The sound of the future is no longer entirely human. It's stitched together by code, informed by datasets, and increasingly indistinguishable from compositions written in bedrooms, studios, and symphony halls. As generative AI accelerates into music production, sound design, and live performance, the boundaries between machine and musician blur—not quietly, but audibly.

In 2025, AI-generated audio is both a creative experiment and a commercial disruptor. Tools like Suno and Udio allow anyone to generate radio-ready tracks with simple text prompts. Google’s MusicLM generates multi-instrument compositions from written descriptions, while Meta’s AudioCraft suite enables fine-tuned control over timbre, rhythm, and genre through models trained on vast audio libraries. Stability AI’s Stable Audio 2.0 can now generate full tracks—including vocals—directly from prompts. Yet beneath this layer of instant generation lies a deeper, more complex evolution. Artists and designers aren’t simply using AI to automate production; they are interrogating sonic authorship, rethinking collaboration, and experimenting with entirely new modes of composition.

From Composition to Co-Creation

When early models like OpenAI’s Jukebox or Riffusion emerged, much of the attention focused on their technical prowess—recreating the voice of Elvis, simulating lost jazz recordings, or generating infinite ambient loops. But many artists quickly saw them not as tools of replication, but as collaborators capable of producing unexpected, even surreal creative outcomes.

Holly Herndon’s project PROTO (2019) is one of the most visible examples. She developed a custom AI vocal model, "Spawn," trained on her own voice and those of collaborators. Rather than outsourcing composition, Herndon treated the AI as a synthetic ensemble member—blending machine output with human performance. “It’s not about replacing humans,” she told Pitchfork, “it’s about augmenting human expression.”

Similarly, the LA-based band YACHT trained an AI model on their full discography to co-compose their 2019 album Chain Tripping. Lyrics, melodies, and cover art were all partially generated, with the band curating and editing the AI's unpredictable results. The process transformed glitches and misinterpretations into creative raw material.

Text-to-Music: From Prompt to Pop

As text-to-image generation surged into public consciousness through tools like DALL·E and Midjourney, music generation followed. In 2023, startups like Suno AI and Udio launched highly accessible text-to-music platforms. Users type prompts such as "futuristic synth-pop with glitchy percussion" or "lo-fi jazz ballad with rain ambiance" and receive fully produced tracks within seconds—complete with vocals, mastering, and radio-level fidelity.

For sound designers, advertisers, podcasters, and independent musicians, the implications are significant: high-quality custom audio at near-zero marginal cost. But these capabilities also raise difficult questions about authorship, licensing, and attribution—particularly since many AI models are trained on copyrighted recordings without artist consent. Legal frameworks are scrambling to catch up. Major labels have already filed lawsuits against AI platforms accused of training on protected works, echoing broader legal disputes over generative models across media industries.

Adaptive and Performative Sound

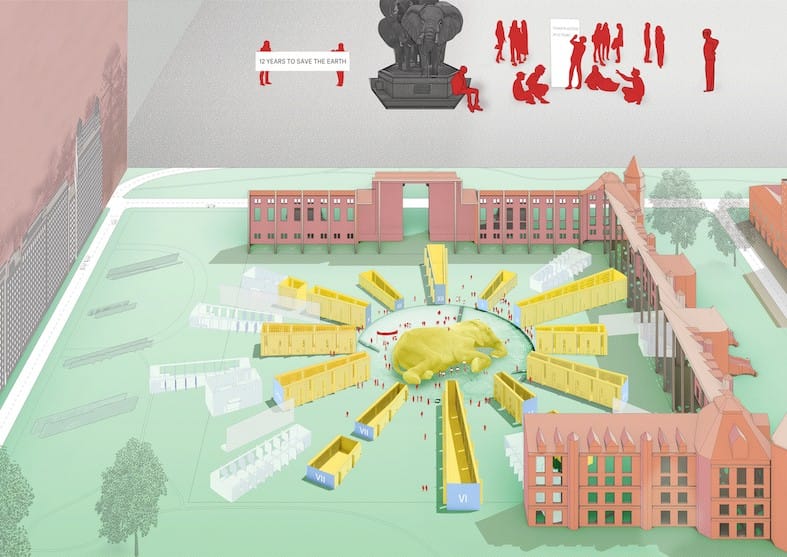

Beyond generating static tracks, AI is reshaping how sound responds in real-time. In gaming, generative soundtracks adapt to player behavior, creating dynamic music that evolves with narrative arcs and environmental changes. Startups are prototyping AI-powered adaptive scores for AR, VR, and spatial computing, allowing soundscapes to adjust fluidly based on user movement and sensor data.

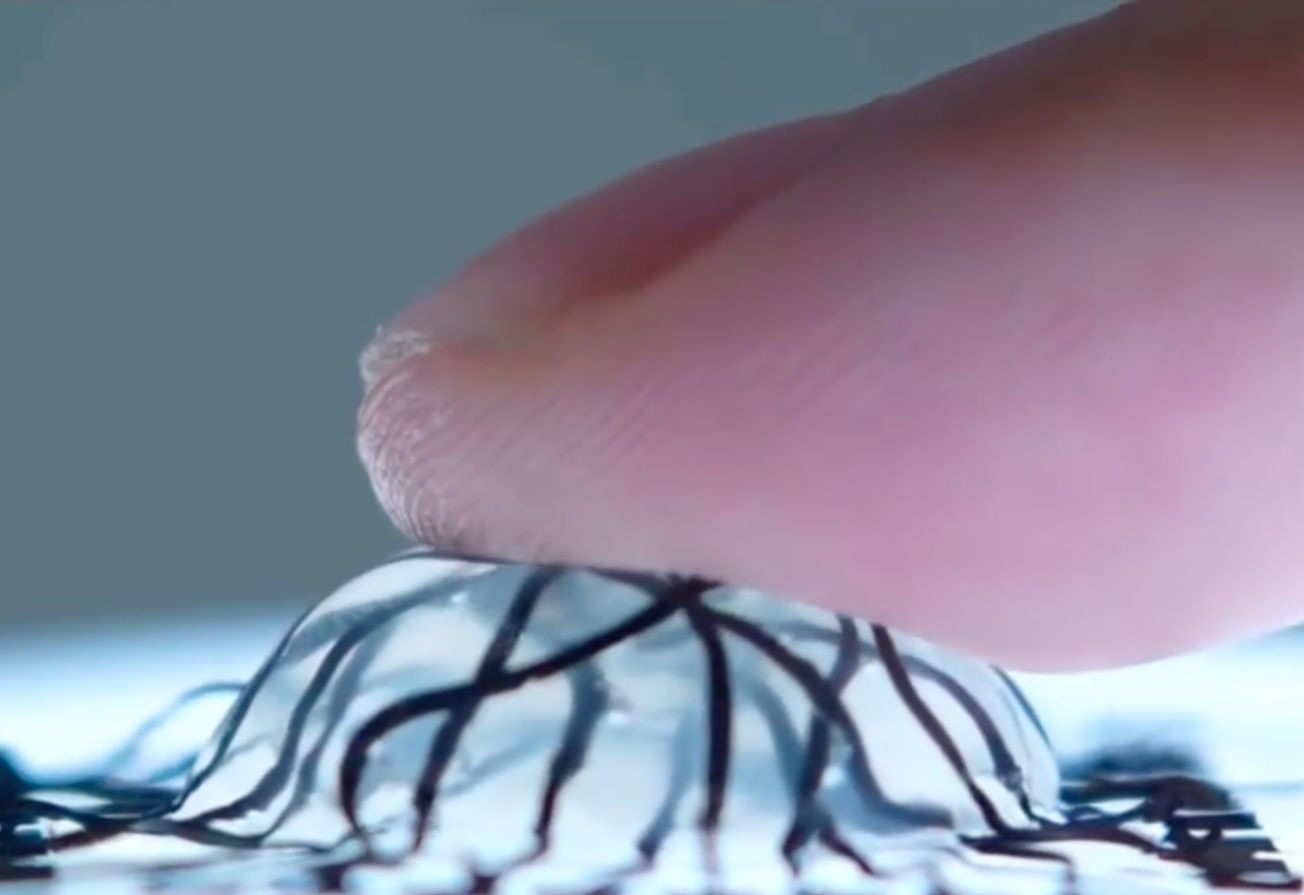

Several artists are pushing these concepts into performance art. In Symbiotic Rituals (2019), French artist Justine Emard collaborated with Alter 2 and Alter 3—humanoid robots co-developed by the Ikegami Laboratory at the University of Tokyo and the Ishiguro Laboratory at Osaka University—using deep learning algorithms that allowed the robots to respond to a dancer’s movements, generating live music and creating a real-time audiovisual feedback loop. Similarly, Anna Ridler’s Bloemenveiling (2020) combined GAN-generated visuals with AI-generated ambient audio, blending data-driven visuals and sound into an immersive installation.

Sonic Sovereignty and the Question of Identity

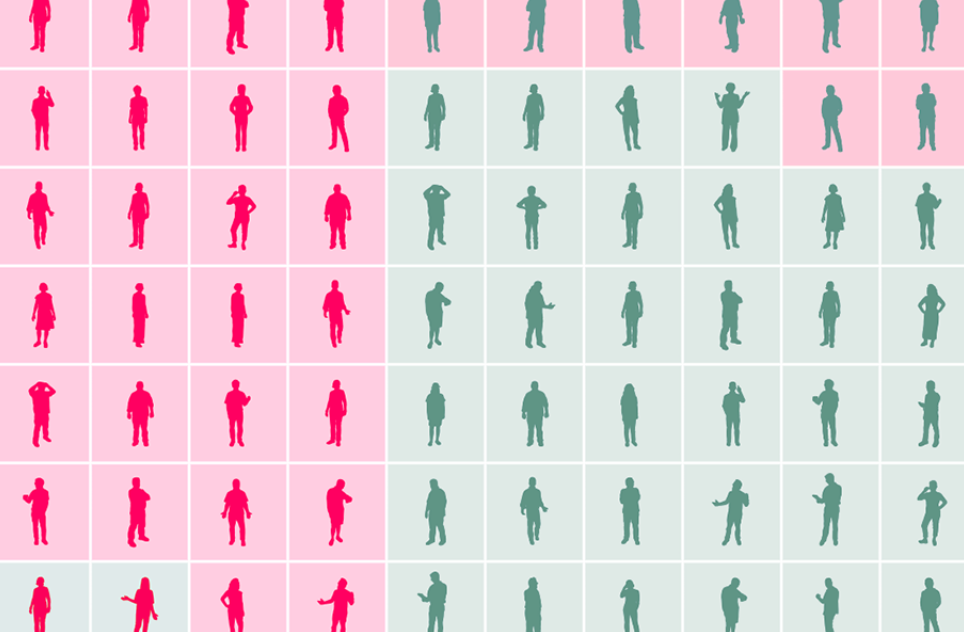

The viral spread of AI-generated tracks mimicking major artists—most notably Heart on My Sleeve (2023), which replicated the voices of Drake and The Weeknd—has sharpened concerns around sonic identity and ownership. As voice cloning tools proliferate, questions about vocal rights, stylistic ownership, and ethical licensing have become central debates.

Some artists have taken divergent approaches. Grimes, for example, has openly licensed her AI-generated voice under specific conditions, while others have actively fought against unauthorized clones. The right to control one’s sonic likeness—what some researchers call sonic sovereignty—is quickly becoming a contested legal frontier. Projects like James Coupe’s General Intellect (2021) explore these questions from a critical art perspective, blending synthetic speech and human narration to challenge assumptions about authenticity, gender, and voice identity in machine-mediated sound.

Labor, Scarcity, and the Collapse of the Stock Music Industry

The commercial implications extend beyond rights management. Traditional stock music libraries are facing disruption as platforms like Mubert, Soundful, and Amper Music offer infinite, customizable soundtracks on demand. For small studios and creators, these tools dramatically lower costs. For freelance composers and sound designers, they introduce new competition that automates significant portions of mid-tier production work. While high-end scoring for films, games, and complex narratives will still require human expertise, AI is increasingly taking over low-budget and rapid-turnaround projects, reshaping the economics of creative labor. At the same time, some see these tools as expanding access rather than replacing artistry. As AI lowers production barriers, more creators can experiment with professional-grade sound design without requiring technical expertise or expensive studio access.

Synthetic Audio’s Expanding Frontier

Major tech platforms are aggressively advancing generative audio. Google’s AudioLM operates directly on audio tokens, capturing fine-grained aspects of rhythm, timbre, and dynamics. Meta’s AudioCraft suite is expanding to handle longer, higher-fidelity compositions. Stability AI’s Stable Audio continues refining prompt-based composition pipelines. Meanwhile, these models are increasingly being applied to adjacent domains: voice cloning, dubbing, accessibility tech, misinformation, and psychological influence operations. Synthetic audio is also converging with synthetic media more broadly. Just as deepfakes have destabilized trust in images and video, AI-generated voices and music introduce subtler, harder-to-detect manipulations that could shape public discourse, politics, and personal identity.

Redefining Sonic Futures

AI’s technical breakthroughs in generative sound are undeniable. But their long-term social, cultural, and political impacts remain deeply unsettled. The ability to generate highly convincing soundscapes challenges not just the music industry but cultural notions of creativity, labor, ownership, and even human identity.

As synthetic sound becomes normalized across entertainment, advertising, social media, and live performance, the central question isn’t whether AI will transform sonic culture—it already has. The question is who will ultimately control that transformation: artists, developers, platforms, regulators, or audiences themselves. The future of music isn’t fully automated. But it is undeniably synthetic.