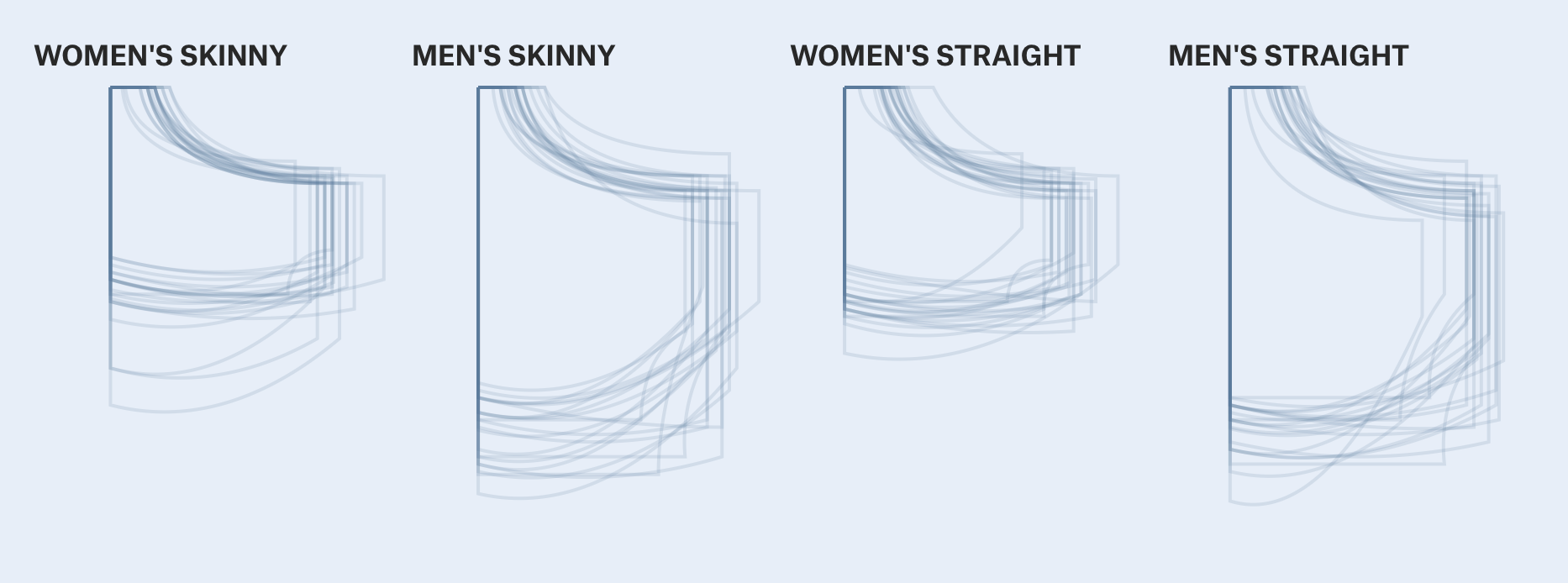

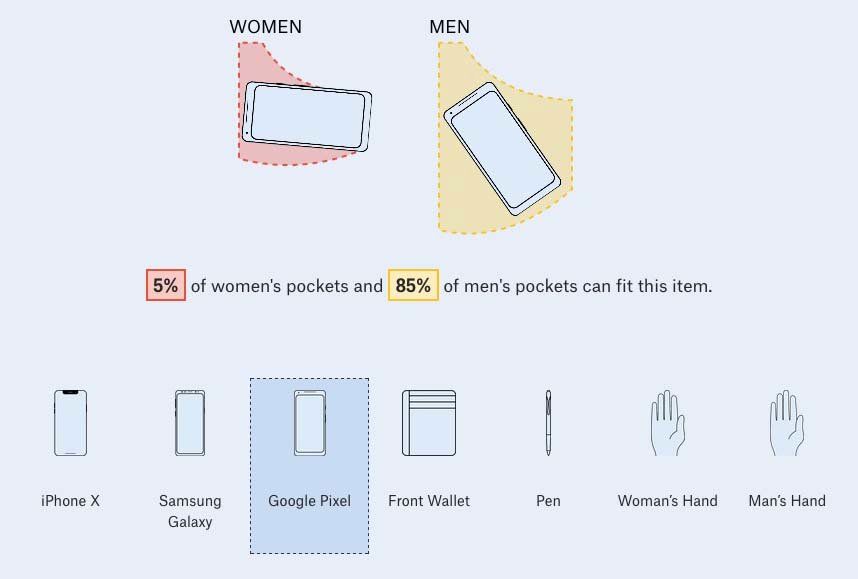

How do we understand the value of the creator’s hand and its influence in shaping our design choices, beliefs, behaviors, interactions, and social and cultural conceptions? Through the lens of discursive and inclusive design, we can unpack and explore the social and cultural constructs of an object’s design, materiality, technology, and functionality—for example, the design of pockets in women’s jeans. The standard front pocket on a pair of women’s jeans in the 20th century had limited utilitarian functionality due to their size. Unlike typical male jeans, women’s jeans were typically fitted to the body, and the pockets were shallow, with little room to hold any object. Yet, as a signifier, they had significant functionality. The pocket served as a signifier of the intended user’s gender.

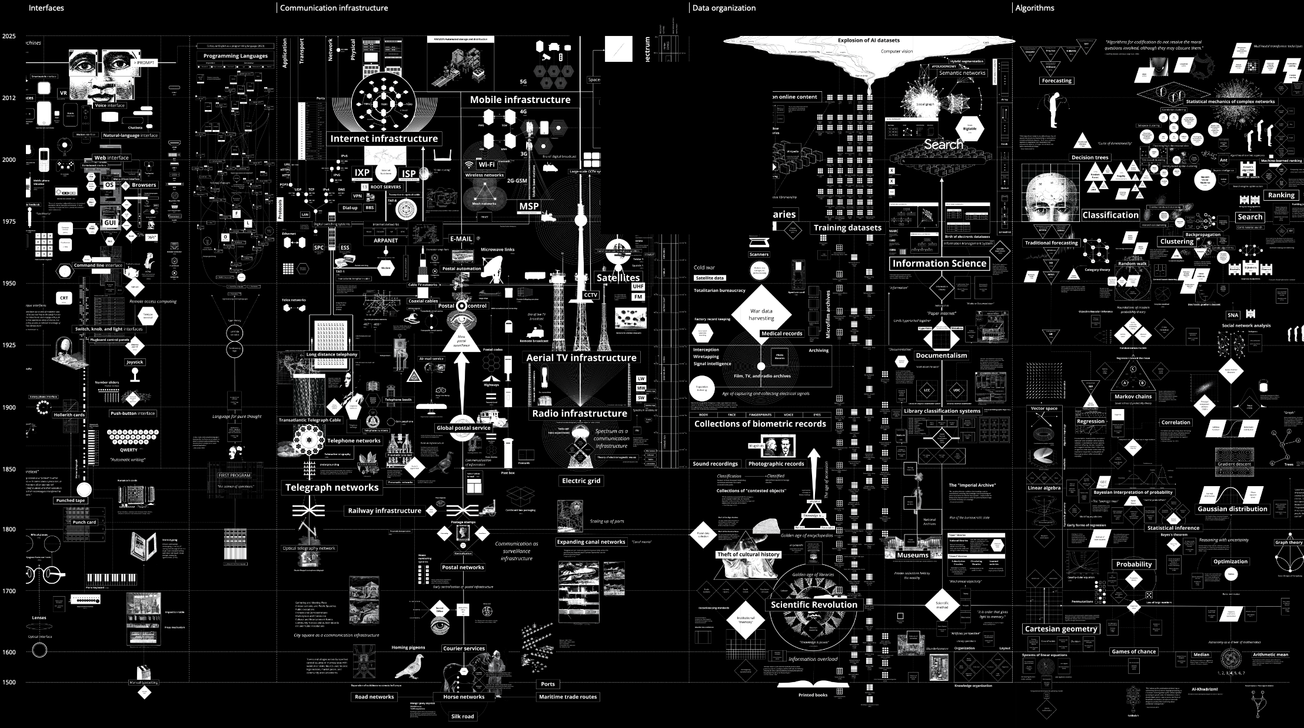

Rather than unpacking the object to explore and understand the social or cultural construct underpinning the design of pockets, as would be done in critical and discursive design practice, it may be useful to focus attention on the creator, the designer. How is the lived experience, cultural background, and identity of the creator informing their design, engineering, and technological innovations?

Industries in design and technology have a hetero-normative, white, male, able-bodied, privileged hierarchy. Both designers and technologists strive to understand and respond to user needs and experiences while mitigating their own potential biases. However, deeply rooted structural biases and systemic inequalities are pervasive and shape the systems within which design and technology function. As a result, it is the hetero-normative, white, male power structure that remains invisibly visible—a central challenge for inclusive design and accessibility-focused innovation.

Would, for example, a person who has experienced oppression propose design or technological innovations in the same manner as someone who has not? Would a person who lives in fear of being shot—whether because they are a person of color, grocery shopping, or a child or teacher in an elementary school—have different needs in the functionality of a desk, a smartphone, or a critical piece of software on that smartphone? These questions are essential in the social impact of design and human-centered technology development.

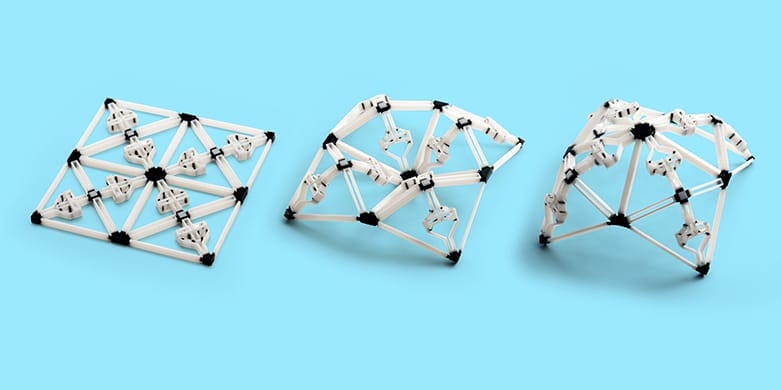

There is immense value in bringing the unique voice, perspective, and background of the designer to the forefront of design thinking as a practice. Placing increased value on such diversity will result in a richer tapestry of innovative solutions, products, and experiences that not only cater to a broader spectrum of human needs and desires but also challenge the status quo. In doing so, we can drive forward a more inclusive and progressive evolution of design—one that is grounded in cultural diversity, equity, and representation while fostering creativity and speculative design approaches that reimagine our collective future.