For decades, design has revolved around a singular protagonist: the human. Often imagined as rational, individual, Western, and able-bodied, this figure has shaped everything from interface logic to architectural ergonomics. But what happens when that center no longer holds?

"Designing for the post-human" doesn't mean abandoning the human—it means displacing human exceptionalism as the only reference point. In its place: a tangled mesh of systems, species, algorithms, materials, and scales. This shift isn’t about sci-fi futures. It’s about now—built on a lineage of critical design, systems thinking, and ecological ethics.

Design After Human-Centeredness

Human-centered design promised empathy, usability, and inclusivity. But it also quietly reinforced a hierarchical worldview—one where nature is background, AI is tool, and everything else is a means to human ends. While its rise in the early 2000s marked a critical departure from top-down, corporate design practices, it has since ossified into a framework that too often centers a narrow, market-defined vision of the human: typically Western, able-bodied, neurotypical, and digitally connected.

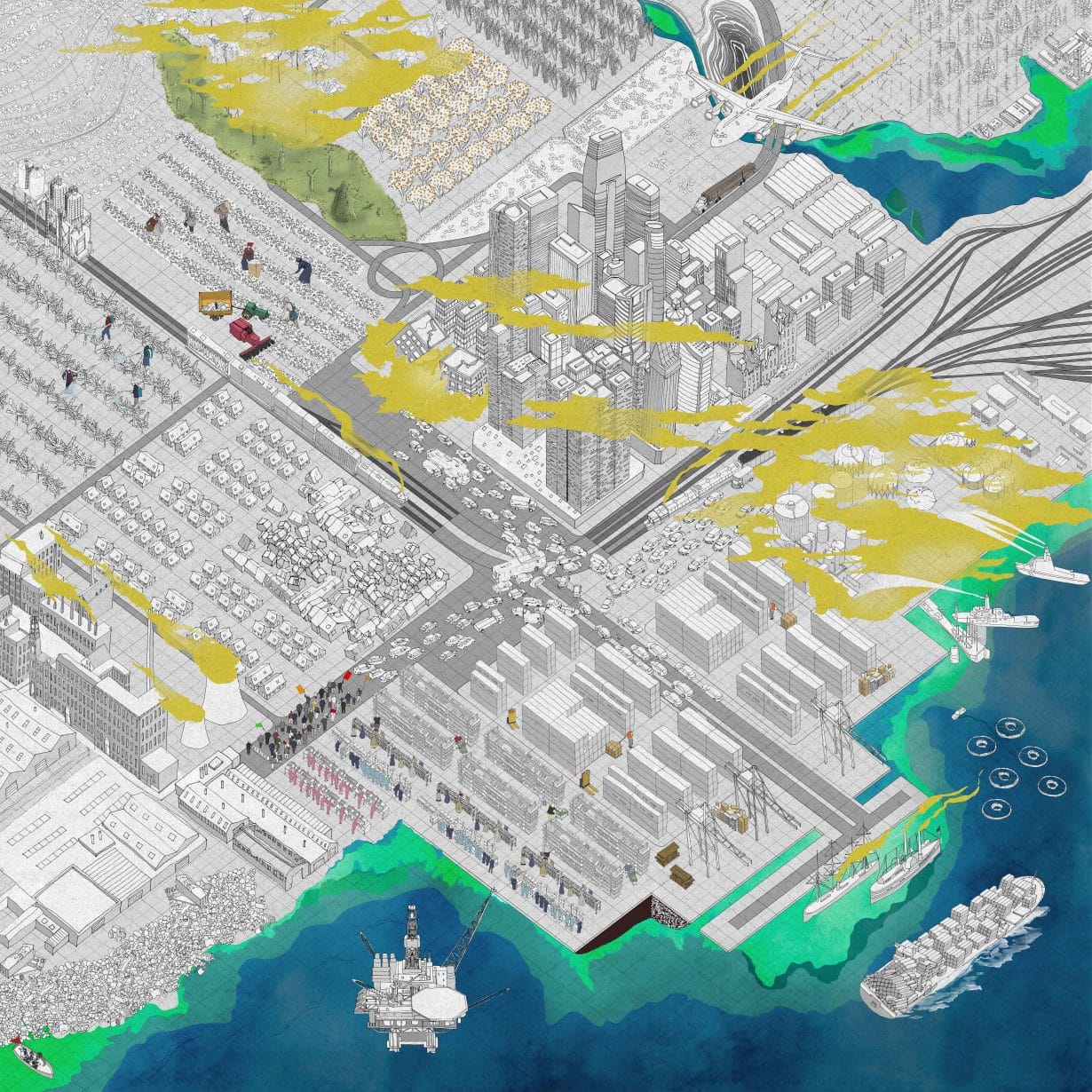

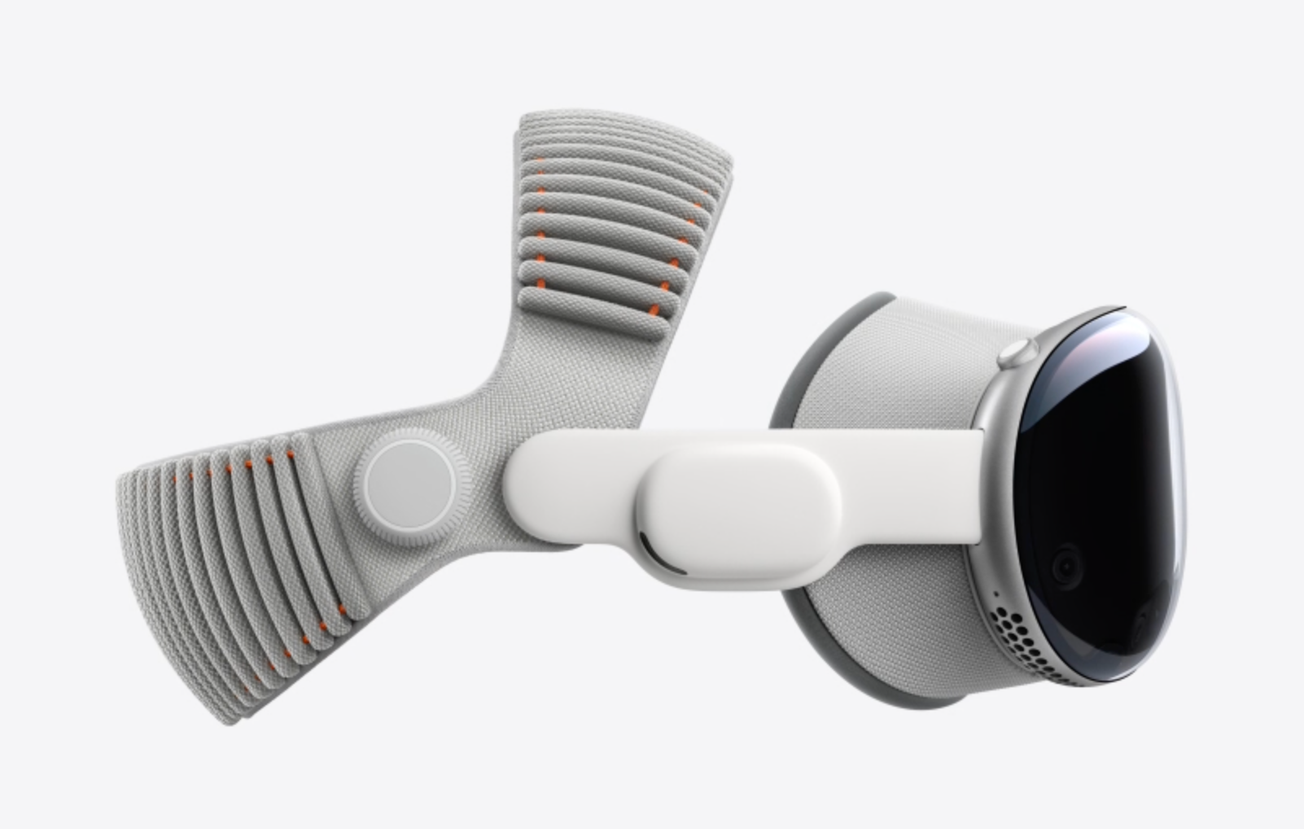

In practice, “human-centered” has become shorthand for user-centered convenience. Think of algorithmic interfaces that optimize for click-through rates, or smart devices that privilege personal comfort over planetary cost. These systems funnel human attention, extract behavioral data, and reinforce anthropocentric control—rarely accounting for the ecologies they exploit. The broader networks—environmental, microbial, machinic—that sustain or are exploited by these designs are rendered invisible. Post-human design interrogates that hierarchy. It asks: What would it mean to design with microbes, for pollinators, through algorithms, and within ecologies that outlast our species?

Projects like Pollinator Pathmaker by Alexandra Daisy Ginsberg make this tangible. Instead of designing gardens for human aesthetics, Ginsberg uses algorithmic modeling to optimize floral diversity based on pollinator preferences—bees, butterflies, hoverflies—positioning them as the primary “users.” The result: living systems that shift the axis of value away from us.

Elsewhere, speculative tools like the More-Than-Human Manifesto by Superflux offer designers practical frameworks for multispecies thinking. It’s not just about acknowledging nonhuman actors—it’s about embedding their presence into planning processes, timelines, and governance models. The goal isn’t empathy, but accountability across species boundaries.

Post-human design doesn’t reject human needs. It reframes them in relation to the systems we co-inhabit and co-impact. The challenge is not to erase the human, but to de-center it—so that design becomes a platform for negotiating interdependence rather than projecting dominance.

Systems with Agency

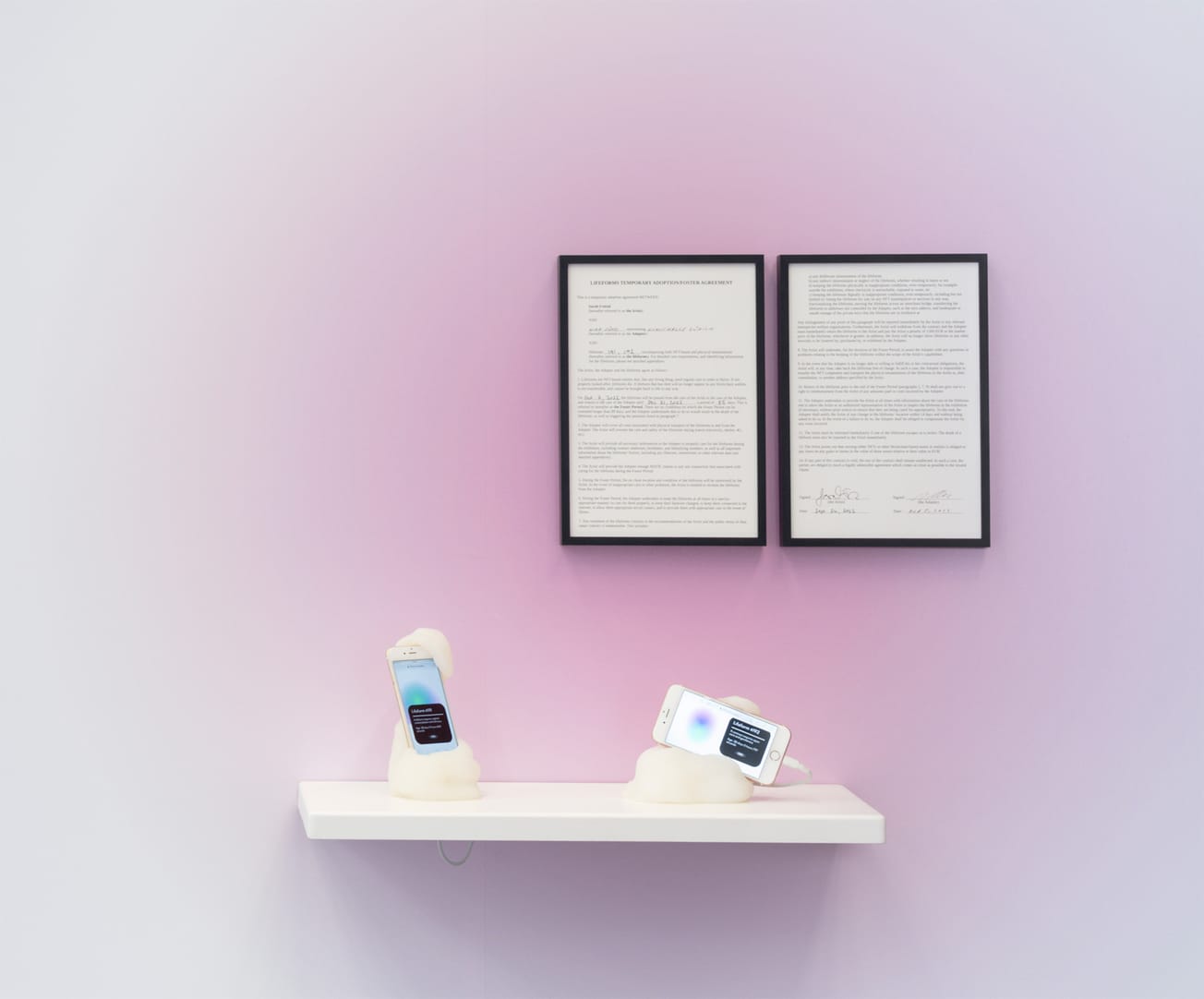

Post-human design embraces distributed agency. It’s less about tools extending human will and more about co-constructing systems where agency is networked, messy, and partially unknowable. Take Haroon Mirza’s Modular Operandi (2019–ongoing), a system of solar-powered sound sculptures that respond to environmental stimuli—light, temperature, electromagnetic fields—and to one another. Installed in both natural and institutional settings, these works operate autonomously, generating unpredictable rhythms and interferences. Mirza’s design relinquishes authorial control in favor of emergence. It’s not about interactivity. It’s about coexistence with a system that has its own logic.

Or consider Heather Dewey-Hagborg’s T3511 (2018), a speculative bio-art narrative based on the extraction and manipulation of a subject’s genetic material. The work interrogates agency at the molecular level: Who owns genetic data? What systems of power emerge when bodies become informatic? Dewey-Hagborg’s piece isn’t “interactive” in the traditional sense—it’s invasive, embodied, and structurally post-human.

These aren’t systems designed for user delight. They’re interventions in complex techno-biological networks where the designer is just one node among many.

Material Becomes Collaborator

Post-human design resists the idea that materials are passive substrates awaiting human form. Drawing from theorists like Jane Bennett (Vibrant Matter) and thinkers in new materialism, designers explore materials as active participants in systems. Case in point: Rachel Armstrong’s research into protocell architectures—non-living chemical systems that exhibit lifelike behaviors like self-assembly or environmental responsiveness. These aren’t speculative metaphors. They’re proposals for living buildings that metabolize carbon, grow, and decay—more garden than monument. It’s a refusal of permanence. A move from finished object to processual system.

The implications aren’t limited to sculpture or architecture. Designing with material agency opens up questions for infrastructure, energy, and climate adaptation. Can we design networks that degrade responsibly, absorb shock, or evolve with changing conditions? It’s not about resilience in the classical sense, but about adaptability within volatile environments—whether urban or planetary. This perspective reframes design from static solution to dynamic steward. Systems thinking becomes a baseline. Iteration becomes survival.

Ethics Without Guarantees

Designing for the post-human also means confronting uncertainty. If agency is shared and futures are indeterminate, then design can’t promise control. Instead, it demands accountability, care, and humility. Maria Puig de la Bellacasa’s concept of “matters of care” reframes design as a practice of ongoing maintenance—not mastery. It's echoed in feminist tech labs, decolonial design studios, and multispecies architecture practices that refuse simple fixes and instead cultivate enduring, messy, ethical relations.

This reframing matters because many of the systems designers now touch—AI models, ecological interventions, genetic engineering, planetary computation—are non-reversible. Once released, their trajectories can’t be rolled back or fully predicted. Design ethics, then, must move beyond harm reduction or consent checklists. It becomes a commitment to staying with complexity, to designing in ways that are responsive over time, across actors, and through unintended consequences.

For example, working with machine learning systems trained on massive datasets raises questions about whose knowledge is encoded, whose histories are erased, and how outputs reinforce or subvert power. In biomaterials or synthetic biology, the question isn’t just functionality—it’s what lives are being modified, monitored, or instrumentalized in the name of innovation. Post-human ethics doesn’t offer closure. It offers orientation: toward situatedness, accountability, and slow design. It asks designers to think across time horizons, across species boundaries, and across uneven systems of harm. The ethical demand is not perfection. It’s persistence.

So What Now?

Post-human design isn’t a style or aesthetic. It’s a shift in orientation—away from usability as a universal good, and toward design as a site of negotiation among diverse, often conflicting forms of agency. It demands that designers confront the limits of anthropocentrism, interrogate inherited notions of neutrality, and rethink what responsibility looks like when humans are just one node in a larger mesh of systems.

This doesn’t mean abandoning human needs. It means situating them within wider ecologies—material, algorithmic, planetary—and designing with an awareness that outcomes ripple far beyond immediate users. The work involves developing practices that are collaborative rather than extractive, that foreground process over product, and that hold space for ambiguity, emergence, and entanglement. Instead of assuming a stable subject and a defined problem, designers must engage with systems that evolve, decay, and resist resolution.

For those working at the intersection of technology, art, and ecology, the central question is no longer how design can serve human goals more efficiently. The question is: how can design responsibly intervene in environments where control is partial, time is nonlinear, and the most affected stakeholders may not be human—or even alive yet?

In this context, post-human design becomes less a speculative thought experiment and more a practical necessity. It’s a framework for designing amid instability, and a method for engaging with futures that are already unfolding.