The phrase “post-digital craft” is often misread as retreat—a soft-focus return to hand tools and pre-industrial methods. In practice, it signals something more structural: a recalibration of making after digital tools became default infrastructure. Post-digital craft does not reject computation. It absorbs it, retools it, and insists that technique, material intelligence, and embodied judgment still matter—even when the tools are robotic arms and parametric scripts.

As AI-generated imagery saturates feeds and manufacturing pipelines grow increasingly automated, a countercurrent is visible across design studios and fabrication labs. Authors are not abandoning machines. They are relocating authorship into systems—into parameters, toolpaths, calibration routines, and fabrication protocols. The result is hybrid practice: neither analog revival nor techno-optimism, but materially grounded and computationally fluent.

Hybrid Making After Automation

Digital fabrication expanded rapidly in the 2010s. Fab labs and makerspaces standardized access to CNC routers, laser cutters, and desktop 3D printers. That expansion democratized production—but it also normalized a recognizable visual language: parametric surfaces, algorithmic lattices, and toolpath aesthetics. Post-digital craft begins after that normalization. The machine is no longer the spectacle. The focus shifts to tuning—surface behavior, movement, structural performance—through iterative testing rather than frictionless output.

Amsterdam-based Studio Drift exemplifies this shift. Founded by Lonneke Gordijn and Ralph Nauta, the studio builds kinetic installations that combine custom engineering with material experimentation. Their work Shylight unfolds and retracts in sequences inspired by nyctinasty, the movement of flowers. The installation relies on precisely calibrated mechanical systems, yet the perceptual effect emphasizes timing, sensitivity, and variation. Technology functions as a tuned instrument rather than a productivity engine. The emphasis is not on speed or scale. It is on calibration.

Craft Knowledge in Code

If traditional craft has been described as tacit knowledge accumulated through repeated manual practice, contemporary digital fabrication distributes that expertise across software environments and robotic systems. In computational workflows, decisions about geometry, density, and structural reinforcement are encoded before material is shaped. Skill does not disappear; it migrates upstream.

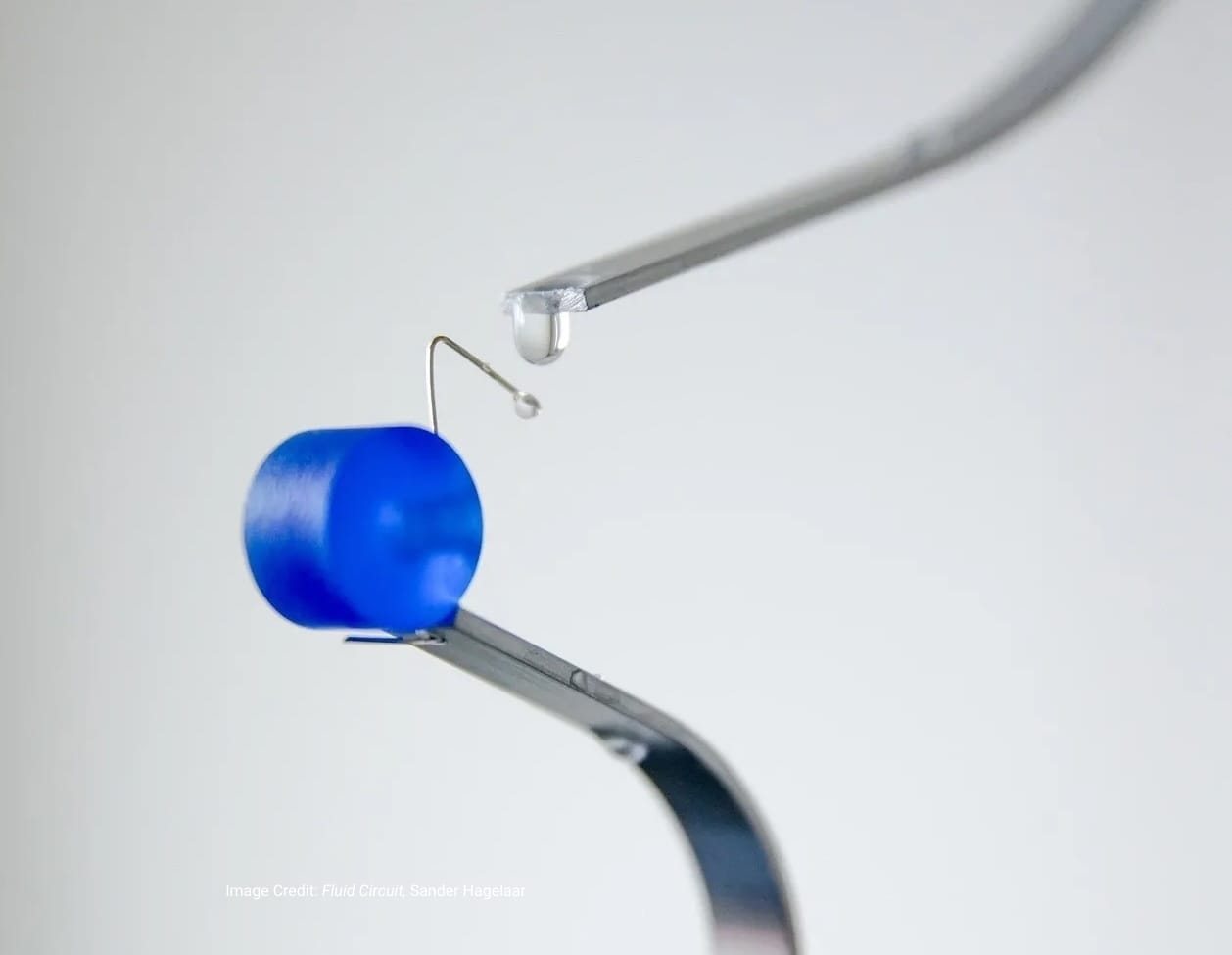

Dutch designer Joris Laarman has explored this migration for more than a decade. His collaboration with MX3D on the MX3D Bridge in Amsterdam used robotic wire-and-arc additive manufacturing (WAAM), a process that deposits molten metal through an electric arc. WAAM requires precise control of heat input, deposition rate, and structural stability. The bridge’s form emerged through generative modeling and structural analysis, then underwent empirical testing to ensure performance. Here, the designer configures systems rather than directly manipulating material. Robotic arms execute programmed instructions, but human operators define parameters, oversee calibration, and evaluate outcomes. Iteration remains central: simulation informs fabrication; fabrication feeds back into code.

This redistribution of expertise alters how error functions. In software-driven workflows, modeling inaccuracies can propagate through fabrication if left unchecked. As a result, prototyping, mock-ups, and sensor data remain essential. Digital precision does not eliminate craft judgment. It makes it procedural. Institutions have acknowledged this shift. The Victoria and Albert Museum (V&A) has collected and exhibited works incorporating generative design and digitally fabricated components, including projects by Laarman. By situating these works within decorative arts and design collections, the museum frames robotic fabrication as part of a longer history of material practice rather than as a break from it.

Why Post-Digital ≠ Anti-Digital

The “post” in post-digital does not mean after technology. Media theorists have used the term to describe a condition in which digital systems are normalized—embedded so deeply in production and culture that they become infrastructural. The question is no longer whether to use computational tools, but how they are configured and governed. Post-digital craft rejects two simplifications: the assumption that automation inherently produces better outcomes, and the idea that authenticity lies only in manual labor. Instead, it treats computation as material—something to shape, constrain, and interrogate.

This has implications beyond aesthetics. Research in distributed manufacturing and circular design suggests that localized, small-batch production—when combined with repairability and modularity—can reduce transportation and tooling waste under certain conditions. Hybrid workshops that combine CNC machining with hand-finishing or robotic printing with manual assembly introduce adaptability into systems often optimized for scale. These outcomes are contingent, not guaranteed. But they demonstrate that digital fabrication is not structurally tied to mass standardization.

Time also re-enters the equation. Sociological analyses of technological acceleration describe how modern systems compress production cycles. Yet hybrid digital–manual workflows still require machine calibration, simulation testing, and physical prototyping. These phases slow processes down—not as inefficiency, but as method. Iteration becomes a site of evaluation rather than delay.The rise of generative AI intensifies this terrain. As automated systems produce images, text, and product concepts at scale, debates around authorship and agency expand. Post-digital craft responds by embedding authorship within process design—within how systems are structured, constrained, and executed. Originality shifts from surface novelty to procedural specificity.

Post-digital craft is not a revival of pre-digital romanticism. It is a condition in which computation is fully integrated into materially grounded practice. Silicon and steel coexist. Script and surface inform one another. Machines do not replace judgment; they expose where judgment resides. The nostalgia narrative misses the point. What is emerging is not a retreat from technology, but a demand that technology remain accountable to material intelligence, human calibration, and sustained attention.