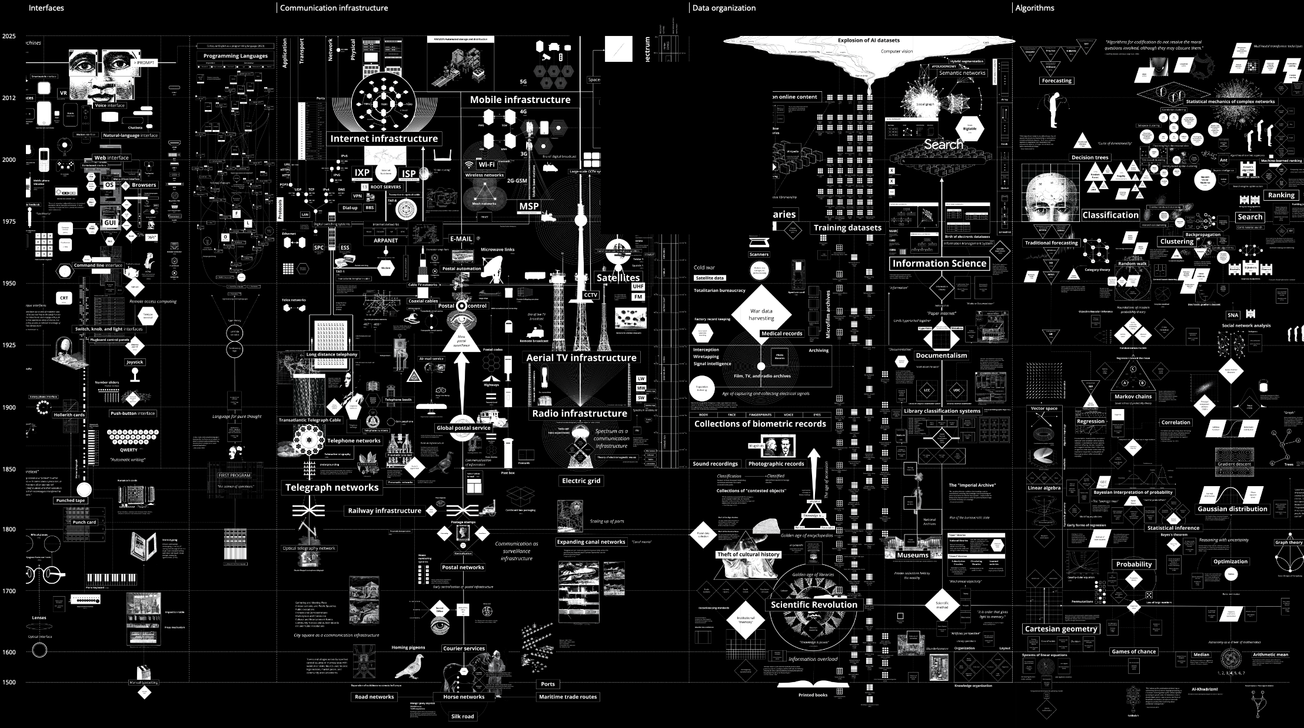

Interfaces now operate as policy. Every toggle, dropdown, and confirmation flow encodes a worldview—sometimes intentionally, often by default. As digital systems scale across finance, civic infrastructure, and everyday communication, interaction design has become an engine of soft governance. Not the legislative kind, but the procedural rules that determine how people coordinate, what actions are possible, and who gets to participate.

This shift isn’t ideological. It’s structural. Distributed networks depend on UI scaffolding to make complexity manageable. Corporate platforms use interface architecture to frame what counts as consent. Civic tools convert municipal processes into clickable workflows that either expand or shrink public agency. Governance is migrating from law to layout. The question is no longer whether design shapes power. It’s how deliberately we’re willing to treat it as a governance layer.

Interfaces as Protocols: The Narrow Bandwidth of Decentralization

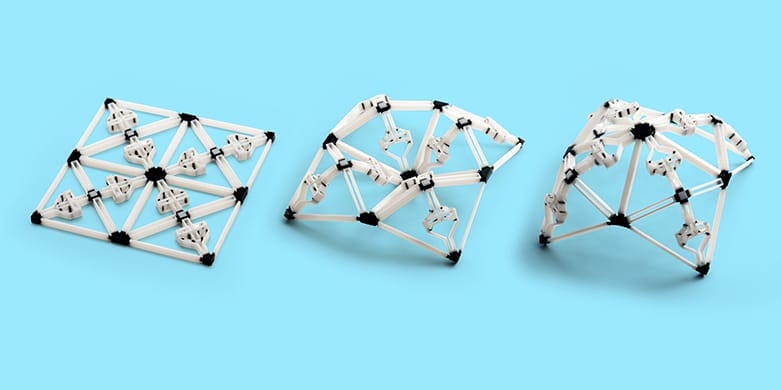

Blockchain systems make this visible. Ethereum’s mechanics are abstract, but wallets, dashboards, and explorers function as translation layers that define how the network is experienced. These aren’t neutral windows—they’re governance surfaces.

Designer and researcher Kei Kreutler describes how DAO interfaces shape the mental models of collective ownership. The metaphors—treasuries rendered as financial dashboards, voting as a slider bar, membership as a colored graph—preset expectations about what participation means. When the UI compresses governance into a single action, it narrows the imagination of what governance could be.

Artist and developer Sarah Friend extends this further by designing systems where participation requires sustained care or social negotiation. Her work makes visible how UI mechanics can enforce norms: a button that expires, a screen that requires collaboration, an interaction that demands accountability. The interface becomes a rulebook, not an illustration.

Decentralization often promises openness, but UI constraints determine what “open” actually looks like. A multisig workflow that’s confusing or rigid reshapes who can coordinate. A wallet recovery path that requires technical fluency alters who feels safe participating. Governance, in practice, becomes whatever the interface allows.

Corporate UX and the Quiet Politics of Permission

At the opposite end of the spectrum sit tightly controlled ecosystems. Here, governance emerges not through collective coordination but through UI-defined boundaries. Apple’s privacy settings are a prime example. When the company pushed tracking permissions into explicit pop-ups, mobile advertising economics shifted almost instantly. A modal window became a policy instrument powerful enough to reroute revenue across entire industries. That’s interface as regulation, executed through design rather than legislation. But Apple’s patterns also show the limits of corporate-defined agency. Whether a user selects “allow once,” “allow while using the app,” or “don’t allow,” the interface frames privacy as a series of choices that fit Apple’s architecture—and Apple’s business priorities. What isn’t presented isn’t considered.

Designer and researcher Caroline Sinders has examined how reporting tools and moderation flows on major platforms codify permissible forms of expression. The labels in a dropdown menu define the boundaries of harm. The number of steps in a submission process influences whether people speak up. These structures aren’t decorative; they’re forms of governance embedded in UX. Corporate UX, then, operates as a policy membrane. It decides how much friction users encounter, which decisions require confirmation, and which are silently automated. Each choice carries political weight.

Civic Interfaces and the Architecture of Participation

Cities are increasingly governed through portals, dashboards, and consultation tools. Civic tech aims to make processes legible, but the interface often becomes the primary gatekeeper.

Architect and urbanist Pablo Sendra, alongside sociologist Richard Sennett, has explored how participatory systems fail when they simulate openness without enabling actual influence. The translation of civic processes into interface elements—the comment box, the vote button, the feedback map—can either democratize decision-making or reduce it to symbolic input.

Researcher Chris Speed’s work in digital place-making shows how design choices affect local agency. Interfaces can foreground community narratives, or they can abstract them into datasets. They can amplify local knowledge, or flatten it in the name of efficiency. The UI becomes a mediator between public values and institutional workflows. Net art pioneer Olia Lialina offers another important legacy. Her advocacy for the expressive, empowered “user” stands as a counter-model to contemporary platforms that treat individuals as endpoints. Civic interfaces that draw from this lineage expand agency; those that ignore it risk eroding it. In each case, design decides which publics count.

Designing Power: Toward More Negotiable Systems

When governance moves into the interface layer, design gains new responsibilities. Interaction patterns become policy instruments. Screen flows become behavioral constraints. Defaults become political positions.

The challenge is not to eliminate this power—governance is unavoidable—but to design for systems that remain legible, adjustable, and open to critique. For decentralized networks, that means interfaces that expose rather than conceal complexity, allowing communities to renegotiate structures. For corporate platforms, it means acknowledging that privacy, security, and agency are shaped through design decisions, not legal disclaimers. For civic systems, it means building UI architectures that expand—not compress—public influence. Interfaces are no longer front ends. They are governance engines. And as more decisions migrate into digital systems, designers increasingly shape the rules of engagement. The future of governance will be built in screens, flows, and interaction models. The question is whether we build them with accountability—or simply inherit them as default infrastructure.