Designers and artists have long sought ways to give shape to the invisible—through maps, models, and diagrams that render abstraction legible. What distinguishes current practice is the deployment of digital fabrication, AI, and responsive systems to materialize datasets in physical form. From algorithmically generated textiles to kinetic sculptures and architectural installations, data is no longer confined to the screen but staged as something to walk around, touch, or inhabit. The move from intangible to tangible has always been fraught. Once translated into objects—whether 3D-printed forms, sculptural memorials, or built environments—datasets do more than visualize. They surface the infrastructures, assumptions, and politics that shape how information is collected and used.

From Code to Object

Early work established the lineage for today’s practice. Artists like Addie Wagenknecht and Golan Levin were less focused on literal “data sculpture” than on making invisible digital systems perceptible. Wagenknecht’s practice, spanning robotics, open-source fabrication, and handmade processes, exposes how power and surveillance shape technological infrastructures. Levin, known for pioneering computational art and interaction design, created works that reveal the inner logics of code and networks through visual and performative form.

While not always producing 3D-printed artifacts, both helped set the stage for thinking about how abstract systems could be embodied and scrutinized through design. Jer Thorp extended this trajectory with projects like Just Landed (2008), which transformed Twitter data into patterns of international movement. Though originally screen-based, Thorp also fabricated data into laser-cut and 3D-printed artifacts, demonstrating how datasets could be confronted as objects rather than fleeting graphics.

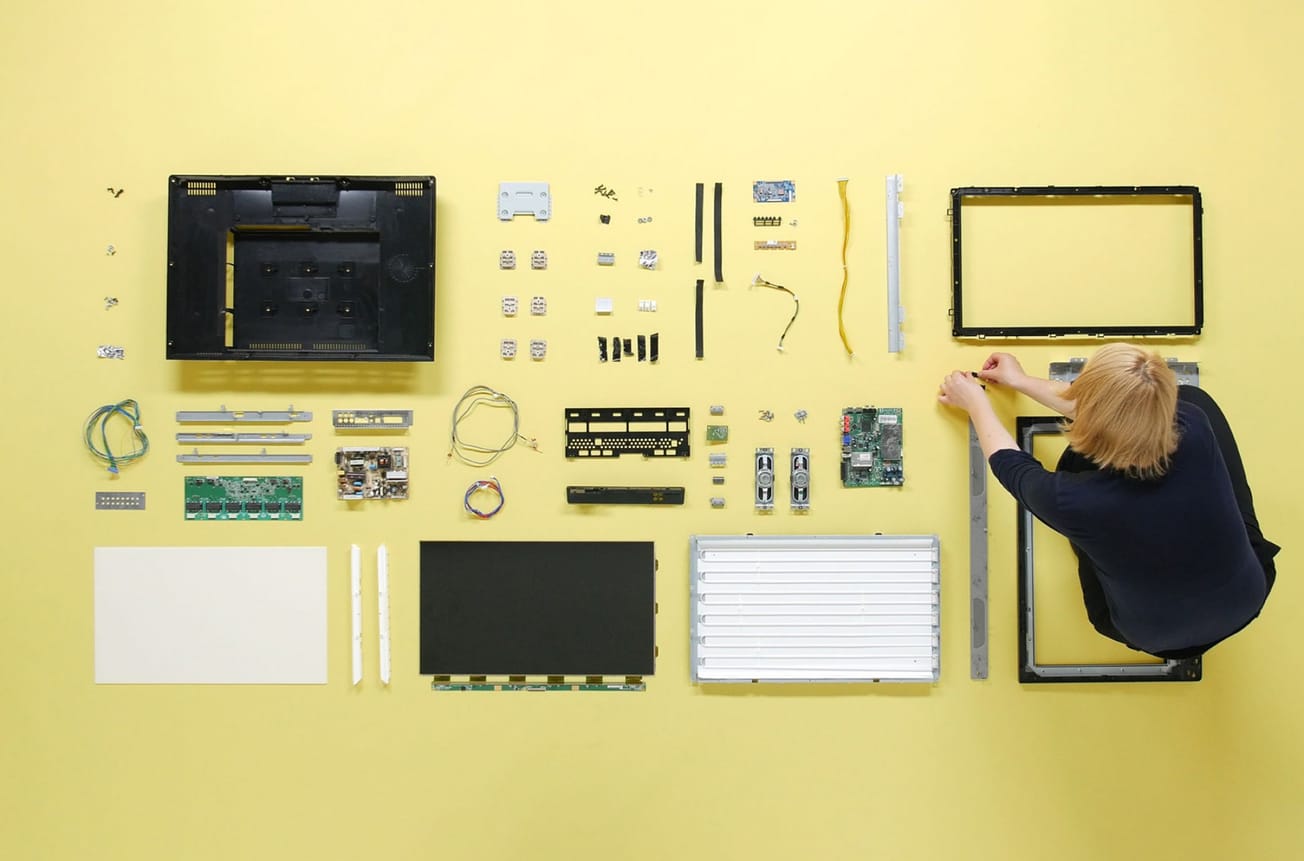

Formafantasma’s Ore Streams (2017–19) reframed the conversation. Instead of visualizing numerical datasets, they worked with e-waste materials to expose the infrastructures of digital culture. Here, the material itself is the data: the flows of minerals, plastics, and discarded electronics that underpin technological systems. Nervous System, the Massachusetts-based studio of Jessica Rosenkrantz and Jesse Louis-Rosenberg, carried this ethos into generative design. Their Kinematics series (2014 onward) simulated folding and movement in 3D-printed textiles, embedding computational logic directly into wearables.

Matthew Plummer-Fernandez’s Disarming Corruptor (2013) took a more critical approach, distorting and encrypting printable files to expose the cultural politics of digital fabrication. And Shinseungback Kimyonghun’s Cloud Face (2012) turned facial recognition errors into tangible artifacts, materializing the flaws of AI vision systems.

Together, these works set the foundation: treating data not only as information to be displayed but as a material to be shaped, embodied, and critiqued.

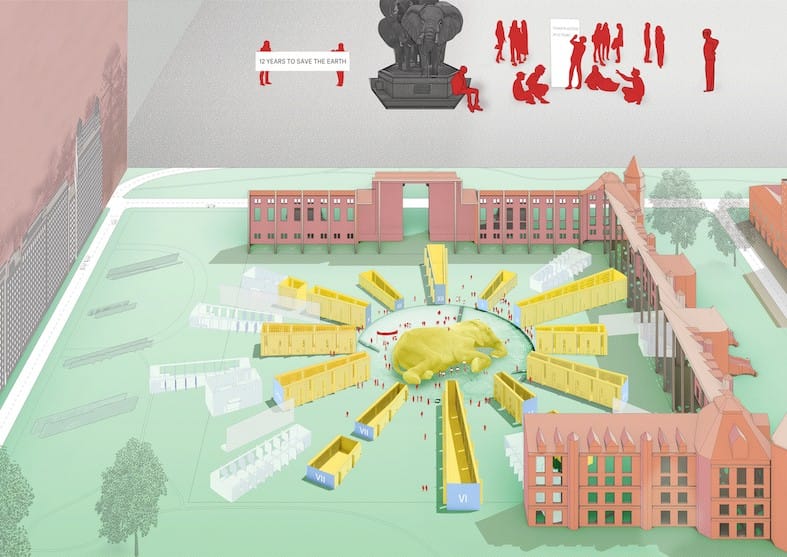

Expanding the Field, 2023–25

Recent years have seen a resurgence of interest in making data tangible, driven by advances in fabrication, sustainability concerns, and new cultural questions about AI and infrastructure.

At Oregon State University’s PRAx building, Data Crystal: OSU (2024) by Refik Anadol transforms 10,000 hours of forest audio collected by an array of 1,200 microphones into a crystalline, AI-generated sculpture. Rather than printing datasets, the project uses algorithmic translation to turn ecological monitoring into a physical presence in the lobby, collapsing sound into sculptural form.

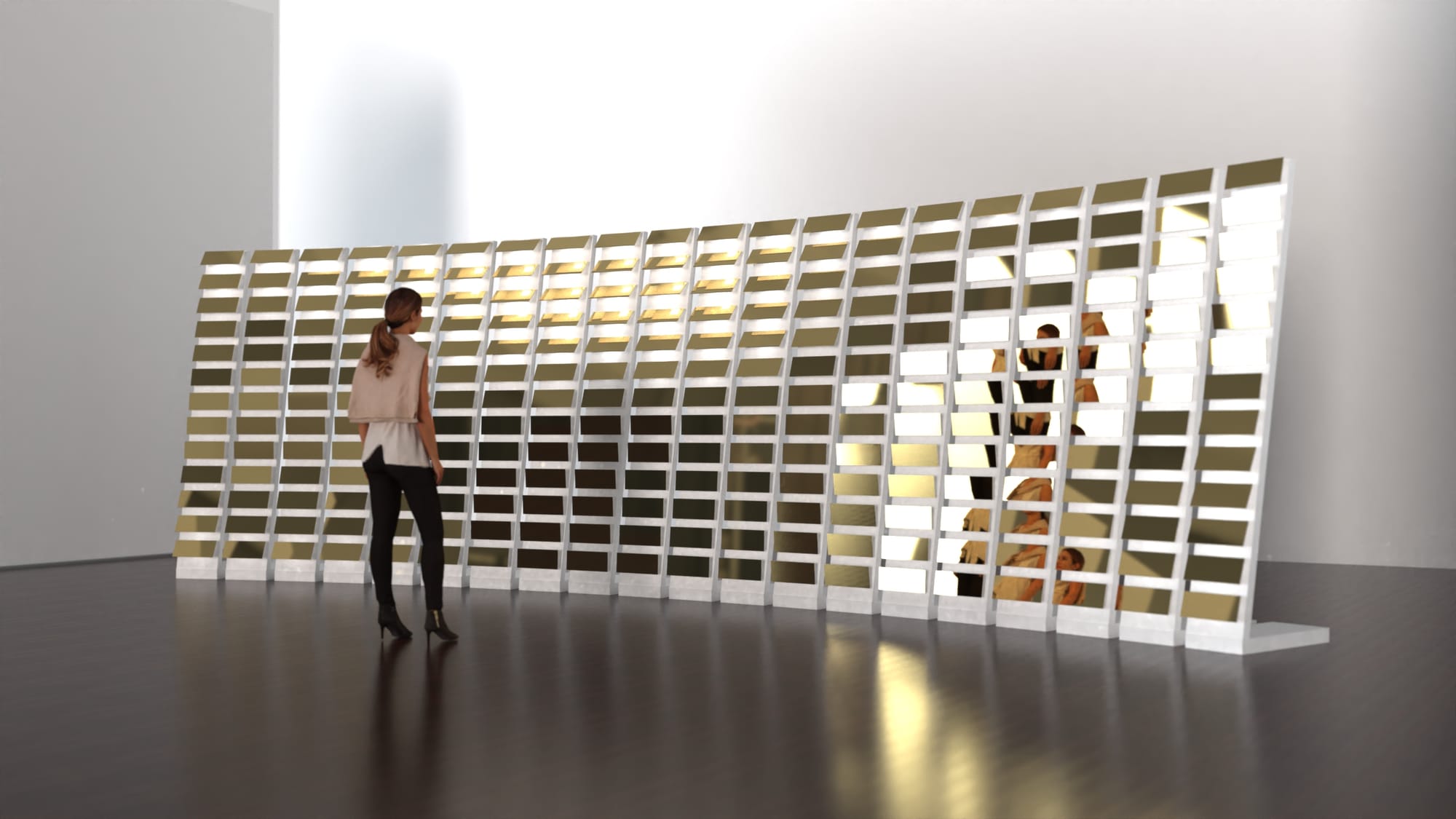

At Art Dubai 2025, BREAKFAST unveiled Carbon Wake, a monumental kinetic installation driven by real-time energy consumption data from more than 100 cities worldwide. Thousands of mirrored tiles shift in rippling waves, responding to fluctuations in fossil fuel use and renewable output. The sculpture turns the abstraction of carbon dependency into a dynamic, visceral experience of global infrastructure.

The architectural scale is evolving too. The null² pavilion, designed by Yoichi Ochiai with NOIZ for Expo 2025 in Osaka, integrates mirrored membranes, robotic actuation, voxel-like structures, and acoustic vibrations. While not a dataset in the conventional sense, the pavilion itself is a real-time materialization of “digital nature,” where robotic systems and visitor interactions produce a constantly shifting environment.

Sustainability has also become central. Rain Gauge (2024, University of Minnesota) 3D-prints 80 years of precipitation data in ceramic form, each month projecting outward on a cylindrical surface. By replacing plastics with clay, the project foregrounds the ecological footprint of physicalization itself. Similarly, IAAC’s 3D-Printed Earth Forest Campus (2024, with Crane WASP) uses local soil and fibers in large-scale robotic printing. Here, environmental performance data is not visualized but embedded in the fabrication process itself, aligning construction with material circularity and site conditions.

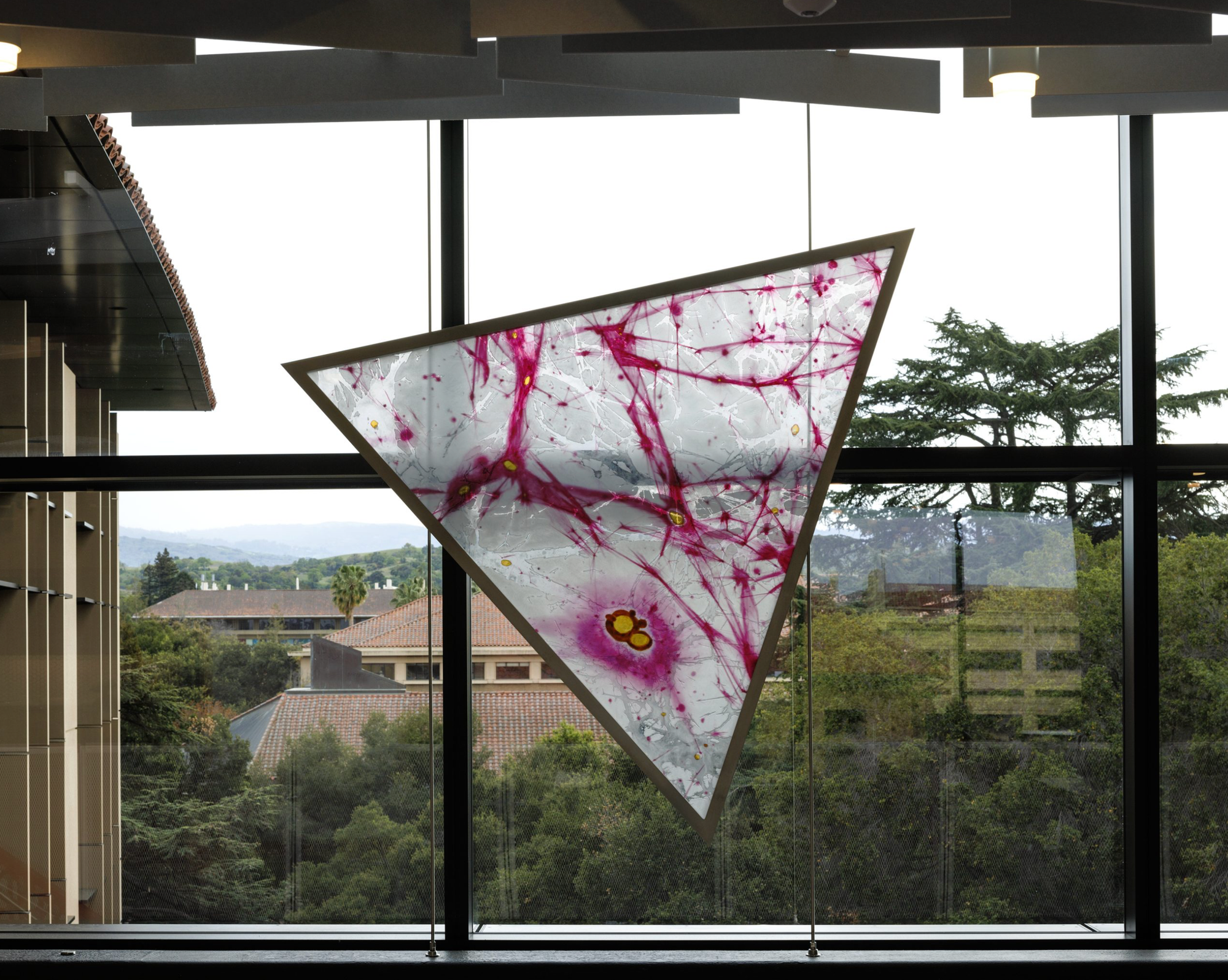

Finally, institutional installations are embedding data physicalization in educational spaces. At Stanford’s CoDa building, Camille Utterback’s Fathom (2025) creates an interactive installation tracing the history of encoded data. Panels and light-responsive surfaces let visitors explore how information has been recorded across time, turning abstract information theory into a tactile museum experience.

From Abstraction to Weight

What unites these projects is not a single medium but a shared strategy: making abstract systems tangible. Whether the subject is rainfall, energy infrastructure, forest soundscapes, or computational folding, physicalization transforms the immaterial into something you can hold, enter, or stand before.

This shift is more than aesthetic. By materializing data, designers expose its infrastructures, politics, and costs. Formafantasma’s Ore Streams reveals the material afterlife of electronics, exposing the infrastructures and supply chains embedded in every device. BREAKFAST’s Carbon Wake translates the world’s carbon dependency into a moving surface of kinetic tiles. Rain Gauge questions the ecological footprint of fabrication itself. And Data Crystal reframes environmental monitoring as cultural object.

As data grows ever more pervasive, the ability to translate it into matter is becoming a critical form of design literacy. These materializations do not only communicate information—they reshape our relationship to the systems we build and inhabit.