You’re not the author anymore. The polymers are. The mycelium. The carbon fiber, plotting in its lattice.

A growing faction of designers, artists, and architects — backed by the high-voltage philosophies of speculative realism and object-oriented ontology (OOO) — argue that materials aren’t passive mediums. They’re co-conspirators. They push back. They evolve. Sometimes, they even outsmart their makers. The old model of digital fabrication was simple: humans design, machines obey, materials submit. But in this new world, creation looks more like a negotiation — a murky dance where software, substance, and human intention blur into something none of them could produce alone.

“All things equally exist, yet they do not exist equally,” writes philosopher Ian Bogost in Alien Phenomenology, a founding text of this domain. It's a reminder that in the messy ecosystem of creation, human desires aren’t the only gravity wells pulling on form, structure, or meaning. In studios and labs around the globe, designers are starting to listen.

Artists and Designers Listening to Materials

Few embody this shift more vividly than Anicka Yi, whose installations dissolve the boundary between organism and artifact. Yi’s use of organic compounds, bacterial cultures, and synthetic materials questions the hierarchy between the animate and inanimate. In works like In Love with the World, the materials evolve autonomously over the course of the exhibition, suggesting a kind of material memory and aspiration.

Thomas Feuerstein likewise crafts biochemical sculptures that literally live and die. His work challenges the notion of static form, positioning materials as mutable, self-organizing systems. By feeding microorganisms or growing metabolic sculptures, Feuerstein foregrounds the agency of matter itself.

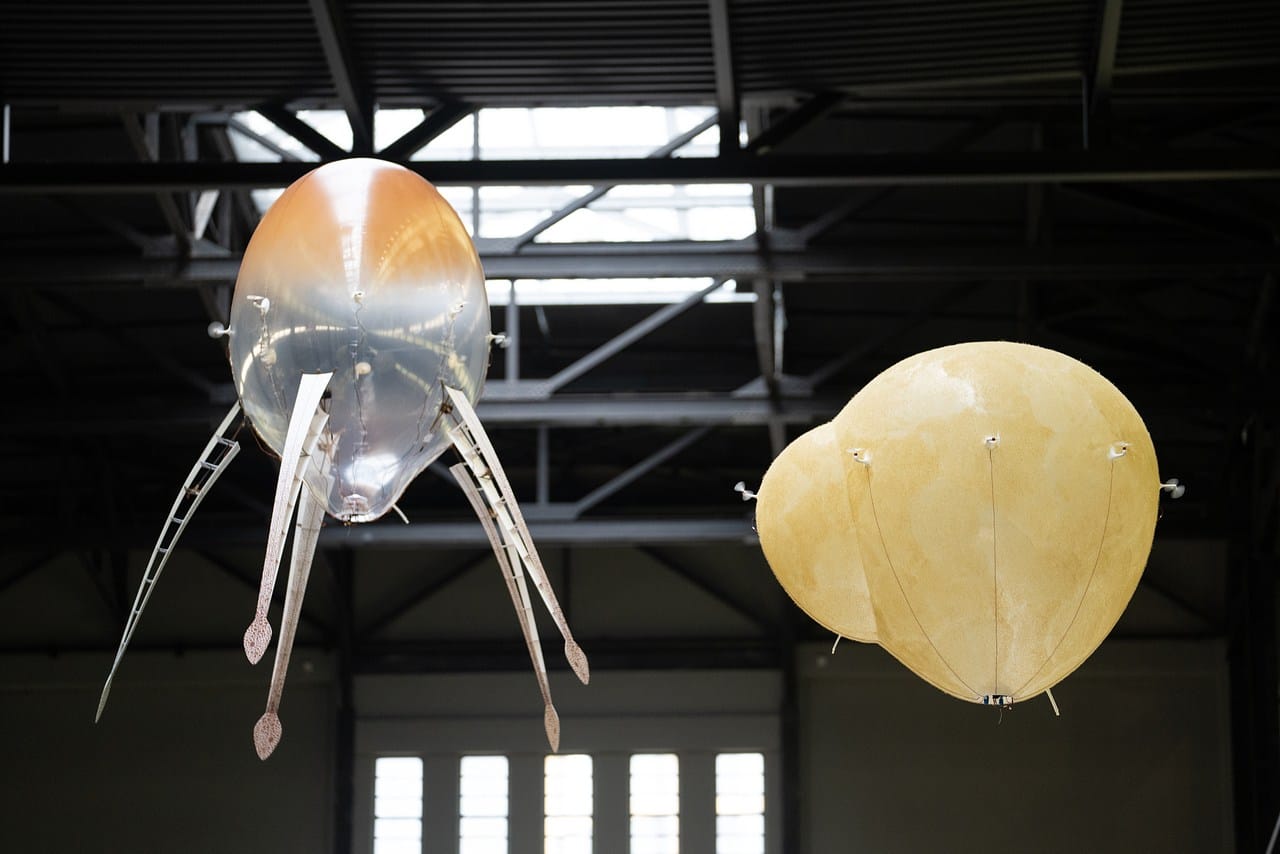

Studio Drift, led by Lonneke Gordijn and Ralph Nauta, creates kinetic sculptures that mimic natural behaviors such as flocking or blooming. Well-known pieces such as Shylight respond to viewers and environmental cues, effectively granting silk, aluminum, and electronics a kind of behavior or instinct beyond human scripting.

In architecture, Jesse Reiser and Nanako Umemoto (RUR Architecture) treat matter as an active force shaping the built environment. Their projects integrate digital modeling and material feedback loops, blurring authorship between software, designer, and material response.

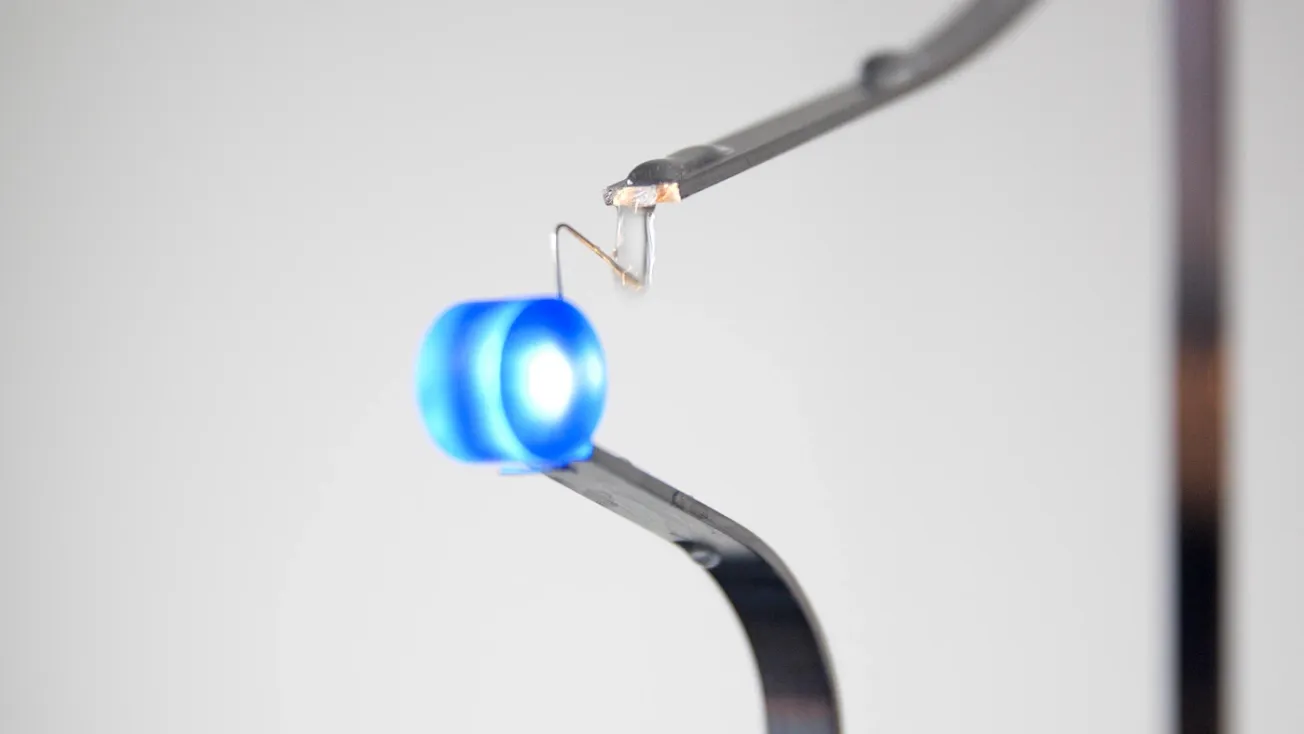

Kelly Heaton, operating at the junction of art and electrical engineering, constructs analog circuits that mimic biological life. Her self-sustaining electronic systems pulse, breathe, and behave, proposing a vision of matter as sensate and expressive.

Rachel Armstrong pushes even further, exploring protocell technologies — synthetic chemical systems capable of growth and adaptation. In her view, architecture itself could one day grow from these living materials, rendering the architect less a designer than a facilitator of material will.

"The practice of experimental architecture through living architecture is embracing a paradigm that is emerging…that paradigm shift is the transition from an industrial era of thought and design towards an emerging and undefined ecological era." - Dr. Rachel Armstrong

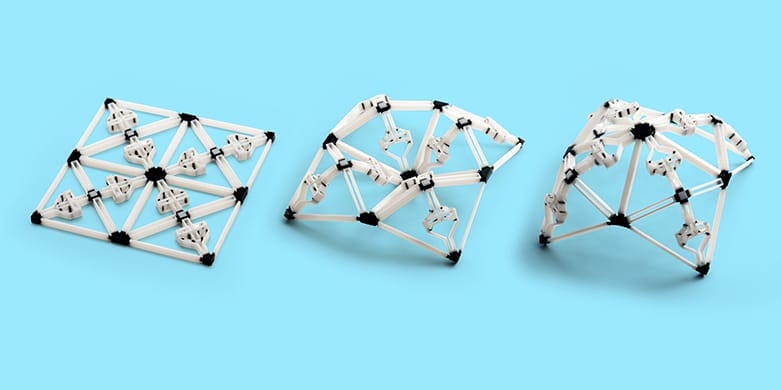

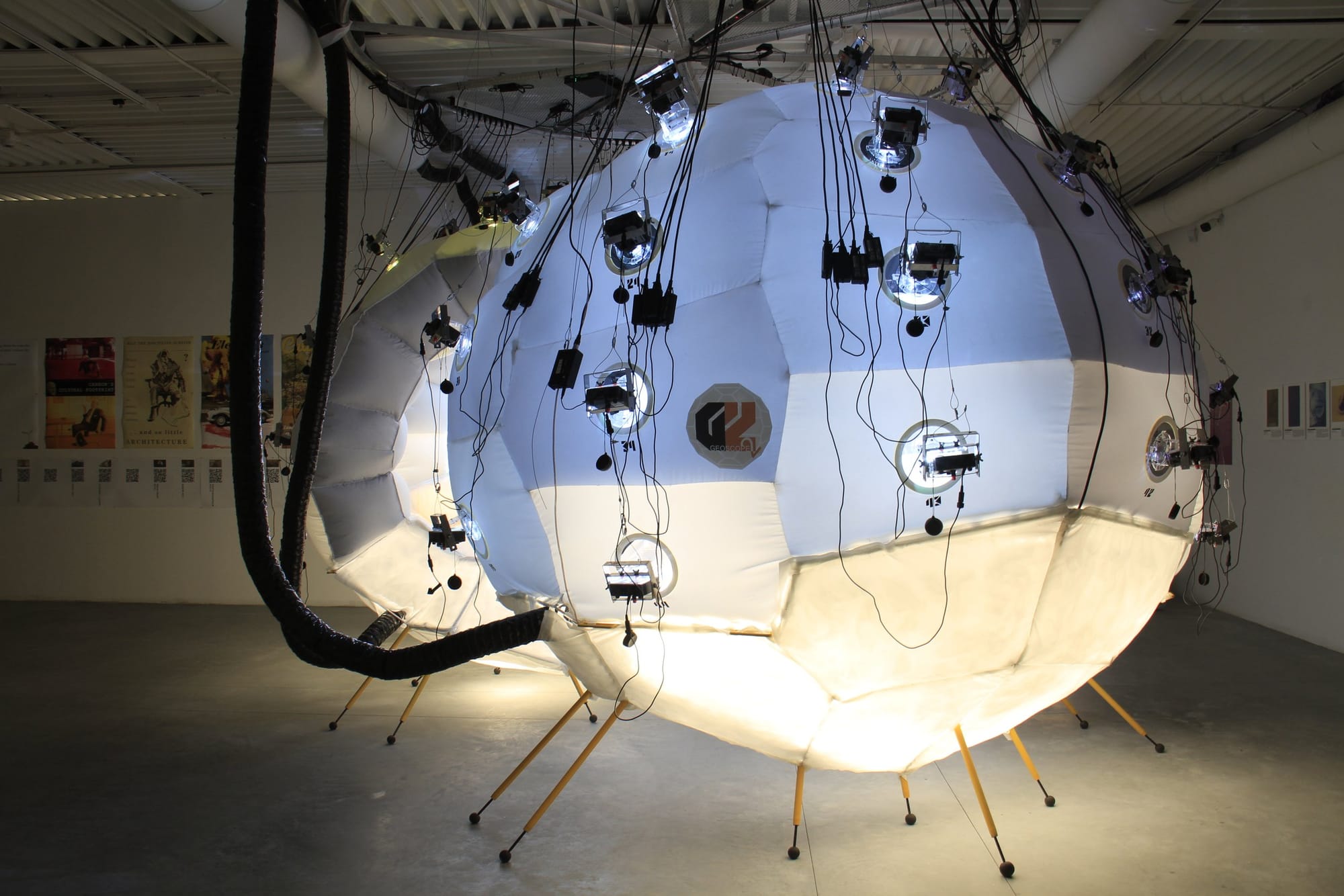

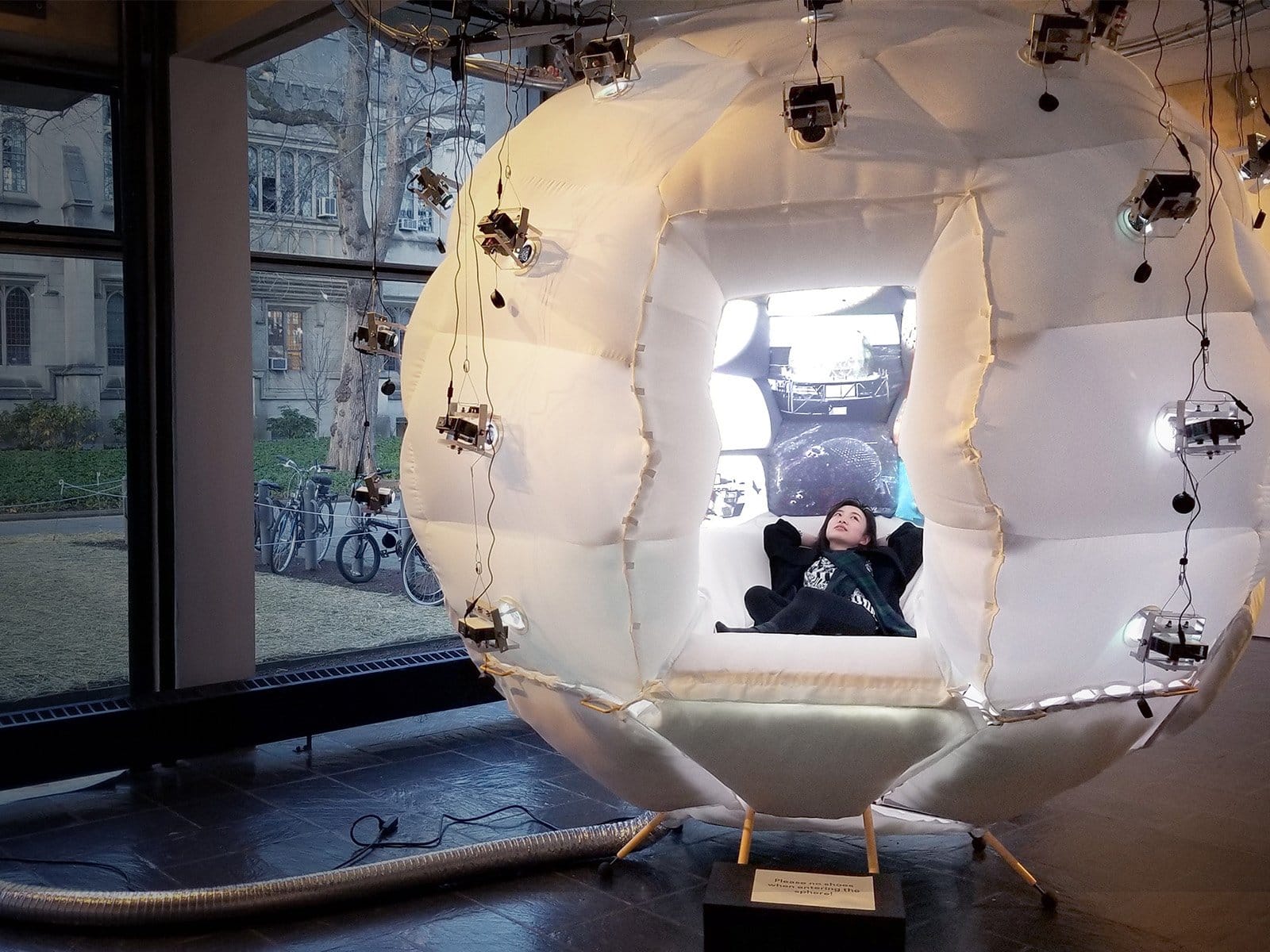

The work of Philip Beesley inhabits this vision already. His living architecture sculptures, composed of tens of thousands of lightweight, responsive components, blur the line between environment and organism. Beesley’s installations don't just respond to human presence; they behave as semi-autonomous ecosystems.

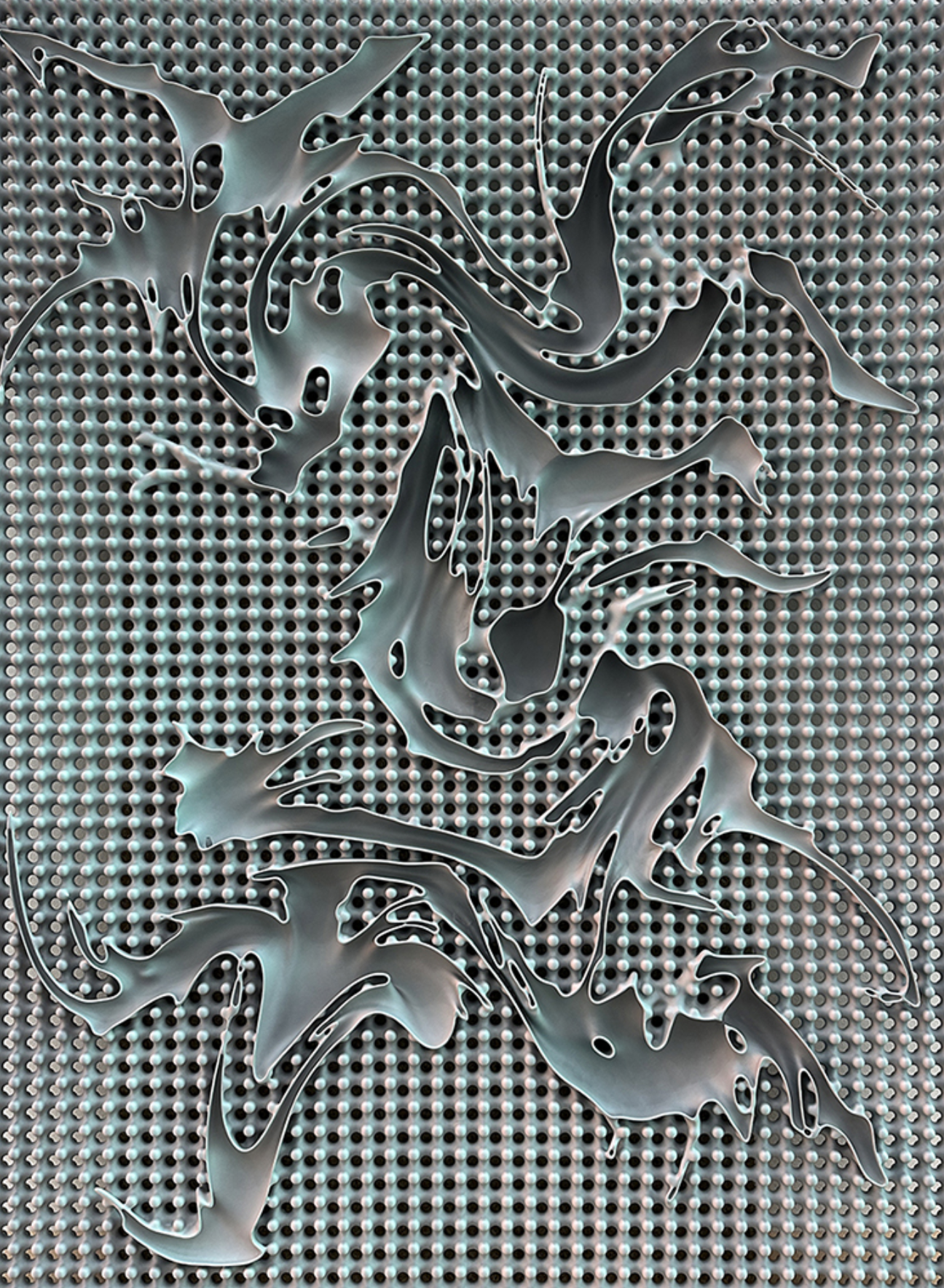

Daniel Widrig approaches this dynamic from a generative design perspective. His digitally fabricated structures emerge from algorithmic simulations where material behavior — stress, strain, growth — directs form, diminishing the designer’s hand. Even in the corporate frontier, material agency is being explored.

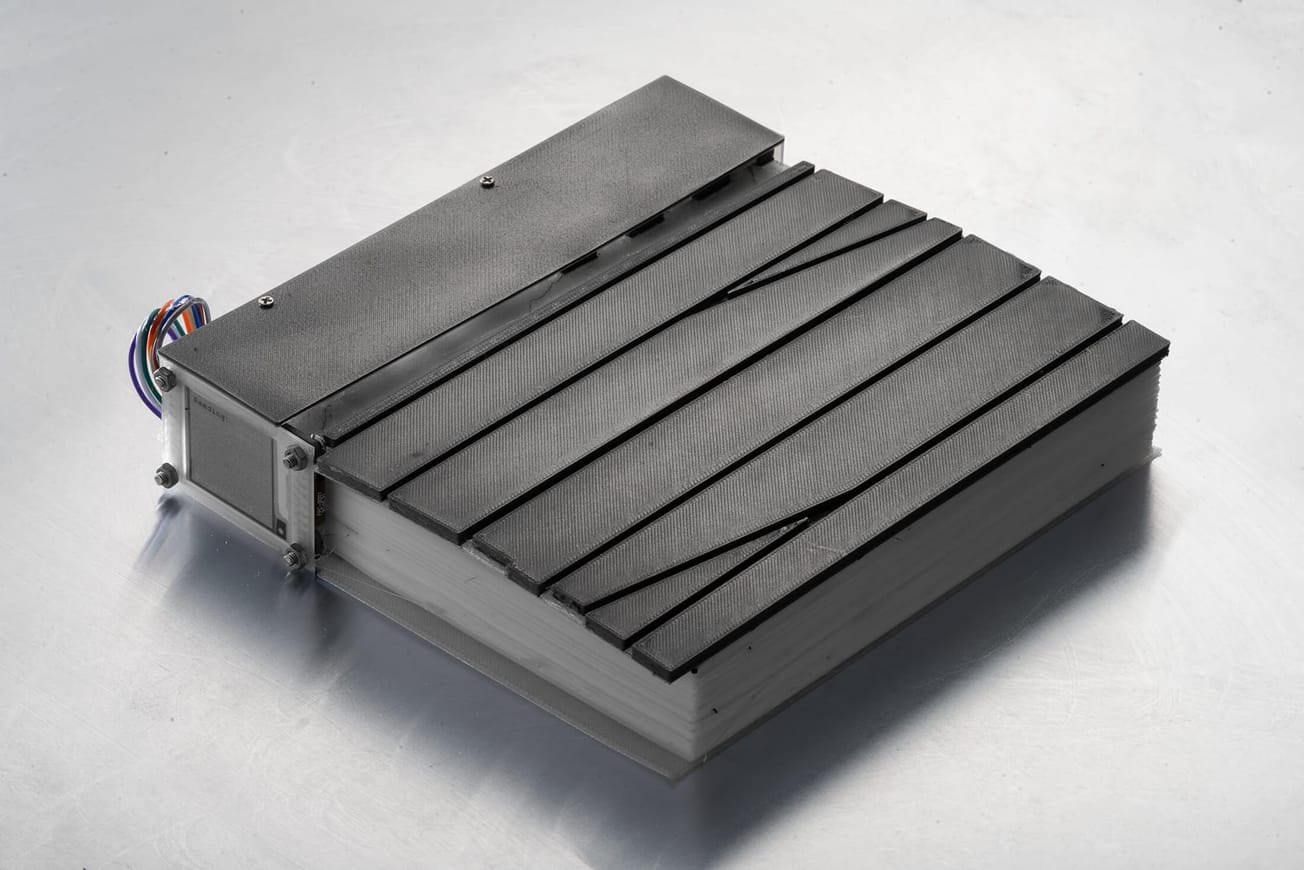

Ivy Ross and Google’s Advanced Technology and Projects (ATAP) group, particularly through Project Jacquard, weave interactivity into the fibers of textiles themselves, allowing fabrics to become responsive, communicative entities.

And threading through all of this is the philosophical scaffolding of Ian Bogost. His call to "look at objects sideways" invites a design practice that neither romanticizes nor instrumentalizes materials, but rather engages them as beings with their own logics and desires.

Toward a Non-Human Aesthetic

If materials can dream, then designers must learn to listen. The future of digital fabrication may hinge not on better command of matter, but on deeper attunement to its intrinsic capacities. Generative design tools, bio-fabrication technologies, and AI-assisted modeling are not merely extending human abilities — they are creating spaces where human and non-human agencies entwine, producing outcomes neither could achieve alone. This new paradigm doesn't negate human creativity. Instead, it situates it within a broader ecology of creation, where stone, polymer, fungus, and fiber are co-authors. As speculative realism and OOO suggest, the world is not built for us, but with us — and increasingly, by the materials themselves.

"To be a thing is to have a world," Bogost reminds us. In the unfolding future of design and fabrication, it seems clear: materials have worlds of their own, and we are merely guests.