By the time an image of Pope Francis strutting in a Balenciaga-style puffer coat lit up social feeds in 2023, the damage was done. Millions scrolled, shared, and liked before realizing the photo wasn’t real—it was generated by Midjourney’s AI. Verification didn’t fail. Verification is simply obsolete.

As generative AI annihilates the cost of producing plausible media, the crisis isn’t just technological—it’s epistemological. Trust, authorship, and perception are destabilizing. But while most of us scramble to keep up, a vanguard of artists and designers are prototyping ways to navigate a reality where truth is both infinitely reproducible and infinitely unstable.

Designing Doubt

In 2019, artist Mark Farid lived inside someone else’s life for two weeks, wearing a VR headset streaming first-person footage from a stranger’s camera glasses. Seeing I wasn’t conceived as a response to deepfakes—it preceded their viral breakout—but its premise nailed the psychological stakes: prolonged exposure collapses skepticism. If you see something long enough, your brain accepts it.

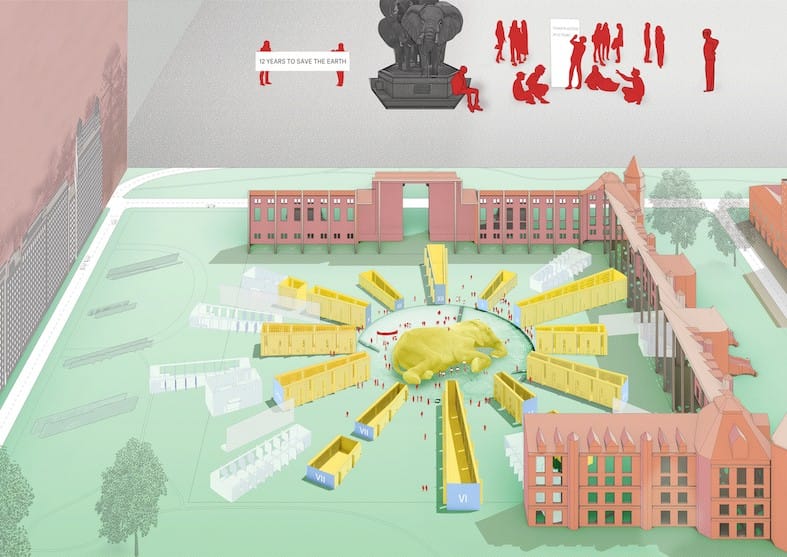

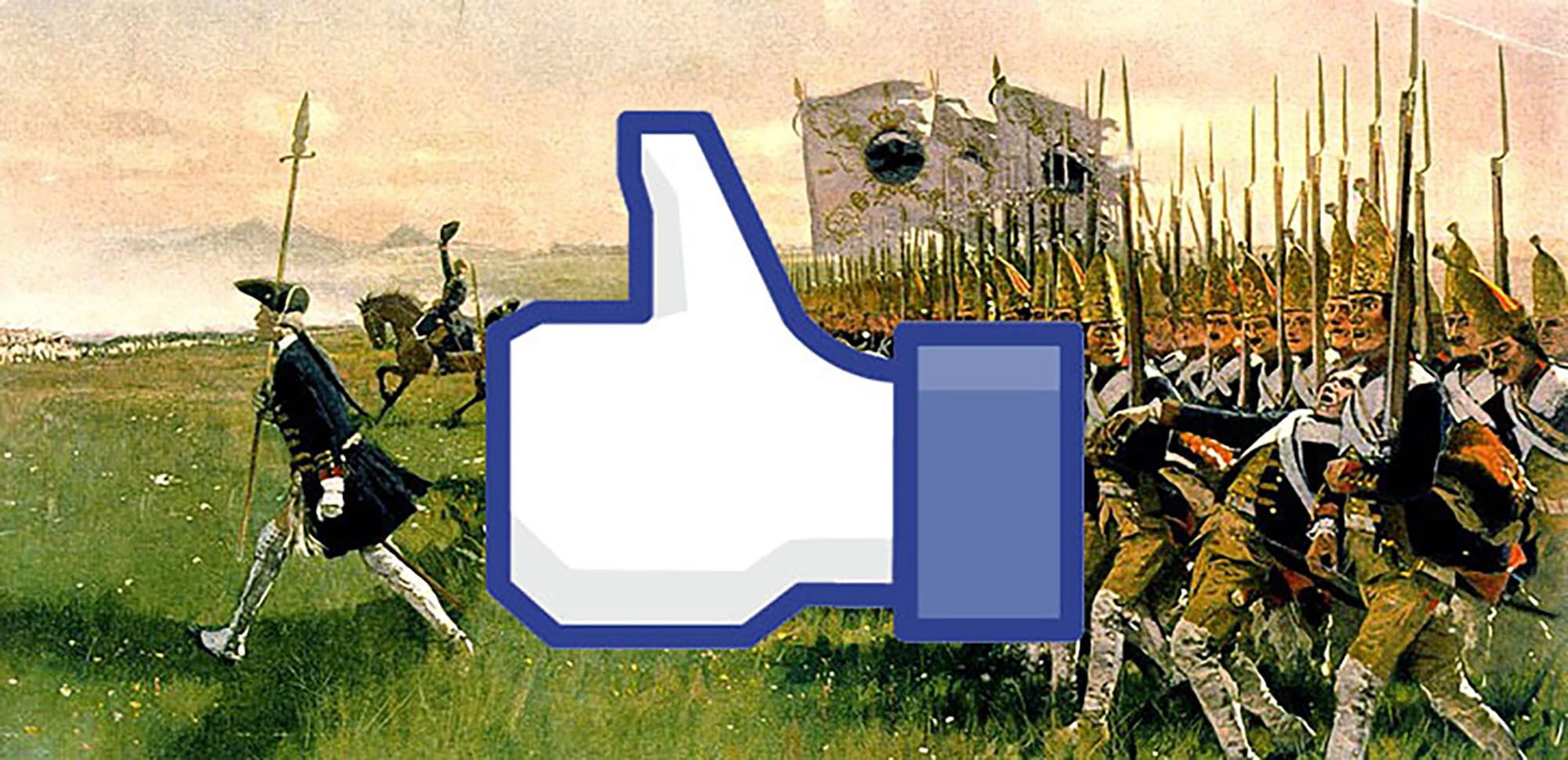

Long before Midjourney or Sora, Constant Dullaart’s The Possibility of an Army (2015) exposed another facet of synthetic consensus. He created 1,000 fake Facebook accounts based on the names of 18th-century Hessian soldiers. The bots weren’t powered by neural nets; they were strategically injected into social networks to simulate mass agreement—demonstrating how belief can be engineered algorithmically without ever generating a single convincing face. Sometimes, it doesn’t take deep learning. Just enough likes.

The Design of Plausibility

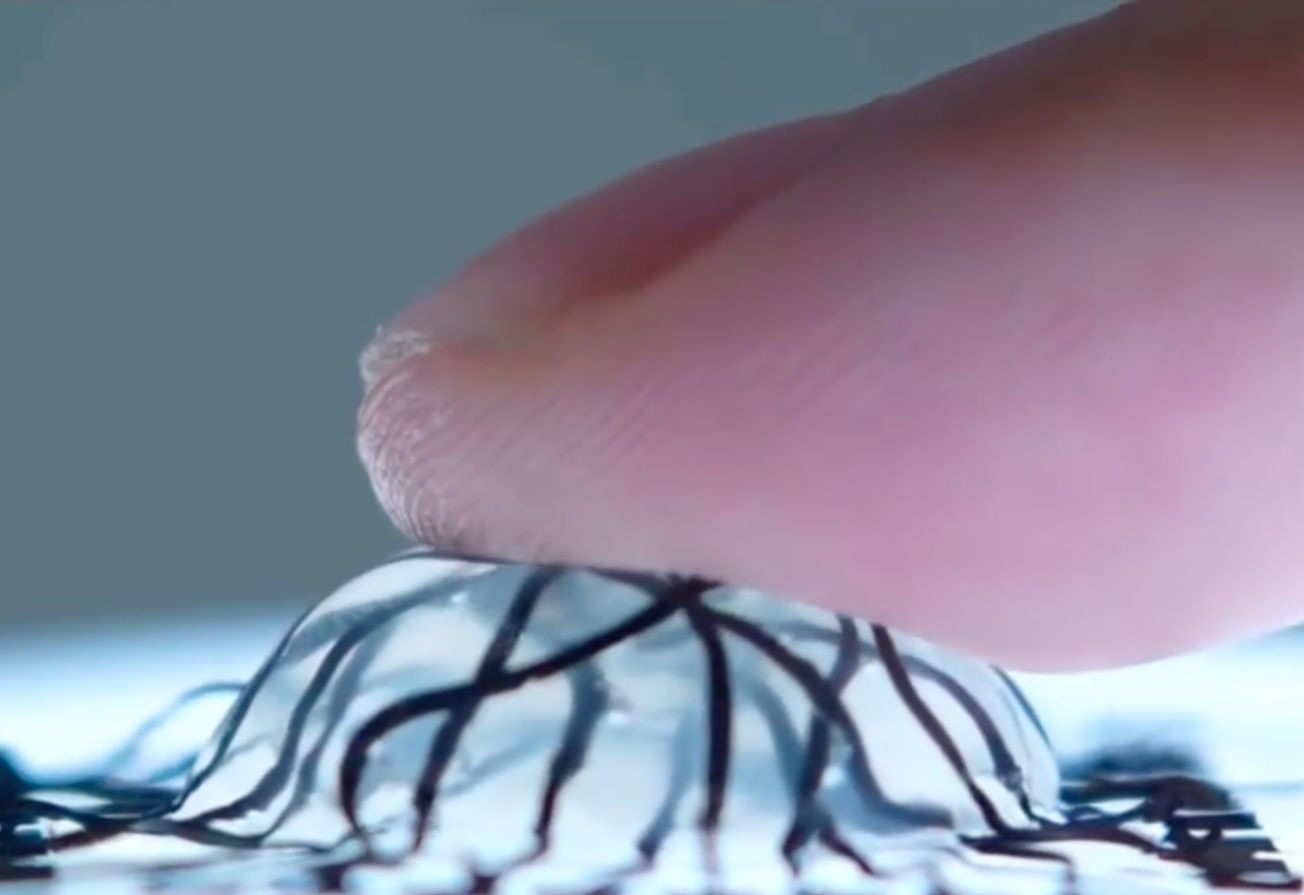

The illusion doesn’t always begin with images—it starts in the body. In What Shall We Do Next? (Sequence #2) (2014), Julien Prévieux choreographed patented touchscreen gestures—pinch, swipe, tap—as abstract movement, detached from any device. The performance exposes how interface design standardizes human gestures long before we’re conscious of it.

That same vocabulary now feeds AI training sets capturing gestures, micro-expressions, and embodied interaction—raw data for machine mimicry. What feels “natural” is often simply what’s been patented, licensed, and trained into algorithms.

Cracking the Black Box

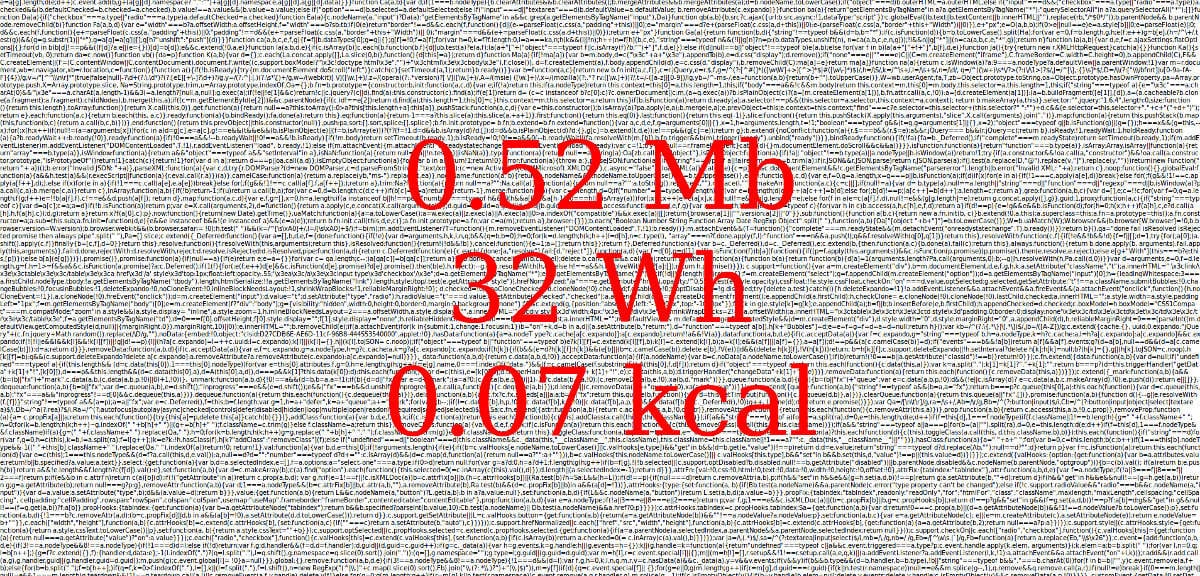

One counter-strategy: expose the machine’s inner workings rather than hiding them behind frictionless UX. Joana Moll’s The Hidden Life of an Amazon User (2019) dismantles the seamless veneer of e-commerce by visualizing over 1,300 background scripts triggered during a simple product search. The result is forensic: every data request, cookie, and tracker laid bare. Surveillance capitalism isn’t subtle—it’s just buried in plain sight.

Poet and coder Allison Parrish takes a similar approach with language. Her Compasses project procedurally remixes directional phrases—east, west, toward, beyond—generating texts that are at once patterned and absurd. The seams of generative language are left fully visible, revealing how algorithms simultaneously imitate and distort human syntax.

Configuring Authorship

If the 20th century worshiped originality, the 21st is embracing authorship as a curatorial, distributed act. Ross Goodwin’s 1 the Road (2018) exemplifies this shift: as he drove from New York to New Orleans, a neural network generated a novel in real time, fed by sensors, GPS data, and external inputs. The resulting text is fragmented, erratic, and strangely poetic—a co-authored record of experience between human and machine.

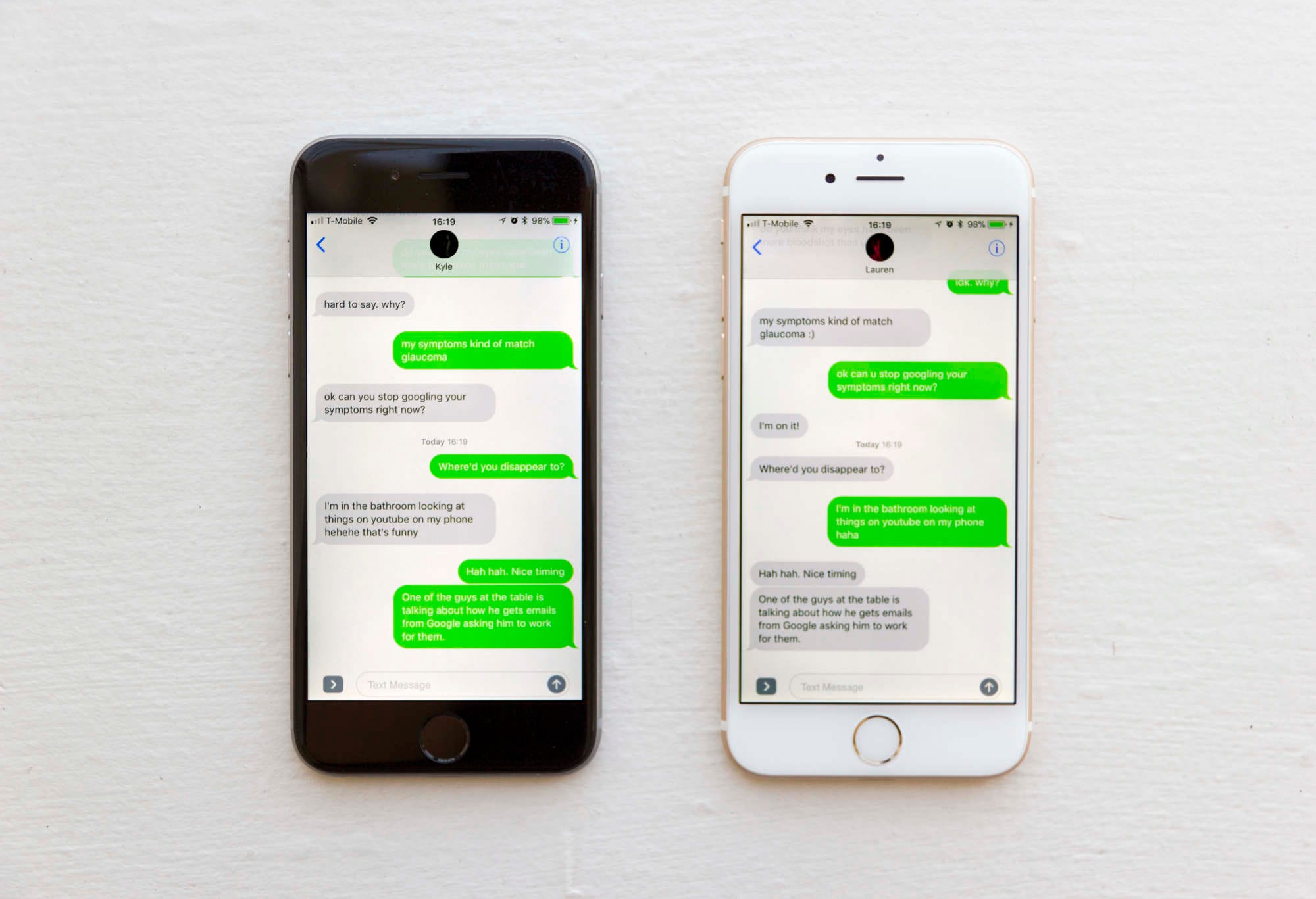

Kyle McDonald explores a different kind of generative authorship with MWITM (Man/Woman in the Middle). Collaborating with artist Lauren Lee McCarthy, McDonald created a system where two chatbots, trained on each artist’s conversational data, intercepted and mediated their phone calls in real time. The bots—functioning as generative stand-ins—blended human intention with algorithmic interpretation, raising unsettling questions about agency, authorship, and what it means to communicate through partially synthetic versions of ourselves.

After Verification

In the synthetic media arms race, the battle between real and fake isn’t just exhausting—it’s futile. Instead of trying to lock down truth, designers are pivoting toward conditions of negotiated belief. Trust becomes less about green checkmarks and more about contextual fluency: Who posted this? How is it framed? What semiotic cues suggest manipulation?

In this post-verification landscape, seamlessness is no longer the design ideal. Legibility is. The most relevant creators aren’t perfecting illusions—they’re teaching us how illusions function. Deepfakes won’t kill trust. But they will demand that we learn to see differently.