Voice technology has become part of everyday infrastructure—embedded in phones, cars, and smart homes. Yet few artists examine how these systems decide what counts as a voice. In Up and Away, commissioned by Hyundai Artlab, Christine Sun Kim turns the mechanics of a voice-controlled web game into a study of power, access, and listening itself. What looks like simple play becomes a quiet critique of how technology encodes difference—who it listens to, and who it leaves out.

Reprogramming the Mechanics of Speech

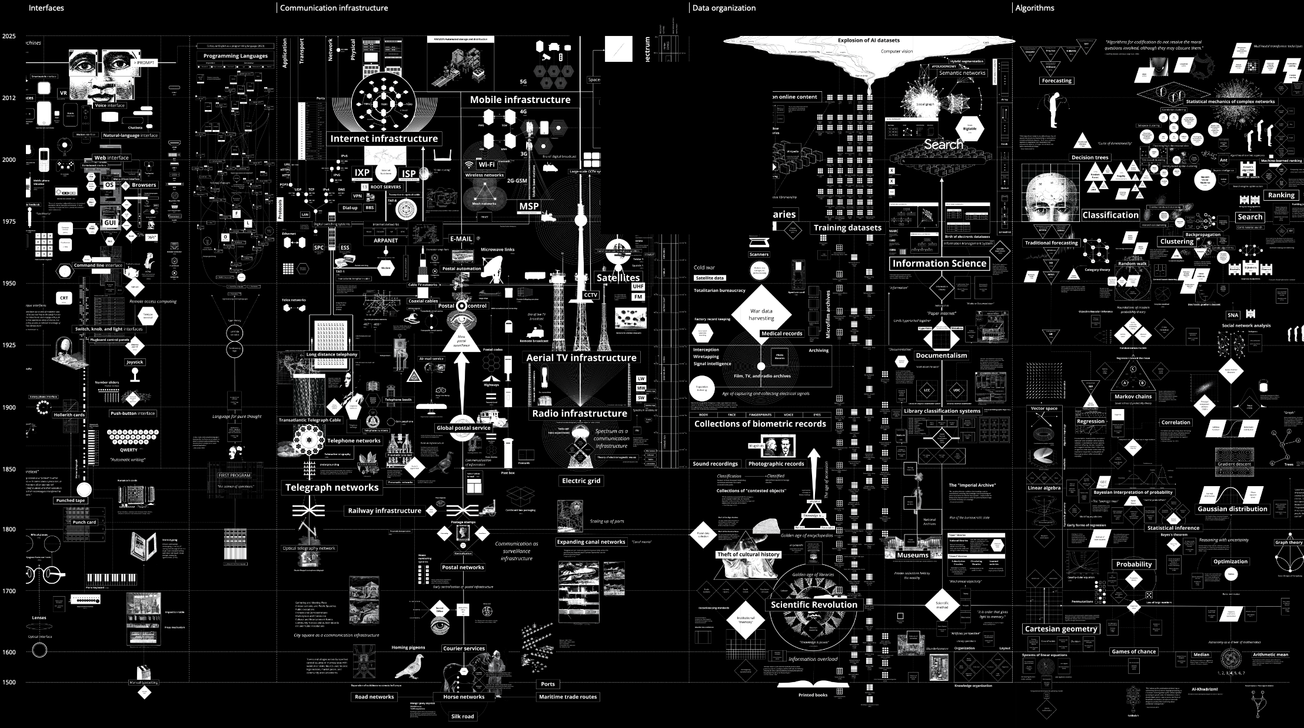

At its surface, Up and Away resembles a standard browser-based voice game: players use sound to move through a sparse digital landscape of icons and floating forms. But Kim’s version resists the logic of entertainment. Instead, it redirects the familiar format of vocal command toward a deeper cultural question—how technologies define “normal” speech and decide whose voices register.

Hyundai Artlab frames the project as a work that challenges conventions of how speech should sound and whose words are given authority. Each icon within the interface reveals a fragment from Kim’s world, referencing personal and cultural narratives that shape her relationship to sound. Through these small interactions, the microphone becomes more than a control device—it’s a site of critical inquiry.

Kim, who has been deaf since birth, has long examined how sound structures social power. Her drawings, performances, and caption-based installations explore the ways hearing and speech confer authority, belonging, or exclusion. In Up and Away, that investigation moves into digital space, questioning the systems that translate—or fail to translate—human expression into data. Rather than relying on spectacle or technical complexity, the work operates with deliberate simplicity. Its icons and visual cues function like musical notation, inviting players to think of sound as relational—mediated by culture, technology, and access. The piece aligns with Kim’s broader effort to reimagine listening itself, positioning the act of speaking—or choosing silence—as a form of authorship. Ultimately, Up and Away reframes voice technology as more than an interface. It becomes a mirror for how societies value certain kinds of sound while rendering others invisible.

The Politics of Listening

The deeper you move into the work, the clearer it becomes that Up and Away is less about gameplay than awareness. It uses the logic of a voice-controlled system to expose how listening is structured—by code, by culture, and by expectation. Kim has described her practice as mapping the “social currency of sound,” and here that investigation becomes interactive. Each icon and waveform within Up and Away reflects fragments from Kim’s world—references to the social and technological systems that define what counts as a voice. The game’s minimal interface becomes both score and map, translating lived experience into a symbolic language of sound and silence.

Voice recognition technology has become embedded in daily life, yet it still struggles to accommodate the full range of human expression. Accents, tonalities, and speech patterns are often misread or erased. For Deaf and hard-of-hearing users, these tools frequently exclude by design. Up and Away doesn’t attempt to correct those flaws—it surfaces them, asking what it means to be audible in a system that decides who can be heard. Visually, the work mirrors Kim’s broader aesthetic: minimalist, graphic, and rhythmically precise. The interface disarms through simplicity, yet every line and icon functions like a caption awaiting meaning. As in her drawings and performances, Kim treats the act of reading sound as a political gesture.

A New Grammar of Voice

Up and Away extends Kim’s long-standing critique of how societies define intelligibility—who is heard, who is translated, and who remains unreadable within dominant systems of communication. Her earlier works, including Degrees of Deaf Rage (2022) and The Star-Spangled Banner (Third Verse) (2020), used notation, performance, and humor to show how institutions choreograph the act of listening. The recent Hyundai Artlab commission brings that inquiry into the space of digital interaction, where voice recognition has become both interface and identity.

The work gestures toward an alternative design logic—one that treats difference not as a flaw to be corrected but as a condition to be understood. By situating the microphone as both medium and metaphor, Kim invites audiences to imagine technologies that might one day listen otherwise: systems that register silence, accent, or ambiguity not as errors but as meaningful input.

In doing so, Up and Away continues Kim’s project of making the architectures of sound and power visible. It doesn’t claim to fix the inequities of voice technology, but it renders them perceptible—reminding us that every act of listening carries a politics of recognition.