Ai Weiwei's return to the UK with his latest exhibition, "Making Sense," at the Design Museum marks a significant artistic and conceptual departure from his previous politically charged installations. This exhibition invites visitors into a sprawling, single-room space at the museum, challenging perceptions of design, materials, and the interplay between authenticity and appropriation.

In contrast to his previous exhibitions characterized by overt political themes, "Making Sense" provides a seemingly neutral platform for Ai Weiwei to explore the fundamental elements of his practice. The exhibition divides the expansive main hall into five distinct 'fields,' each containing an eclectic array of objects that span centuries and cultures. This thought-provoking collection prompts viewers to ponder the tensions between authenticity and imitation, form and function, and the act of making itself.

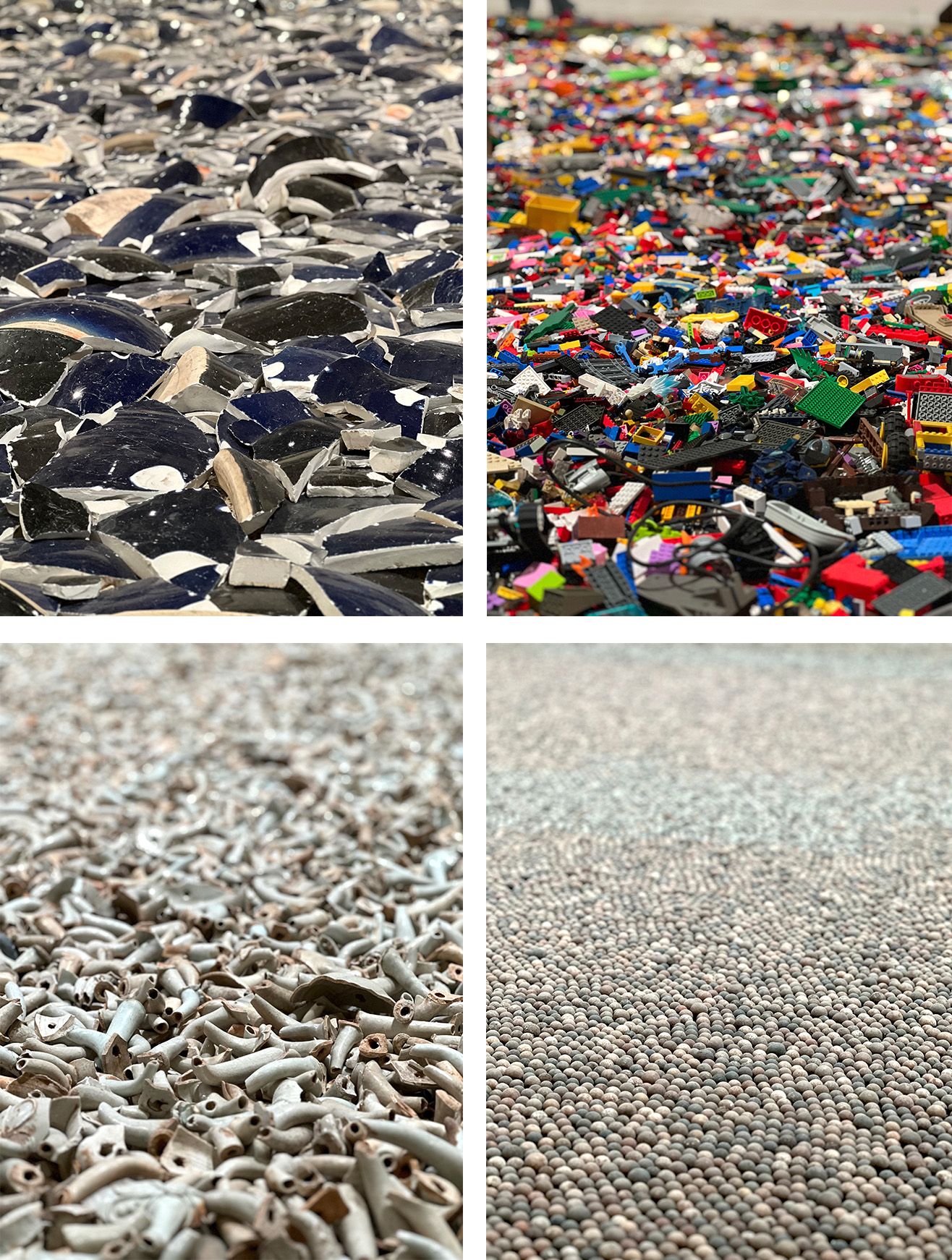

One field within the exhibition appears as if it were an archaeological excavation, displaying thousands of arrowheads and tools dating back to the Stone Age. In juxtaposition, a colorful explosion of plastic Lego bricks fills another field, donated by the public after the Lego corporation refused to supply Ai Weiwei for political works, highlighting the intersections of commerce and artistry. Moving further through the exhibition, visitors encounter an array of weaponry, ancient ceramics, and bonelike teapot spouts, all prompting reflection on the nuanced dynamics of creative expression and suppression throughout history. In his book "Ten Thousand Things: Module and Mass Production in Chinese Art," art historian Lothar Ledderose illuminates the role of modular systems in Chinese art and design, dating back millennia. This tradition allowed for the mass production of standardized components that could be reassembled into many forms and functions, reflecting China's artistic innovation and its underlying political and social control structures.

The exhibition's contextual wall displays provide further insight, featuring photographic series that document the urban transformations in Ai's native city, Beijing. His "Beijing Photographs (1993–2003)" captures the rapid changes as he and his brother frequented flea markets, acquiring antiquities that find a place in the current exhibit. The series "Provisional Landscapes (2002–08)" presents the remnants of traditional dwellings and silenced communities erased by China's modernization. "National Stadium (2005–07)" chronicles Ai's involvement in the design of the iconic Beijing Olympic Stadium, revealing it in various stages of construction. Among the multitude of objects on display, Ai Weiwei emerges not only as an artist but also as a collector, bricoleur, and hoarder of cultural remnants. Every fragment has the potential for repurposing and reframing, challenging the established distribution of the sensible described by Jacques Rancière, and inviting viewers to contemplate the power structures and hierarchies inherent in any community.

Outside the Design Museum, Ai Weiwei's playful yet thought-provoking installations extend the exhibition's themes. Cold, hard marble armchairs that mimic softness and a marble toilet paper roll reflect the unexpected intersections of materiality and comfort. These objects serve as appetizers for the immersive experience that awaits within the museum.

At the heart of the exhibition, five fields of objects laid out on the floor reveal a "geological layer of a lost history." Spanning thousands of years, these objects tell poignant stories. Ai's journey from collecting ancient artifacts to working with mass-manufactured components raises profound questions about craftsmanship, quality, and the essence of creation itself. Ai's use of materials, such as the juxtaposition of surveillance cameras and Twitter logos in the lobby's colorful pattern, highlights the deeper currents of surveillance and control beneath surface aesthetics. The "Coloured House" installation pays homage to a centuries-old house saved from demolition, celebrating the historical amidst the rush toward modernization.

Throughout "Making Sense," Ai Weiwei's subversive commentary weaves through the exhibition. His "Study of Perspective" print series defiantly challenges iconic symbols of Western culture, including the Mona Lisa and the Houses of Parliament. Objects like a Han dynasty urn adorned with the Coca-Cola logo and an iPhone fashioned from a jade hand axe provoke reflection on the commodification of heritage and shifting values. Amidst these provocative elements, Ai's artwork constructed from tiny Lego pieces adds a personal dimension, referencing his father's exile in the 1960s. This juxtaposition against a towering timber installation underscores the exhibition's exploration of craftsmanship. Additionally, films and photos capture the relentless pace of change in Beijing, revealing void spaces between demolition and redevelopment. The Bird's Nest stadium is depicted more as a construction process than a finished result, reflecting Ai's evolving relationship with the project. A large snake crafted from school backpacks commemorates the 2008 Sichuan earthquake, while rebar recreated in marble serves as a memorial to the collapsed schools.

In "Making Sense," Ai Weiwei masterfully blurs the lines between art and design, challenging conventional perspectives and inviting viewers to question the evolving values of craftsmanship, authenticity, and materiality. The exhibition is a testament to Ai's ability to provoke thought and discussion while celebrating the enduring power of creative expression in the face of suppression.