Buildings account for nearly 40 percent of global carbon emissions—more than aviation and shipping combined. For years, architectural “innovation” has leaned on high-performance glass façades, algorithmic skylines, and smart systems promising optimization. Yet the projects that now look most advanced don’t resemble gleaming towers or sensor-packed campuses. They look almost primitive: walls of mud, structures cooled by natural airflow, houses pieced together from salvaged timber and brick.

The paradox is that methods once dismissed as backward are proving to be among the most credible tools for designing in an age of climate constraint. Across the globe, architects are using digital fabrication not to escape vernacular traditions but to extend them—scaling local knowledge, circular materials, and low-energy systems into the mainstream of design. Low-tech, it turns out, may be the sharpest form of innovation.

Climate Logic, Scaled

Francis Kéré’s buildings in Burkina Faso show how climate performance can be achieved without mechanical cooling or imported infrastructure. Clay walls and carefully positioned apertures regulate air and temperature, while construction is carried out by local communities. These are civic structures built from the ground up—literally.

London-based Material Cultures pushes that same logic into industrialized contexts. Led by Paloma Gormley, the studio works with hemp, straw, and timber to create modular systems that can scale into housing and infrastructure. Their proposition is blunt: if construction keeps relying on steel and concrete, it locks in planetary failure.

By reframing agricultural byproducts as credible replacements for carbon-heavy materials, Material Cultures positions “low-tech” as a viable industrial strategy, not just an artisanal experiment. Together, Kéré and Material Cultures demonstrate that climate-responsive architecture doesn’t require exotic technologies. It requires aligning design intelligence with what is already abundant—soil, straw, and labor—and treating them as assets rather than limitations.

Reuse as Cultural Technology

If materials are one axis of the low-tech turn, adaptive reuse is another. Assemble Studio’s Granby Four Streets project in Liverpool revived a neighborhood of derelict Victorian terraces through collective repair. Working with the Granby Four Streets Community Land Trust, the group salvaged building elements and developed Granby Workshop, which produces hand-made tiles, fireplaces, ceramics, and furnishings from reclaimed and locally sourced materials. These were not just technical fixes but became central to the project’s aesthetic—patchwork surfaces and visible joins that celebrate repair.

Reuse here isn’t simply about carbon savings. It operates as a cultural technology—redistributing authorship and making construction a shared civic act. Assemble’s approach turns neighborhoods into producers of architecture, not passive consumers of glossy development. The design language is imperfect, sometimes messy, but deliberately so: resilience made visible.

Speculative Vernaculars

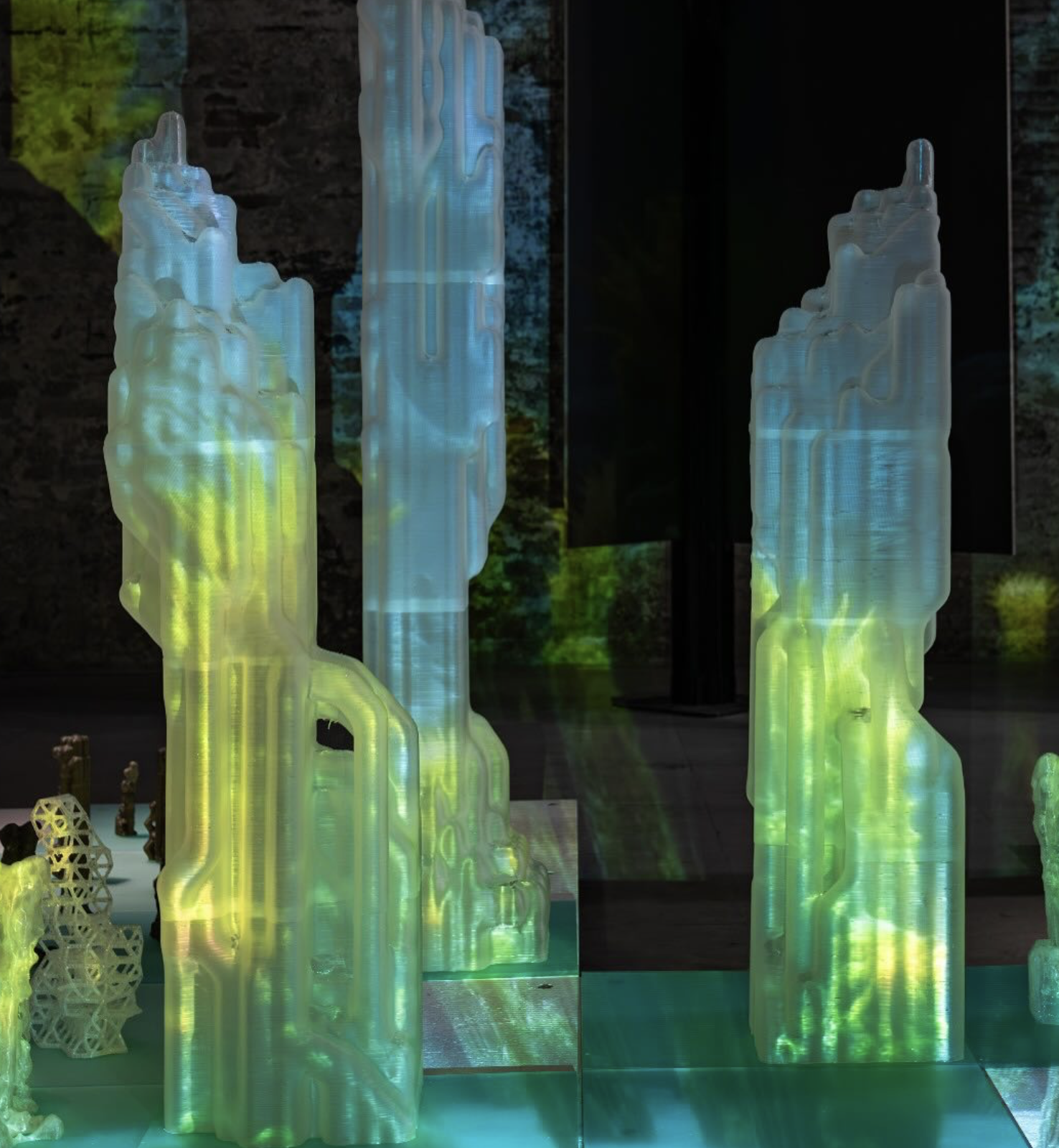

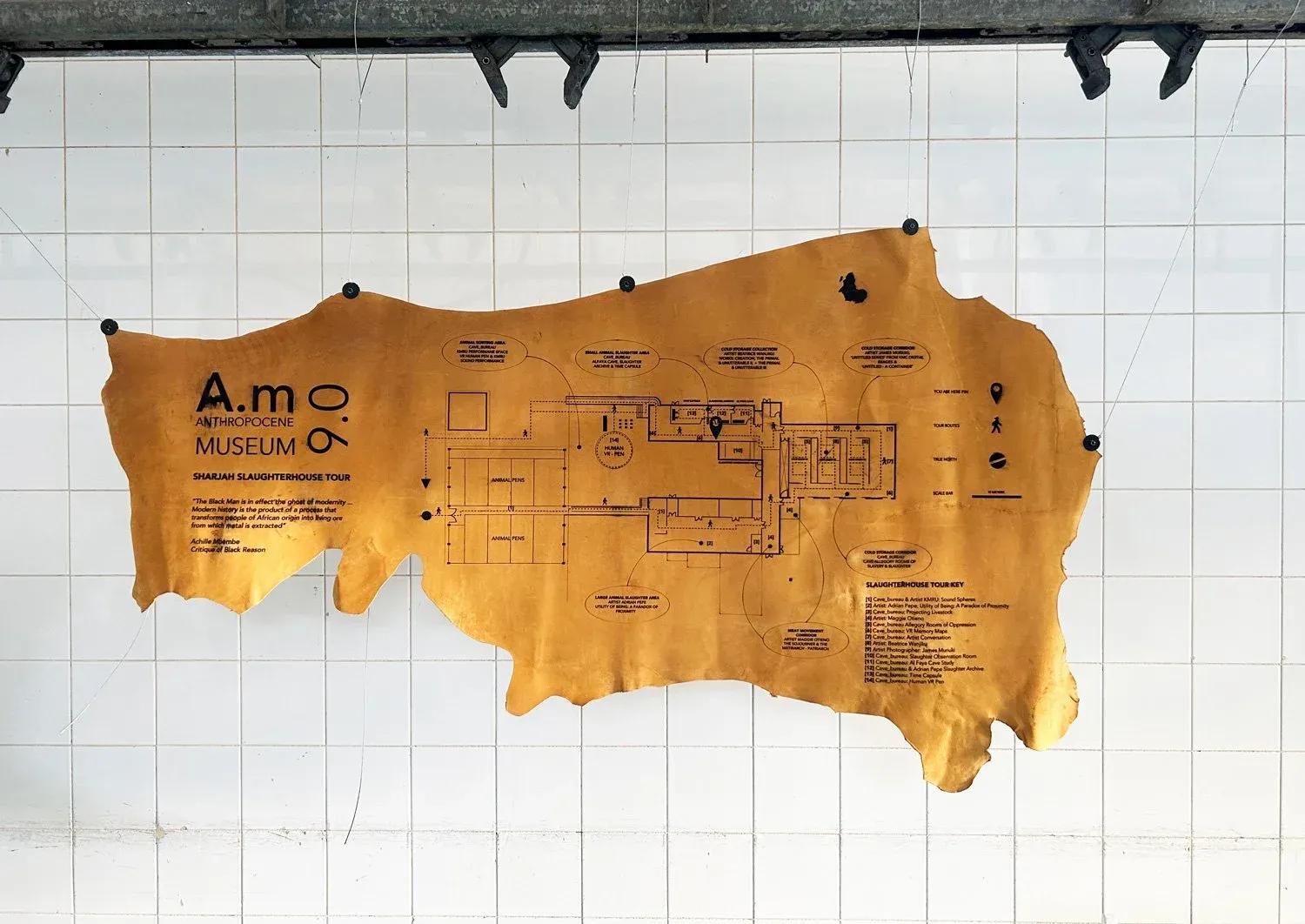

Other practices are pushing low-tech into speculative territory. Nairobi-based Cave_bureau—founded by architects Kabage Karanja and Stella Mutegi—works directly with geological and indigenous knowledge systems. Their ongoing Anthropocene Museum project, staged in natural caves such as the Nairobi Lava Tube, positions the cave as both the oldest form of architecture and a lens for imagining post-carbon futures. By combining oral histories, spatial installations, and field research, Cave_bureau reframes “low-tech” as a design intelligence rooted in deep time.

Meanwhile, TRAME, a studio based in Paris, TRAME, a Paris-based studio founded by Ismail Tazi, uses computational tools to extend craft traditions, particularly those rooted in Moroccan heritage. Digital weaving and parametric modeling are paired with artisanal techniques and local materials, producing hybrid works that resist the binary of tradition versus technology. Their practice suggests that digital fabrication doesn’t have to erase vernacular knowledge; it can scale and adapt it to contemporary needs.

Together, Cave_bureau and TRAME demonstrate that low-tech futures are not monolithic. They can be speculative, computational, or indigenous—but always grounded in situated knowledge rather than imported templates.

Redefining Innovation

The throughline across these projects is a redefinition of innovation itself. Glossy façades and sensor-packed systems may still dominate architectural marketing, but the more consequential work is happening elsewhere: in buildings that breathe naturally, in materials that regenerate rather than deplete, in neighborhoods that organize around repair, in traditions recalibrated through digital tools.

Low-tech is not nostalgia. It’s a design frontier that privileges continuity over novelty, resilience over spectacle. And for architects still chasing skyscrapers and “smart cities,” the provocation is stark: if the future of architecture is low-tech, what happens to those who refuse to step off the high-tech escalator?