The future of creative AI isn’t flat. It’s three-dimensional, kinetic, and streaked with graphite. While image-generating algorithms dominate headlines, another modality is gaining traction in studios, labs, and exhibition spaces: robots that draw—not with pixels or prompts, but with arms, sensors, and ink. These machines operate in real time and real space. They move through error, pressure, and resistance. They listen, hesitate, improvise.

This isn’t about simulating creativity. It’s about redefining it through embodiment—where intelligence is expressed not just in computation, but in physical action.

Drawing as Performance

The idea of a machine making art without human input began with Harold Cohen’s AARON, a rule-based system that generated autonomous drawings from the 1970s onward. AARON was groundbreaking—not for its interactivity, but for its insistence on internal logic. Its visual output evolved, but its process was sealed. It did not listen. It did not respond. What AARON demonstrated, however, was that creative behavior could be encoded, systematized, and endlessly iterated.

But as robotic systems gained bodies—arms, sensors, mechanical joints—the question shifted: what if machines could draw not just from rules, but from interaction?

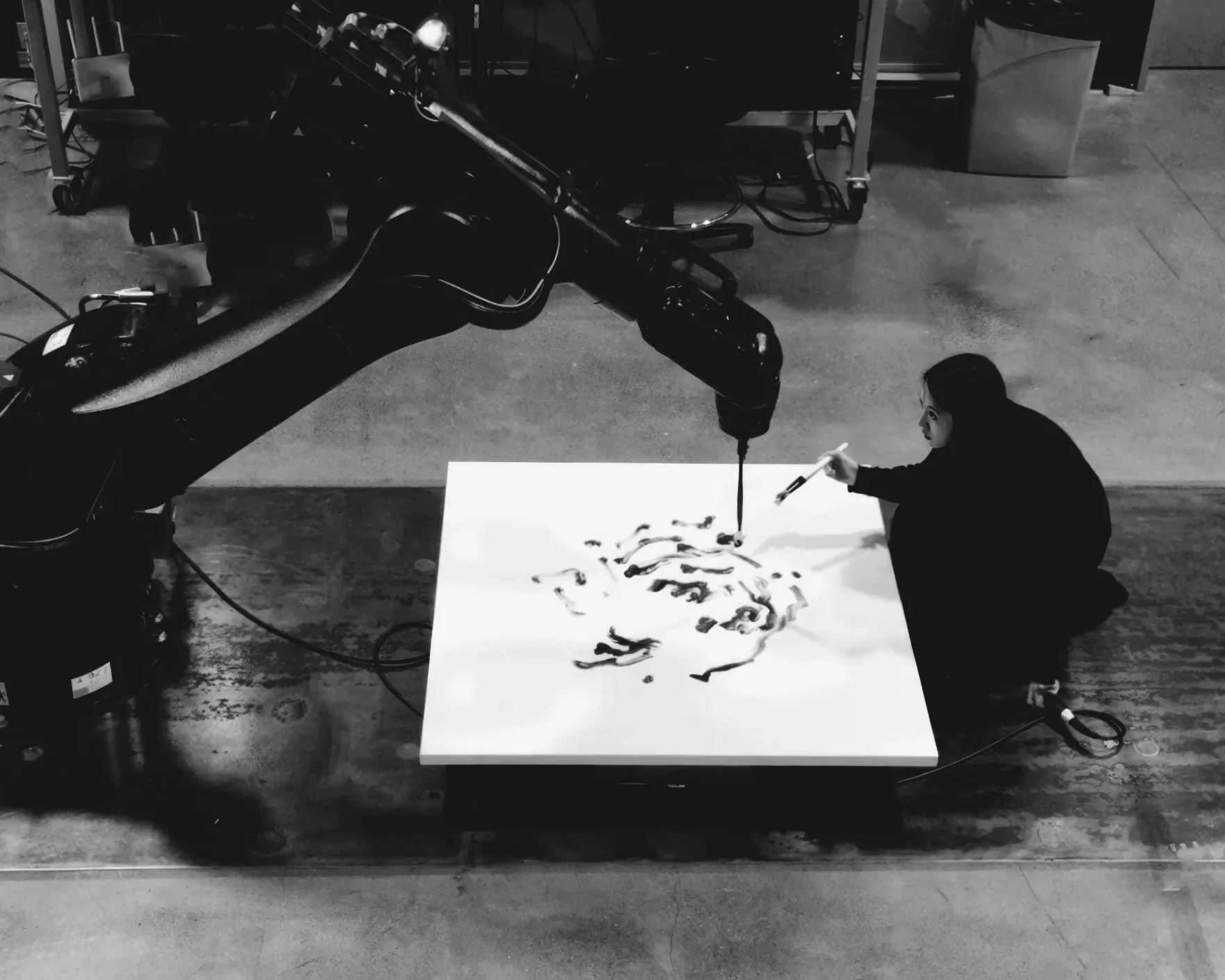

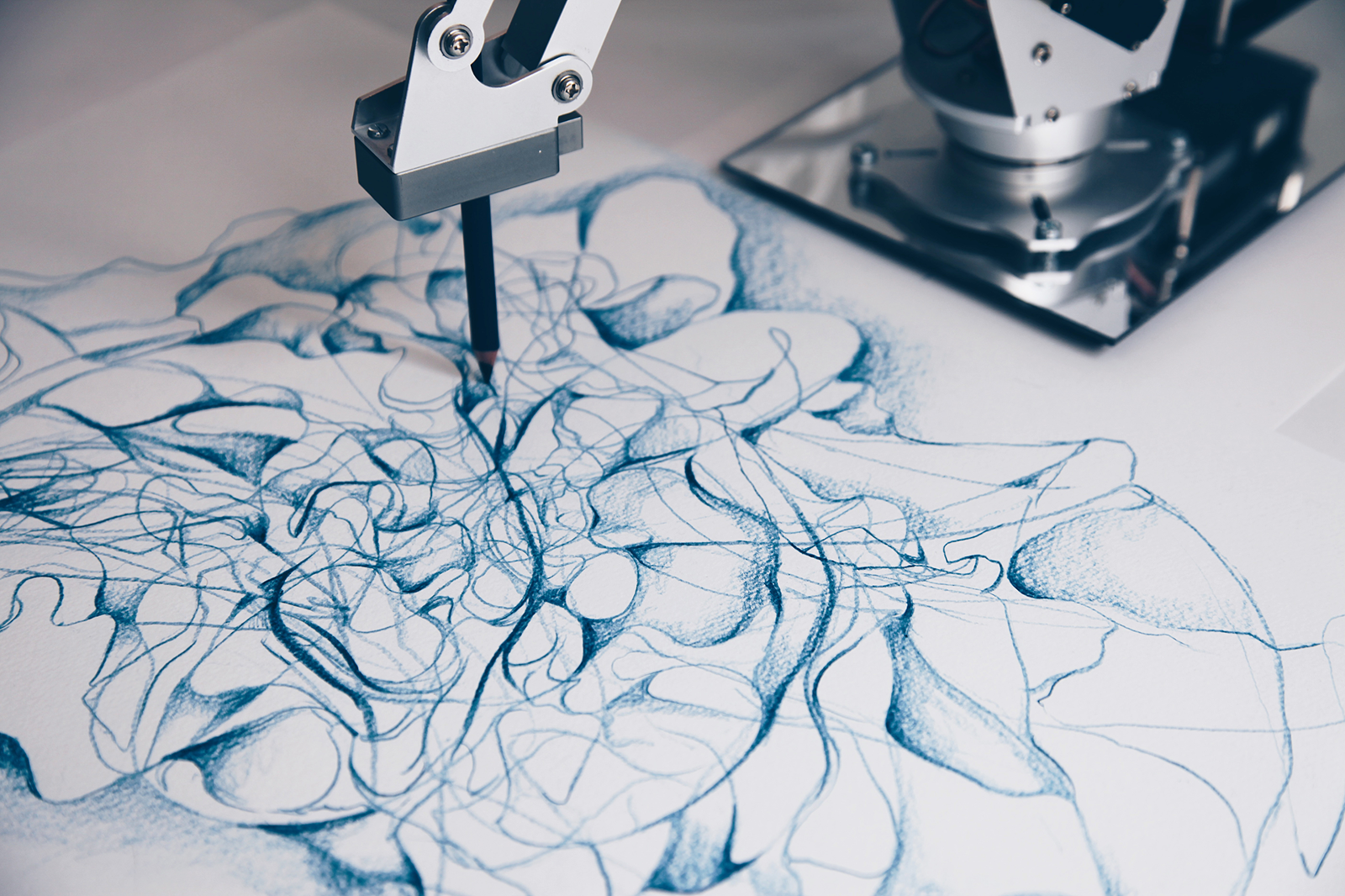

Sougwen Chung’s Drawing Operations (2015-2018) takes that leap. Her robotic collaborators are trained on data from her own hand-drawn lines, but during live performances, they work with her—not for her. The robot anticipates and reacts in real time, generating an unfolding duet between human and machine. It’s an act of co-authorship, where drawing becomes performance, and agency is distributed across biological and mechanical bodies.

The leap from AARON to Chung marks a shift in creative AI—from symbolic systems that reason about form to embodied systems that engage in gesture. If Chung’s performances reflect shared authorship, what happens when machines respond not just to humans, but to the world around them?

Sensing, Motion, and Machine Perception in Robotic Drawing

While Chung’s robots co-create in performance, other artists explore embodiment through constraint, feedback, and environmental response. These systems don’t simulate cognition—they translate limited perception into expressive motion. Sound, friction, or simple algorithms become drivers of physical mark-making.

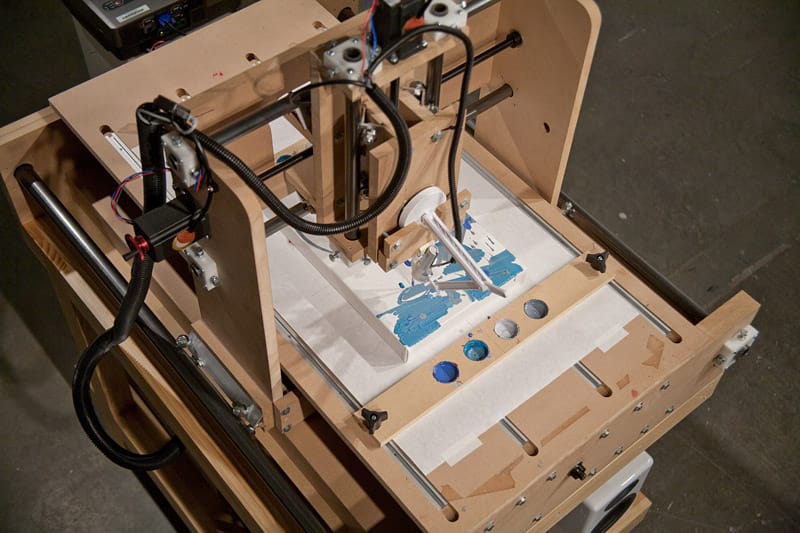

Benjamin Grosser’s Interactive Robotic Painting Machine (2011) exemplifies this reactive mode. Built without AI, the system uses microphones and servo motors to respond to ambient sound. A crowded room results in chaotic, sweeping brushstrokes; quiet environments yield more tentative gestures. The machine becomes a kind of sensory conduit—translating audio energy into painterly movement. The drawings themselves are unpredictable, sometimes lyrical, sometimes erratic. Grosser’s robot isn’t intelligent in a computational sense, but it’s unmistakably engaged—a reactive body in dialogue with its environment.

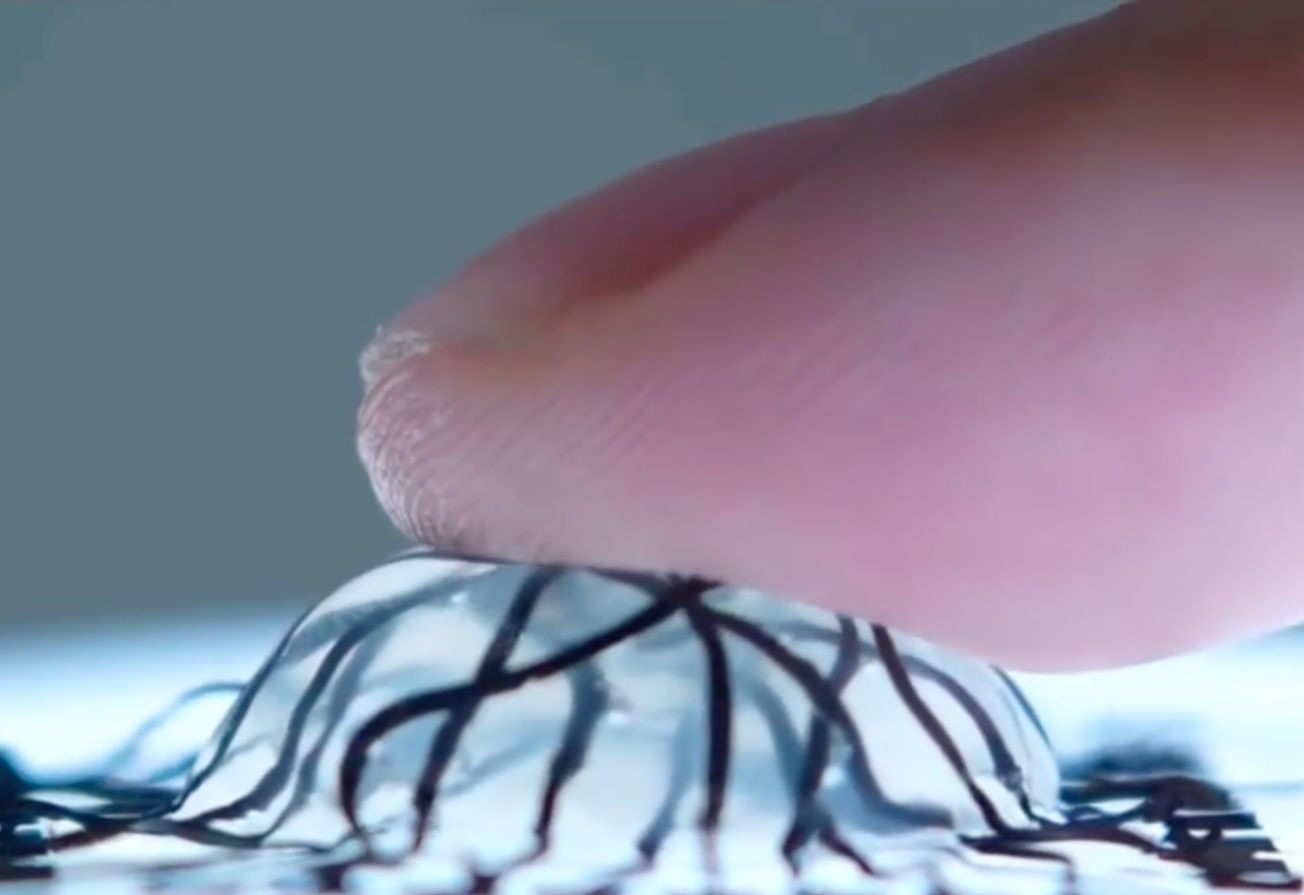

Diana Lange’s Drawing Machine series offers a more introspective variation on embodied generativity. Her analog systems—built from custom-milled parts, pendulums, and motors—create evolving, hypnotic compositions through loops of movement and mechanical friction. Rather than simulate perception, Lange’s work foregrounds material constraint and procedural rhythm. The machines don’t perceive, but they embody—marking time with each rotation, and producing drawings that feel meditative, even intimate. Her practice reminds us that expression doesn’t require sentience or AI; it can emerge from the hum of a motor and the tension of a pen against paper. Where Grosser’s robot listens, Lange’s machines hum in ritual loops. They don’t interpret data—they reveal how system architecture itself can become a creative force.

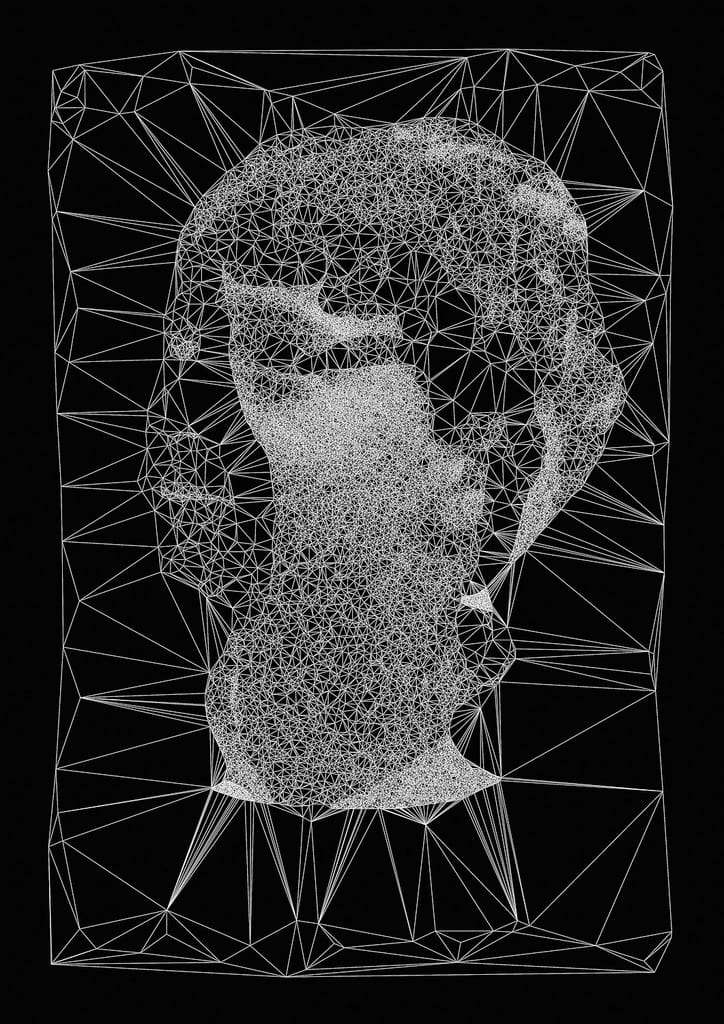

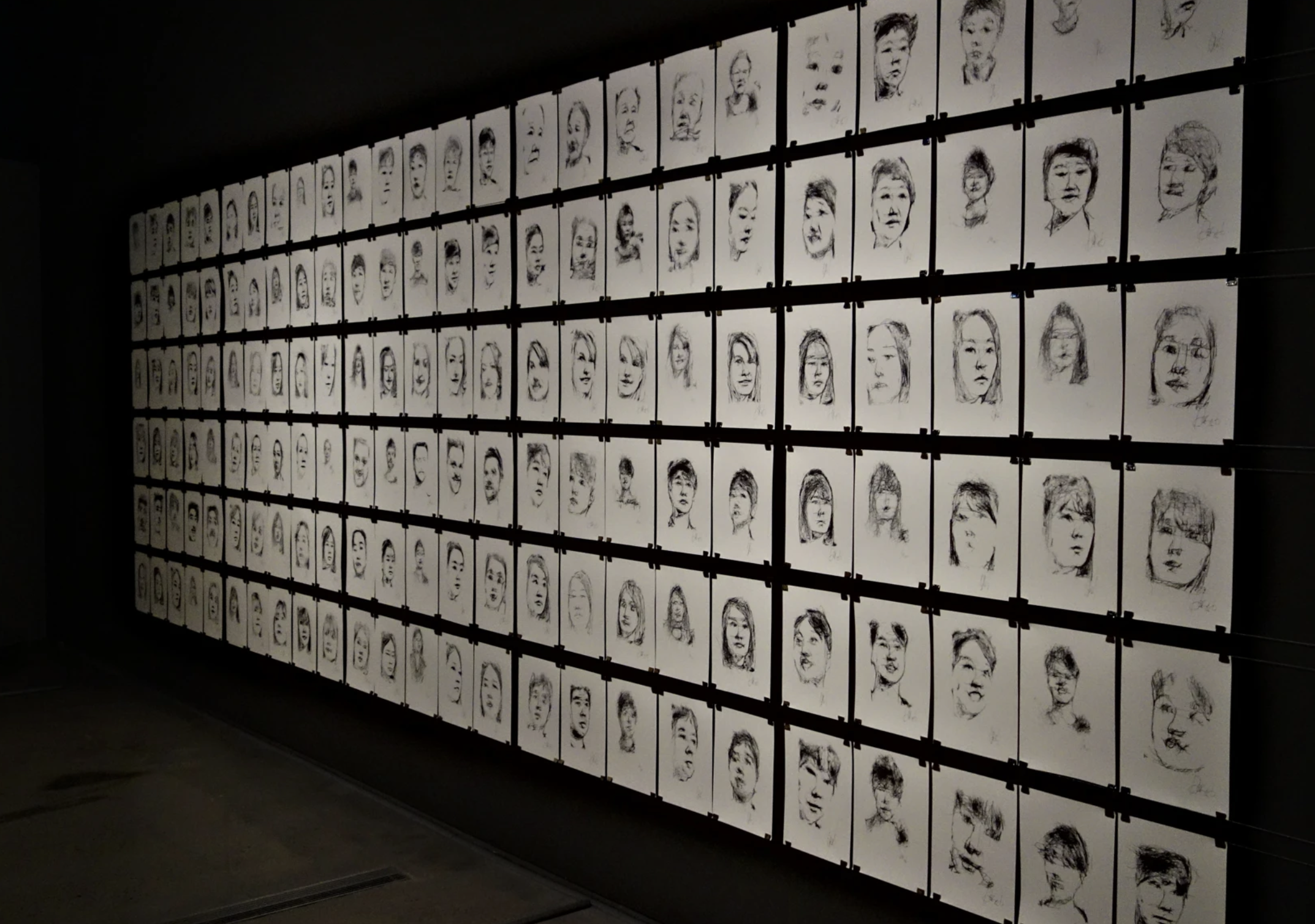

Patrick Tresset’s robotic draftsmen, in his Human Study series (2011-2024), meanwhile, reintroduce the human subject—not through collaboration but observation. His installations feature robotic arms equipped with cameras and behavioral algorithms that sketch portraits of live sitters. Guided by rules, randomness, and minimal perception—not deep learning—their behavior feels uncannily human. They hesitate, recalibrate, and drift off-course in ways that echo the distractions of a human hand. Tresset’s robots don’t chase perfection; they pursue presence.

Together, Grosser, Lange, and Tresset map a continuum of machine awareness: from reactive to ritualistic to observational. Each project bypasses the polished aesthetics of generative AI and returns us to something more grounded, more mechanical, more vulnerable. In doing so, they expand our understanding of what it means for a machine not just to draw, but to sense, to move, and to express.

Robotic Presence as Artistic Gesture

If Grosser, Lange, and Tresset explore how robots draw through interaction constraint, or perception, a new wave of artists reframes drawing altogether—not as mark-making, but as gesture performed in space. In these works, the line disappears, but the principles of embodied drawing—movement, responsiveness, and intentionality—persist.

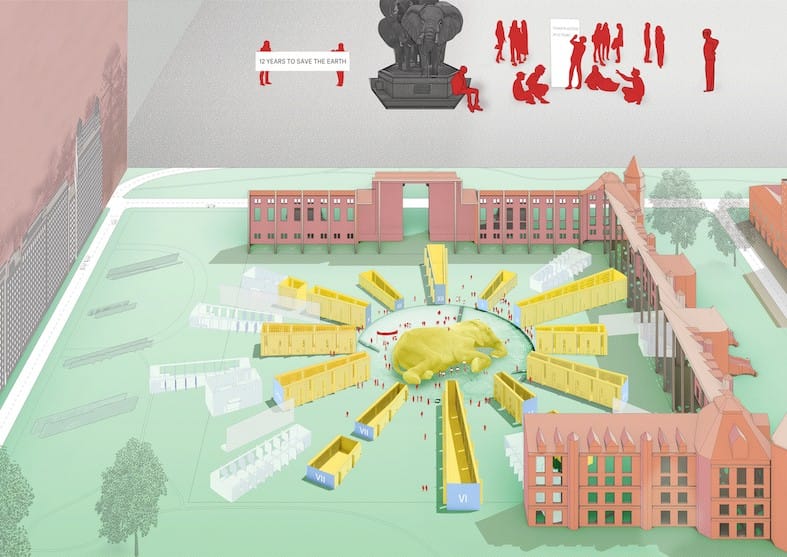

Madeline Gannon’s Manus (2018) expands the idea of robotic drawing to an architectural scale. Ten towering industrial robot arms, each programmed with custom behavioral software and proximity sensors, form a reactive robotic ecology. As viewers enter the space, the machines shift—turning, arching, leaning in or retreating. Some act curious; others are shy. No marks are made, yet each gesture feels choreographed. Gannon doesn’t just engineer responsiveness—she choreographs relational dynamics, drawing viewers into a tactile conversation with robotic presence.

This reframing—machine as performer rather than instrument—was seen in an early 2008 project by Golan Levin, Double-Taker (Snout). A single robotic arm, capped with oversized googly eyes, uses face-detection software to react to passersby with comedic timing. It performs glances, double takes, and prolonged stares. The effect is ridiculous and uncanny—turning passive surveillance into a study in nonverbal expression. Levin’s machine doesn’t draw, but it communicates with clarity, absurdity, and affect.

Gannon and Levin shift the emphasis from drawing as output to embodied behavior as communication. Their machines echo the gestures of mark-making—the arc of a glance, the tension of proximity—without ever touching paper. They remind us that drawing is not only about surface and medium, but also about presence and intention.

These installations challenge the assumption that robotic art must be about control, replication, or simulation. Instead, they create new forms of embodied interaction, where meaning arises from movement, timing, and space. In these works, the robot becomes not a tool—but a co-performer, an observer, and a collaborator in shaping perception.

The Future of Machine Drawing Is Physical, Not Virtual

The thread that connects AARON’s algorithmic autonomy to Chung’s live co-creation, Grosser’s sonic responsiveness, Lange’s procedural rhythm, Tresset’s observational stylization, and the behavioral choreography of Manus and Snout is embodied intelligence. In each case, drawing isn’t the product of static code or cloud-based computation—it’s the result of motion, materiality, context, and feedback.

These machines don’t just redraw the boundaries of art—they reframe creativity itself as embodied computation. They introduce constraint. They invite error. They amplify nuance. The machine doesn’t just simulate drawing—it experiencesit, through torque, tension, hesitation, and weight.

As artists and engineers continue to develop embodied creative systems, drawing machines offer more than spectacle. They offer a testbed for co-creative intelligence, where expression is grounded not in abstraction, but in the physical world—ink on paper, gesture in air, line in motion.

In redefining what it means to draw, these systems are also redefining what it means to think, to feel, and to create—through machines that move like artists.