Adaptive reuse, once a niche preservationist tactic, has become a key strategy in architecture’s climate adaptation playbook. But this isn’t just about recycling buildings. It’s about reorienting design around restraint, intuition, and local intelligence. It’s about asking, What if we already have everything we need?

Resilience by Design

In the hills of Baskinta, Lebanon, a prototype home rises from the landscape like it’s always been there. Designed by architect Nizar Haddad, Lifehaus is a radical experiment in ecological self-sufficiency—built without concrete, steel, or synthetic insulation. The structure is composed of earth-packed car tires, sun-dried clay bricks, stones gathered on-site, and sheep’s wool harvested from nearby flocks. Recycled materials form the bones of the building. A greenhouse wrapped around its southern face generates passive heat and food. Solar panels provide energy, rainwater is harvested, and greywater is filtered through reed beds.

There are no smart sensors here. No app-controlled systems. And yet Lifehaus functions with a quiet precision that outpaces many “high-performance” buildings. Its design pulls from the past—vernacular mountain architecture, off-grid ingenuity—and folds it into a low-carbon, regenerative blueprint for the future. It’s not architecture as monument, but as metabolism.

Across the globe, this ethos is gaining traction. In Yazd, Iran, ZAV Architects are reviving desert construction methods to create modern forms of communal housing that cool themselves through thermal mass and air flow, not mechanical systems. Their projects, such as Presence in Hormuz 2 (Majara Residence) by ZAV Architects use local brick and traditional techniques not as aesthetic flourishes, but as climate strategy—affordable, scalable, and radically sustainable.

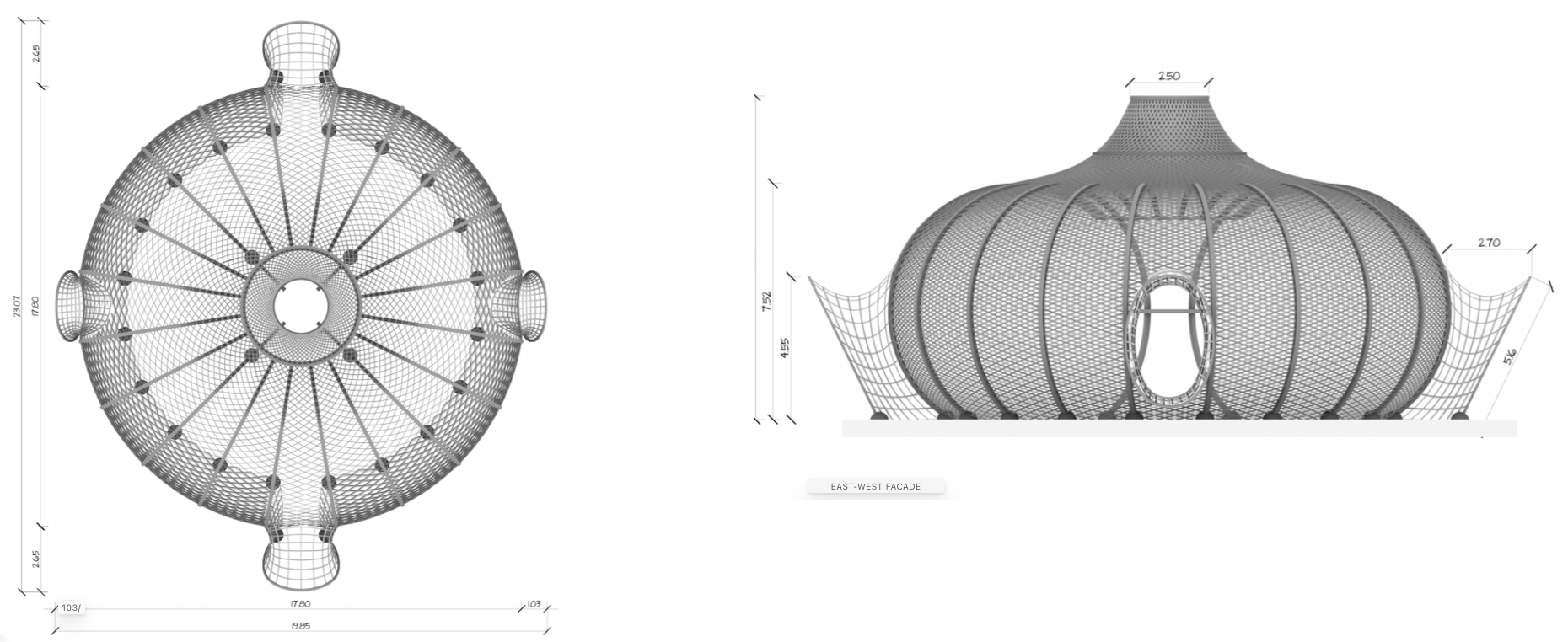

And in rural Colombia, Fundación Organizmo trains local communities to reconstruct collapsed colonial buildings using wattle and daub, adobe, and rammed earth. Their work bridges ancestral craft with environmental resilience, reframing architecture as both social practice and material repair. One standout example is the House of Thought, a circular structure co-built with Indigenous leaders using local bamboo, earth, and lime, designed to host intercultural dialogue and environmental education. Its form and materials reflect a philosophy of reciprocity—between people, place, and the land that sustains them.

These buildings don’t perform in spite of their simplicity. They perform because of it.

The Architecture of Enough

What defines low-tech design isn’t just what it uses—but what it refuses. Extruded aluminum. Foam insulation. Fossil-fueled HVAC. The low-tech approach prioritizes local materials, passive energy systems, modularity, and manual labor. It’s a design language that values care over speed, legacy over novelty.

This is not about going backward. It’s about moving forward differently—scaling down to scale impact. Rather than obsessing over net-zero buildings built from rare-earth materials, low-tech designers ask: What if we got to zero by doing less?

In the Netherlands, Zecc Architecten took this idea to brutalist heights—converting a defunct 1960s water tower in Utrecht into a vertical residence. They left its raw concrete intact, threading wood, steel, and light through its core. The result is stark, beautiful, and efficient—preserving the tower’s embodied energy while radically altering its purpose.

These projects aren’t anomalies. They’re signals of a shift in architectural consciousness. As cities age and climate pressure mounts, the most resource-rich construction sites are not empty lots—but forgotten buildings. Deconstruction ordinances in cities like Portland, Oregon, now mandate that older buildings be dismantled for salvage rather than demolished, pointing to a future where “material banks” could replace landfills as the default endgame for architecture.

Memory as Infrastructure

The real power of adaptive reuse lies in its capacity to preserve memory—not as nostalgia, but as infrastructure. When buildings are reused rather than replaced, they retain more than just carbon. They retain context. Culture. Continuity. They become vessels for layered meaning, not blank-slate ambition.

In this light, architecture shifts from a commodity to a commons. It becomes iterative, participatory, and regenerative. And it points to a future where construction is measured not by speed or scale, but by stewardship.

Low-tech design does not mean low aspiration. If anything, it demands more from its creators: more attention, more sensitivity, more time. But the payoff is profound. It offers a way to reimagine the built world not as a monument to extraction, but as a living system—flexible, local, and deeply attuned to the rhythms of the planet.

In the coming decades, the cities that thrive will be the ones that learn how to unbuild—gracefully, intelligently, and with care. Because the future isn’t something we need to construct. More often than not, it’s something we need to uncover, adapt, and inhabit more wisely.