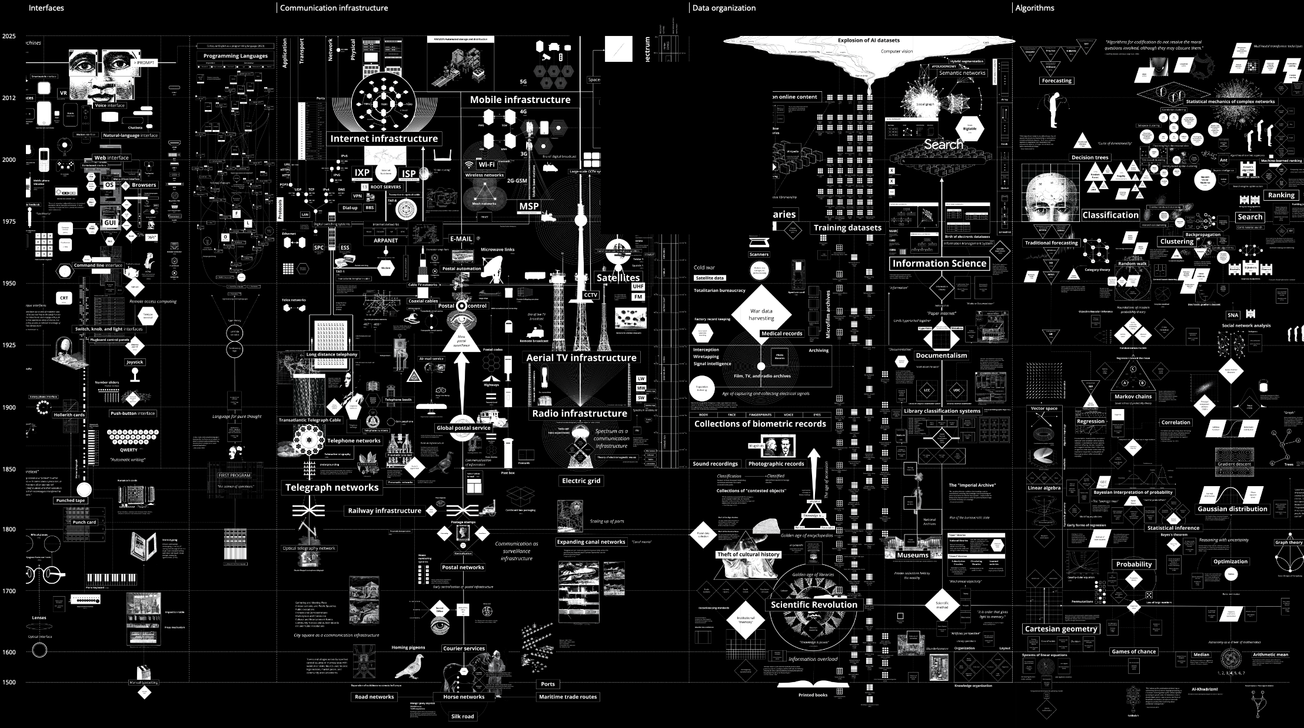

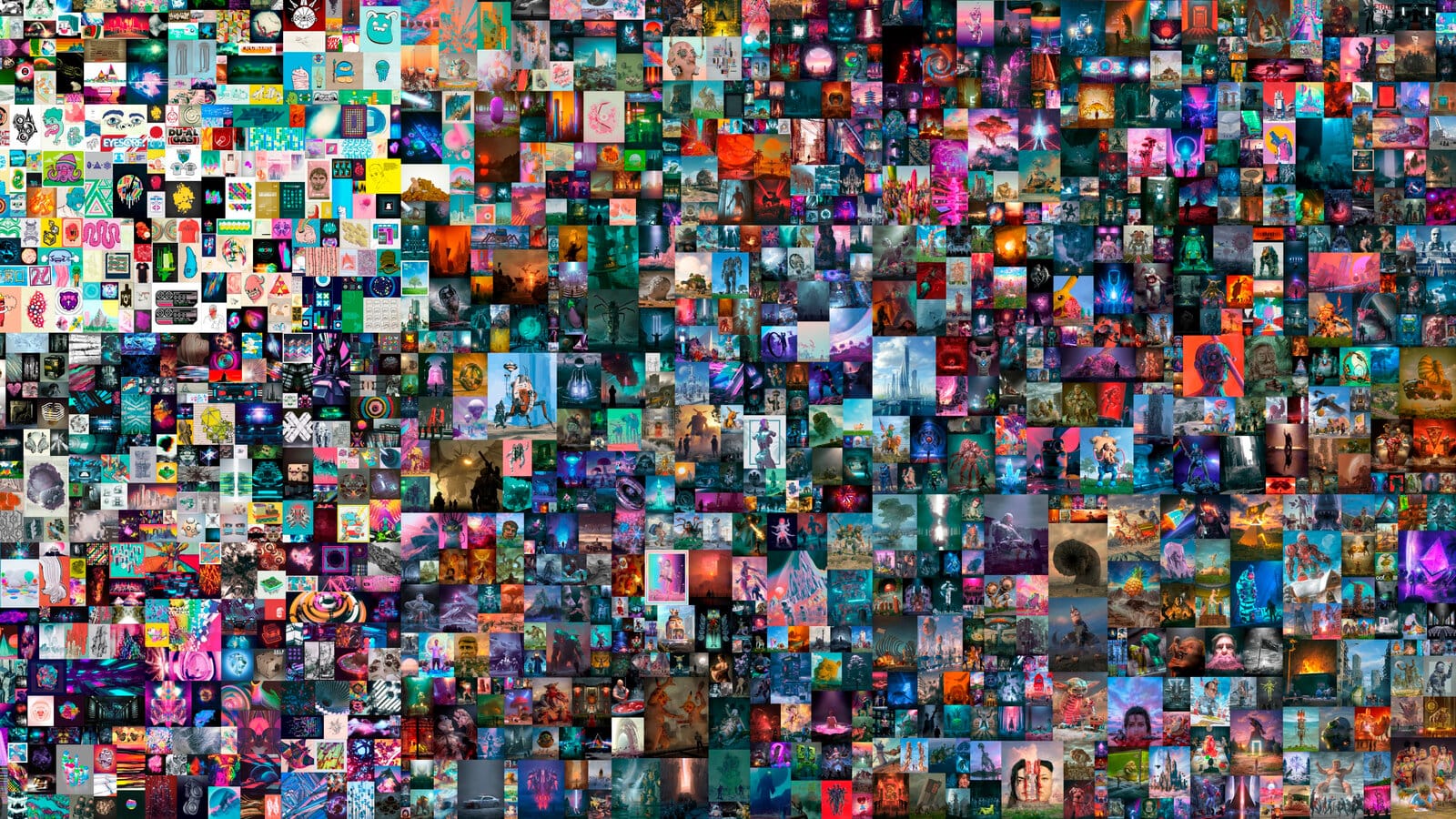

Crypto art’s post-boom phase is producing more than abandoned Discords. It’s generating digital waste, artistic critique, and a reckoning with infrastructure. When Beeple sold a $69 million JPEG at Christie’s in 2021, it wasn’t just a record-breaking art sale—it was a turning point for the internet. NFTs promised creative freedom, decentralized markets, and ownership redefined. But while headlines celebrated the future of digital assets, the energy bills were quietly mounting.

The blockchain never forgets, but it leaves a mess. Every NFT minted during the boom is backed by hardware, electricity, and server time—most of which don’t age gracefully. What’s left behind is a growing pile of digital detritus: burned-out GPUs, shuttered mining farms, and thousands of orphaned tokens floating in the blockchain like abandoned shopping carts.

What Happens After the Mint?

The early days of NFTs ran mostly on Ethereum’s proof-of-work (PoW) system, a consensus mechanism that verified transactions using brute computational force. PoW is notoriously energy-hungry, often compared to the carbon footprint of entire countries. In 2022, Ethereum shifted to proof-of-stake (PoS), a method that requires far less electricity by validating transactions through staked tokens rather than computation. The Ethereum Foundation claims this transition reduced energy use by over 99%.

That’s a meaningful win—but it doesn’t erase the legacy infrastructure. Mining rigs built for the PoW era are being decommissioned en masse. On resale sites like eBay and Alibaba, used GPUs are flooding the market. Some crypto farms in Inner Mongolia and Kazakhstan have simply been abandoned, leaving behind ghost data centers and e-waste in their wake.

Artists Mine the Wreckage

With the speculative fervor cooling, some artists are shifting focus—from chasing the next mint to interrogating what’s already rotting. Sarah Friend’s Lifeforms flips the idea of digital permanence on its head. The project consists of NFTs that “die” unless they’re transferred to someone else within a fixed time window. Ownership becomes a shared responsibility, not a static endpoint.

Berlin-based conceptual artist Harm van den Dorpel explores similar tensions in Mutant Garden Seeder, a series of generative NFTs launched on Folia. Each piece is produced by a unique algorithmic seed, making every token a mutation in a digital garden. While the project doesn’t explicitly engage with environmental data, it resists the static notion of the collectible, favoring time-based variation and process over fixed form.

Everest Pipkin, a media artist and toolmaker, creates speculative ecological fictions from discarded technologies. While their Barnacle Goose Experiment doesn’t directly address NFTs, their body of work frequently critiques the extractive logic of tech infrastructures. Pipkin’s research blends cartography, folklore, and networked systems—turning dead hardware into sites of imagined ecology.

Meanwhile, the Residual Media Depot at Concordia University collects and catalogs obsolete tech: mining rigs, hard drives, magnetic media. Their work—part media archaeology, part digital anthropology—treats crypto waste not as failed tech, but as a cultural artifact of economic speculation.

Beyond Art: Infrastructure as Critique

Not all artists are working within blockchain. Some are stepping outside it entirely to critique the digital economy it reflects. In Terms of Service, Constant Dullaart manipulated thousands of fake social media accounts to redistribute influence and attention. The project exposed the invisible labor behind value in digital spaces—an economy where engagement, not substance, determines worth. It’s not an NFT piece, but the logic is familiar: synthetic scarcity, viral momentum, and platform dependency.

Others are designing more sustainable systems from the ground up. Teia, an open-source NFT platform built on the energy-efficient Tezos blockchain, emphasizes community governance and slower, intentional curation. Zora, a protocol on Ethereum’s Optimism Layer 2, lowers gas costs and reduces emissions while allowing creators to mint and sell directly. And on the infrastructure side, Filecoin Green is trying to make blockchain emissions legible. It tracks the energy consumption of storage providers, pushing for on-chain verification of carbon offsets. It’s not a perfect solution, but it’s a step toward transparency.

From Scarcity to Circularity

The early NFT boom was built on a simple equation: scarcity = value. But that formula is starting to collapse under environmental, economic, and conceptual pressure. Artists and developers are beginning to imagine systems where value isn’t hoarded, but redistributed, where infrastructure isn’t invisible, but interrogated.

“Recycling” an NFT may sound like a punchline—these tokens are immutable by design—but the metaphor sticks. Blockchain assets might not biodegrade, but they can decay conceptually. And that decay is becoming raw material for a new kind of digital practice: one that favors stewardship over speculation, entropy over eternity. As the blockchain slows and the carbon accounting begins, the most radical move for digital creators may be to let go of permanence—and start designing for decomposition.