At the turn of the twentieth century, as much of the world was recovering from World War II and wealthy, primarily colonial nations were experiencing an intoxicating infusion of technology in their daily lives, an exploration into technologies and systems of information, the “control and communication in animal and machine” was emerging. During this period, three distinct threads in discourse began to intersect – communication theory, computational technologies, and creative processes in Fluxus informed by post-structuralism.

In 1948, amidst the Macy Conferences (1946 to 1953), Norbert Wiener, widely considered the originator of cybernetics, published 'Cybernetics: Or Control and Communication in the Animal and the Machine,' in which he describes the emerging territory of cybernetics as “the study of what in a human context is sometimes loosely described as thinking and in engineering is known as control and communication. In other words, cybernetics attempts to find the common elements in the functioning of automatic machines and of the human nervous system, and to develop a theory which will cover the entire field of control and communication in machines and in living organisms.” Central to Weiner’s concern was the relationship between the message and the response, albeit with humans or machines.

“When I communicate with another person, I impart a message to him, and when he communicates back with me he returns a related message which contains information primarily accessible to him and not to me… When I give an order to a machine, the situation is not essentially different from that which arises when I give an order to a person. In other words, as far as my consciousness goes I am aware of the order that has gone out and of the signal of compliance that has come back. To me personally, the fact that the signal in its intermediate stages has gone through a machine rather than through a person is irrelevant and does not in any case greatly change my relation to the signal. Thus the theory of control in engineering, whether human or animal or mechanical, is a chapter in the theory of messages.” – NORBERT WIENER

Computational Tech

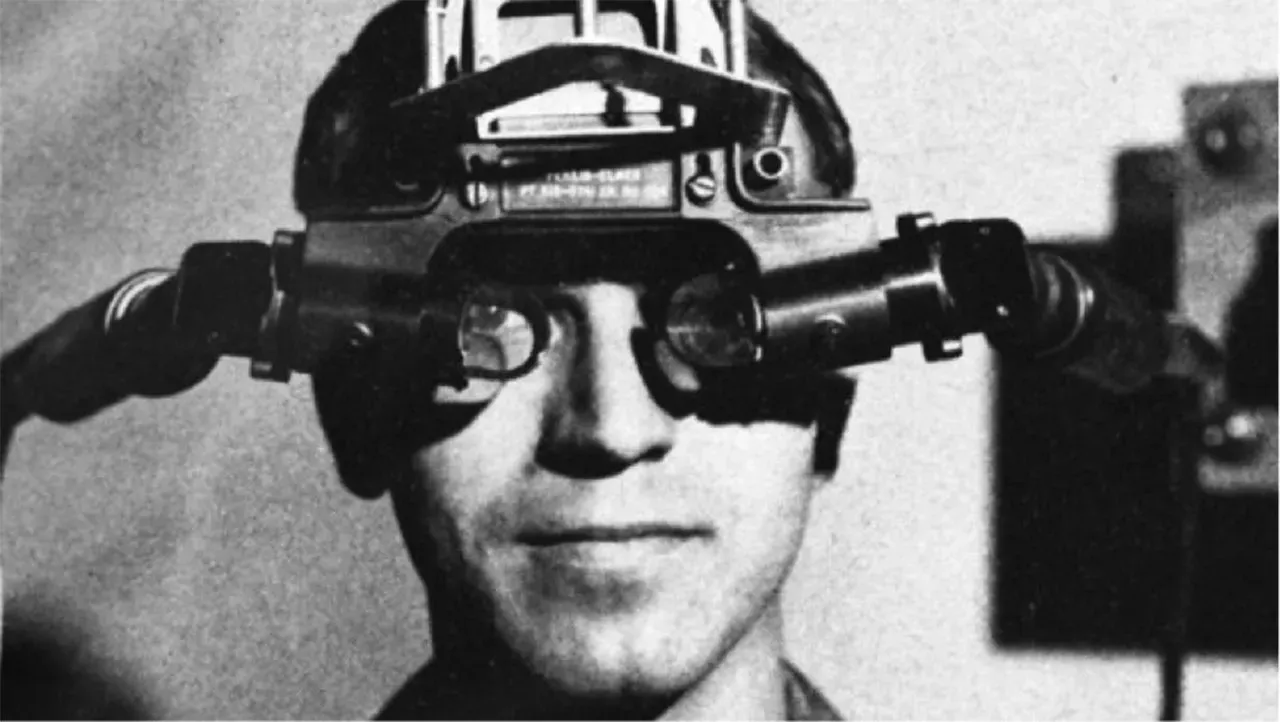

Ivan Sutherland, former doctoral supervisee of Claude Shannon, the pioneering computer scientist and a key participant in the Macy Conferences, invented the Sketchpad and the Head Mounted Display (HMD) in 1963 and 1965 respectively. These seminal inventions were not simply precursors to a range of software and hardware inventions from CAD to virtual reality but pioneered computer vision and human-computer interfacing at-large.

Describing the potential of the HMD Sutherland states “A display connected to a digital computer gives us a chance to gain familiarity with concepts not realizable in the physical world. It is a looking glass into a mathematical wonderland.” During this same period, Douglas Engelbart invented the computer mouse (1963), and shortly after, Alan Kay invented the Dynabook (1968), the precursor to the personal laptop. According to Kay, “[…] computational media environment[s] in general, regardless of the size of a form of device in which it is implemented – should support viewing, creating and editing all possible media which have traditionally been used for human expression and communication.”

Fluxus and post-structuralism

The advent of post-structuralism, with a convergence of theories developed by Derrida, McLuhan, Barthes, Deleuze, Lyotard, Foucault, and Kristeva, amongst others, meaning began to be understood as not fixed or dependent on the intention of the author.

“There is no more fiction that life could possibly confront, even victoriously-it is reality itself that disappears utterly in the game of reality-radical disenchantment, the cool and cybernetic phase following the hot stage of fantasy.”– MARSHALL MCLUHAN

Fluxus, characterized by founder Maciunas to “promote a revolutionary flood and tide in art, promote living art, anti-art.” Seminal artists and activities contributing to this movement include Joseph Beuys, George Brecht, Yoko Ono, Dick Higgins, Alison Knowles, Wolf Vostell, and Nam June Paik – amongst many others. Reconsidering the role of art in society, many works often involved audience participation, indeterminacy, and interaction. These elements would become key elements in future creative computational works and explorations.

Early works bridging and intersecting cybernetics, computational tools and technologies, and creative processes informed by post-structuralism include Roy Ascott, Myron Kruger, David Rokeby, Maurice Benayoun, and Jeffrey Shaw.

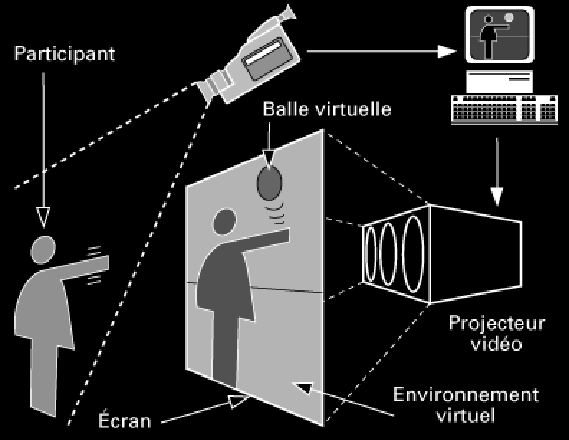

Krueger’s ‘VIDEOPLACE’ (1974) was an early exploration and formation of a responsive environment that responded to movement and gestures. Through a system of video cameras and projectors, the project enabled participants in separate rooms to interact with one another’s silhouettes in real-time.

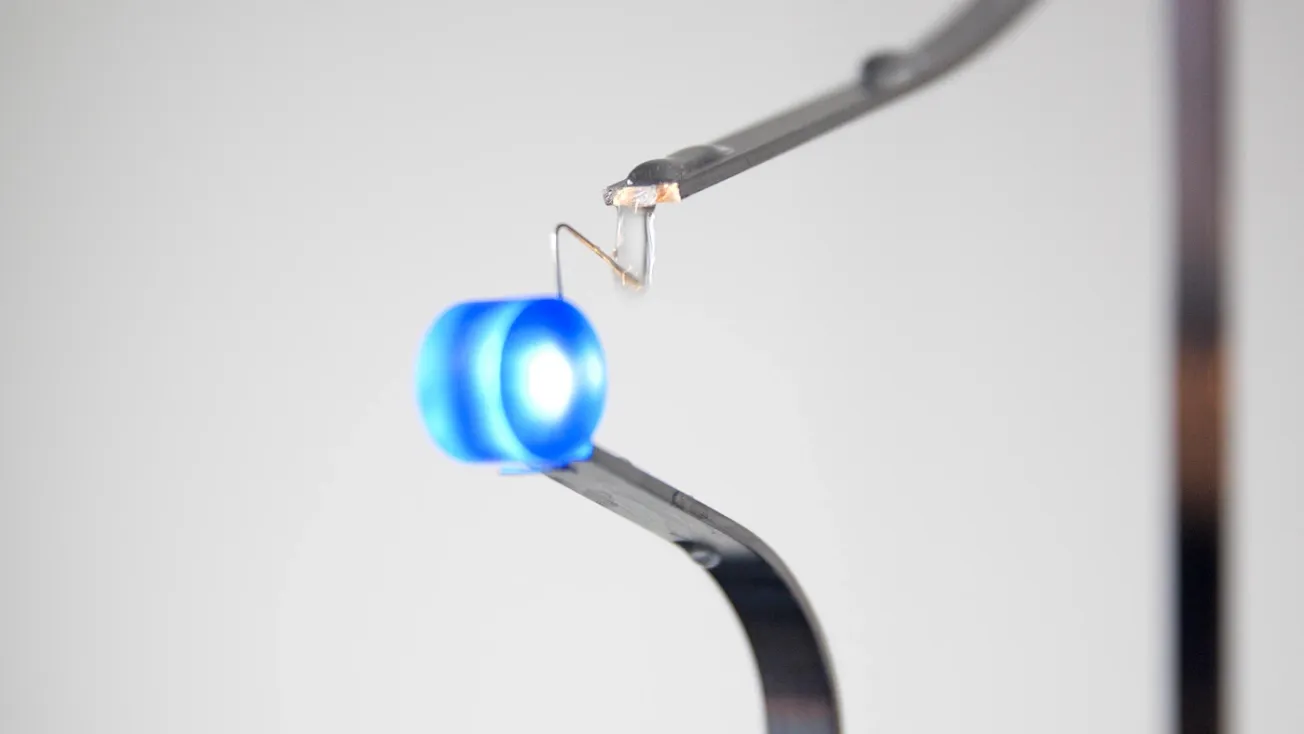

Ascott’s ‘La Plissure du Texte’ (1983), exhibited at the Musee d’Art Moderne in Paris, used computer networking to support the collaborative creation of a ‘planetary fairytale.’ Ascott did not suggest a storyline or plot; participants were invited to improvise. Due to the structure and framework of the piece including time zone differences and participate improvisation, the narratives that emerged were fragmented and overlapping resulting in a sort of “exquisite corpse.” Rokeby’s work, evident in his piece ‘Very Nervous System’ (1993), explored the formation or translation of the bodies movement into sound.

“The active ingredient of the work is its interface. The interface is unusual because it is invisible and very diffuse, occupying a large volume of space, whereas most interfaces are focused and definite. Though diffuse, the interface is vital and strongly textured through time and space. The interface becomes a zone of experience, of multi-dimensional encounter. The language of encounter is initially unclear but evolves as one explores and experiences.” – DAVID ROKEBY

Benayoun’s ‘Tunnel under the Atlantic’ (1995) was a tele-virtual project linking the Pompidou Center in Paris and the Museum of Contemporary Art in Montreal, which was conceivably the first intercontinental virtual reality. Benayoun referred to this as an ‘architecture of communication.’

In Shaw’s ‘Legible City, ’ participants were seated on a stationary bicycle and ‘moved’ through streets projected onto the surface in front of them. The streets here are literally legible, lined not by buildings but by letters. On their passage through the city, visitors could pursue various narrative threads, accumulating their own history of the city – an early iteration of the user’s physical engagement in a virtual environment in the construction of narrative.

These works would foreground the initial generations of artists and designers operating in this domain (which has had no shortage of classifications over the years ranging from new media art, interactive media, and digital art to computational design, emergent technology, etc, etc), including Eduardo Kac, Rafael Lozano-Hemmer, Mark Napier, Jeffrey Shaw, Rirkrit Tiravanija, Golan Levin, Zach Lieberman, Camille Utterback, Scott Snibbe, Thierry Fournier, Salvatore Iaconesi, and rANDOM International – to name just a very small few. Computational technology, Fluxus, and cybernetics have driven the emergence of phenomenology of interaction within a fluid ‘relationship’ between humans and machines. Initiating the current configuration of new fields, domains, and explorations into the bounds of human and computational interfaces in the built environment, networked communications, and information systems – infused in the lived human experience.

How, then, do we contextually position the disciplinary descendants of this love story between the emergence of computation technologies, post-structuralism, and the creative domains?