While screens still dominate interface design, haptic-first systems are steadily expanding their role. From research labs to artist studios, new projects are exploring how touch, movement, and spatial interaction can complement—or in some cases replace—visual displays. These systems go beyond presenting information on a flat surface, enabling users to feel, manipulate, and physically engage with digital content, reframing the relationship between the body, space, and computation.

Restoring Physicality to Digital Interaction in Haptic-First Interfaces

The Tangible Media Group at MIT Media Lab, led by Hiroshi Ishii, is arguably one of the leaders in tangible and haptic-first interaction design. Ishii’s work reframes interaction design around the concept of tangible bits—digital information that takes a physical form. Projects like inFORM, a dynamic pin display, render shape and motion in real time, allowing users to reach into a digital model and manipulate it physically.

Materiable, another Tangible Media Group project, simulates the behavior of materials such as water, rubber, or sand using an array of actuated pins—modulating movement and resistance to suggest different physical properties. Both systems explore how touch and form can carry as much information as pixels on a screen.

Together, they illustrate a shift in interaction logic: instead of flattening experiences into visual representations, they give computation spatial and tactile presence. For designers, this opens possibilities in fields from data visualization to telepresence—where touch can transmit meaning as effectively as sight or sound.

Touch Without Contact: Mid-Air Haptic-First Interaction

While Ishii’s work focuses on physical actuators, Ultraleap—formerly Ultrahaptics—has pioneered mid-air haptic feedback. Using arrays of ultrasonic transducers, the system generates focal points of pressure in the air, creating tactile sensations that can be felt without any physical contact. The technology has been deployed in automotive controls, VR/AR environments, and public installations where hygiene or accessibility concerns make physical touch impractical. Mid-air haptics address a core interaction challenge: how to deliver tactile feedback in contexts where a physical interface isn’t feasible. They also expand the design space for gestural interfaces, pairing the intuitiveness of touch with the flexibility of spatial computing.

Toolkits for Designing Haptic-First Interfaces

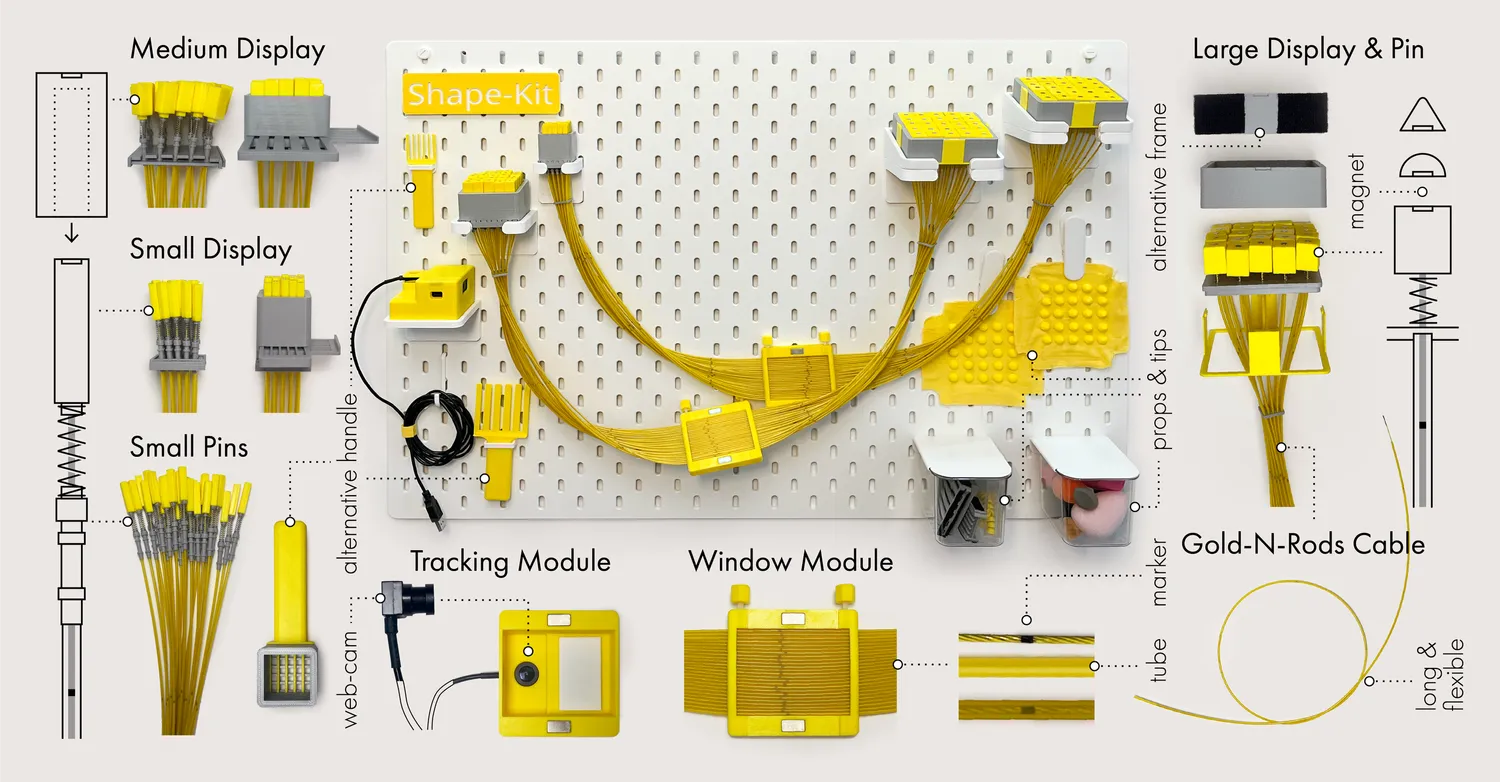

As haptic-first interaction matures, designers need tools to prototype and refine tactile experiences. Several recent toolkits bridge the gap between research and practice. Shape-Kit supports on-body expressive haptics through actuated tactile elements, enabling collaborative prototyping of wearable touch experiences. hDesigner offers a real-time pattern editor that lets designers feel and iterate tactile patterns instantly—accelerating workflows for applications in music, film, and performance.

Other experimental platforms expand beyond wearables. HapKnob, a motorized shape-changing knob, adapts its physical form to match different control states, offering clear tactile cues without requiring visual attention. AdapTics provides a toolkit for designing and testing adaptive mid-air “tactons”—tactile icons that adjust in real time to user movement, critical for XR environments and responsive installations. These tools signal a shift toward making haptic interaction a first-class design medium, on par with typography, color, and motion.

Designers Expanding Haptic-First Interface Design

Beyond the lab, individual designers are pushing haptic-first principles into unexpected contexts. James Patten, an alumnus of MIT’s Tangible Media Group and founder of Patten Studio, develops kinetic and tangible computing installations that integrate computation directly into physical environments. Notably, among his works, Lift is a motorless, heat-responsive light feature that unfolds organic, flower-like movement in response to human presence. Using shape-memory alloy ("muscle wire") and low-resolution thermal sensing to animate petals toward people, this installation exemplifies how touch and presence can become the primary channels for interaction.

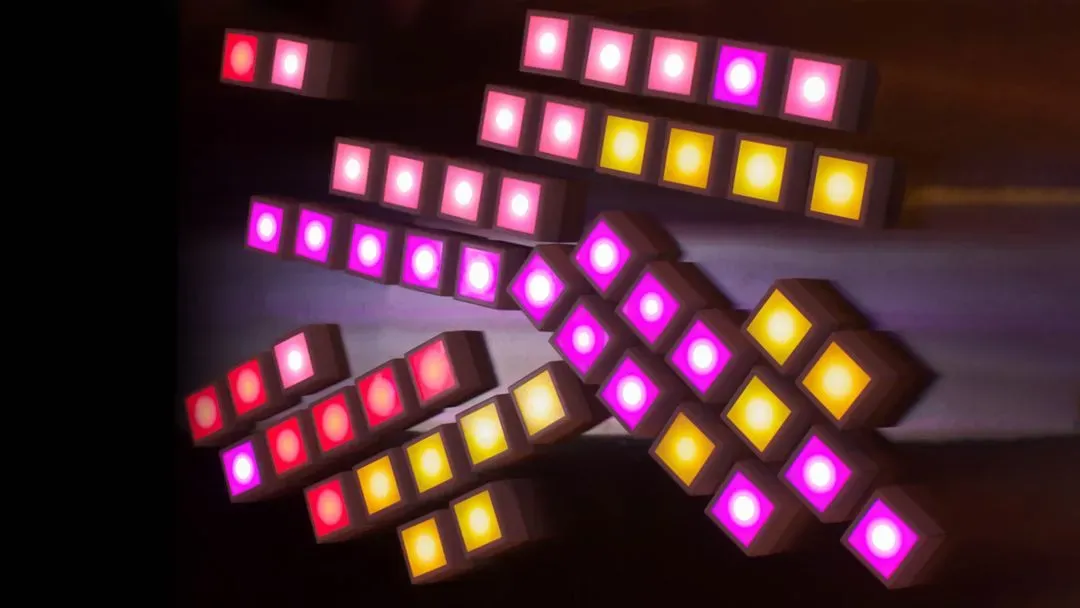

Dhairya Dand, founder of ODD Industries, brings haptic feedback into everyday mobility with inventions like SuperShoes, insoles that use gentle directional cues to guide wearers through a city. The project shows how haptic-first systems can deliver navigational or contextual information discreetly, without demanding visual attention. Marcelo Coelho, of MIT’s Design Intelligence Lab, creates responsive materials and surfaces where haptics are integral to interaction. His projects extend tactile design into wearables, furniture, and spatial installations, turning the material itself into the interface. One example is Six-Forty by Four-Eighty, a large-scale interactive lighting installation composed of approximately 220 magnetic pixel-tiles that respond to touch and use the visitor’s body as a conduit for communication—enabling patterns and animations that physically express computation.

Ephemeral, Tactile, and Environmental Approaches

Some studios approach haptics from a cultural and experiential perspective. Studio Swine has produced “ephemeral tech” installations that dissolve the interface into the environment. Their New Spring installation for COS at Salone del Mobile used a custom mechanism to create scented mist-filled bubbles that burst upon contact, engaging visitors through sight, scent, and touch. While not conventionally “haptic” in the device-driven sense, Studio Swine’s work underscores a broader truth: the design of touch is as much about shaping material and spatial experiences as it is about engineering actuators.

Designing Beyond the Screen in Tactile Interface Design

The rise of haptic-first systems challenges long-standing design assumptions. Screen-based UX principles—hierarchies of visual elements, color coding, and typographic clarity—don’t directly translate when the primary medium is vibration, deformation, or force. Instead, designers are working with new variables: amplitude, frequency, perceived texture through vibration patterns, and spatial mapping of touch. This shift has implications far beyond industrial design or gaming. In accessibility, haptic-first interfaces can deliver rich information to users with low or no vision, or reduce cognitive load by moving certain interactions away from the eyes entirely. In automotive design, tactile feedback can improve safety by minimizing glance time. In immersive media, haptics can create embodied experiences that visual effects alone cannot match.

Crucially, designing without screens is not about eliminating visual interfaces but rebalancing them—integrating touch as a primary modality rather than a peripheral afterthought. The most compelling projects in this space treat haptics as a cultural medium, capable of shaping meaning, emotion, and memory.

The Road Ahead for Haptic-First Interaction

For designers working in this emerging field, the challenge is twofold: technical and cultural. Hardware and software constraints still limit the resolution, expressiveness, and portability of haptic systems. At the same time, conventions for “reading” haptic signals are still nascent—there’s no universally understood tactile equivalent of a red stop sign or a hyperlink. Yet the momentum is clear. The combined efforts of research labs like Tangible Media Group and Ultraleap, toolkit developers behind Shape-Kit and hDesigner, and designers ranging from James Patten to Studio Swine point to a design landscape where interaction is grounded in the physical world, not just represented on a screen.

The move toward haptic-first interfaces is less about replacing the screen than about rediscovering the body as a primary site of interaction. As tools become more accessible and tactile interaction literacy grows, designers will have an expanded palette for crafting experiences—one where the language of touch is as carefully considered as the language of sight.