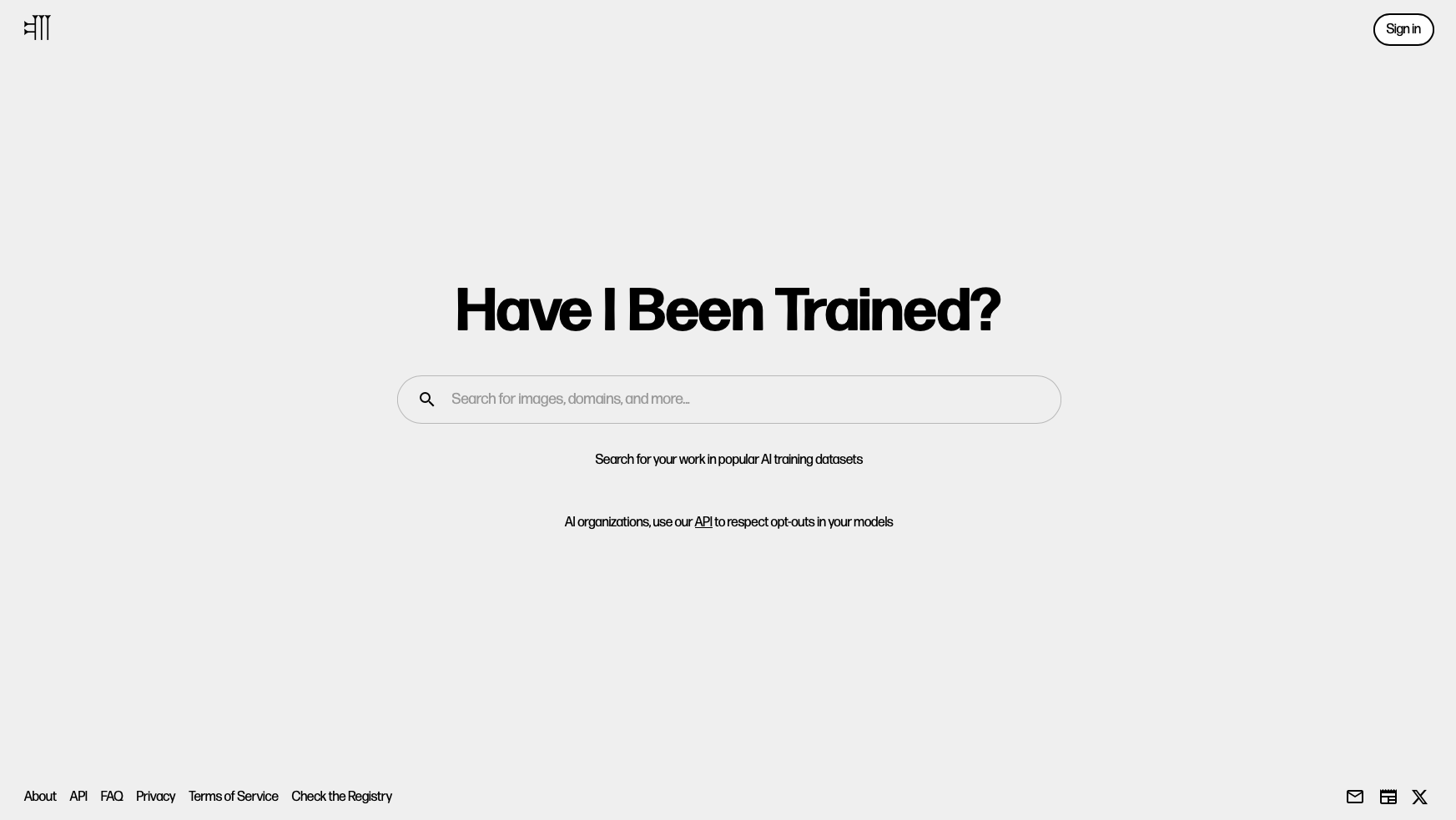

- Have I Been Trained?, a searchable interface that allows artists to determine whether their works appear in major datasets like LAION-5B.

- The Do Not Train Registry, which enables creators to opt out of inclusion in future training sets.

- A curated dataset of nearly 40 million public domain and Creative Commons–licensed images, designed for ethical AI training, where artists can opt in and receive compensation for participation.

Spawning AI and broader efforts like the Data Union initiative signal a fundamental change in how creative labor is valued and protected in machine learning ecosystems. These projects are not only technical interventions—they are cultural tools that reframe consent and authorship in the age of algorithmic reproduction. Yet real change will require more than opt-outs. It will demand new infrastructures, inclusive platforms, and public discourse that centers digital rights as foundational—not peripheral—to the future of AI. Artists, activists, and technologists must work together to ensure that algorithmic systems are not just efficient, but just.

The New Aesthetic of Control

Control is no longer just about access; it's about legibility. What we cannot see, we cannot contest. The aesthetic of control emerging from today’s most critical AI-driven works is one of exposure—not just of systems, but of ideologies embedded in code. Whether it’s Al-Badri’s algorithmic hauntologies, Bridle’s infrastructural illuminations, or Paglen’s visual forensics, each challenges the premise that technology is neutral or inevitable. They remind us that every dataset is a worldview, every algorithm a policy, and every AI-generated image a contested artifact.

As generative systems become more enmeshed in design, storytelling, and social infrastructure, the question isn’t whether AI will be creative. It already is. The question is: who defines its ethics, who authors its outputs, and who benefits from its proliferation? Digital sovereignty isn't just a policy issue. It’s a cultural one. And in the hands of artists, it becomes a tool for imagining—and insisting on—futures where creativity is not subsumed by automation, but strengthened through autonomy.