Across architecture, materials research, and experimental manufacturing, living materials have transitioned from lab-scale experiments to early-stage deployment. Mycelium composites, bacterial cellulose, and bio-reactive facades now function as test cases for a broader shift in how materials are conceived and managed. Their relevance for designers lies less in biological novelty than in the way these systems redistribute agency: when materials grow or adapt, questions of sustainability, authorship, and responsibility become operational rather than abstract.

In this context, sustainability can no longer be treated as a checklist of lower emissions or recycled inputs. Biodesign instead frames materials as active participants within ecological systems, prompting more fundamental questions. Who is responsible for a material’s lifecycle when it is partially alive? How should designers intervene—or deliberately refrain—from controlling biological processes? And what does authorship mean when outcomes are co-produced with living systems?

Biofabrication as a Design Method, Not a Material Substitute

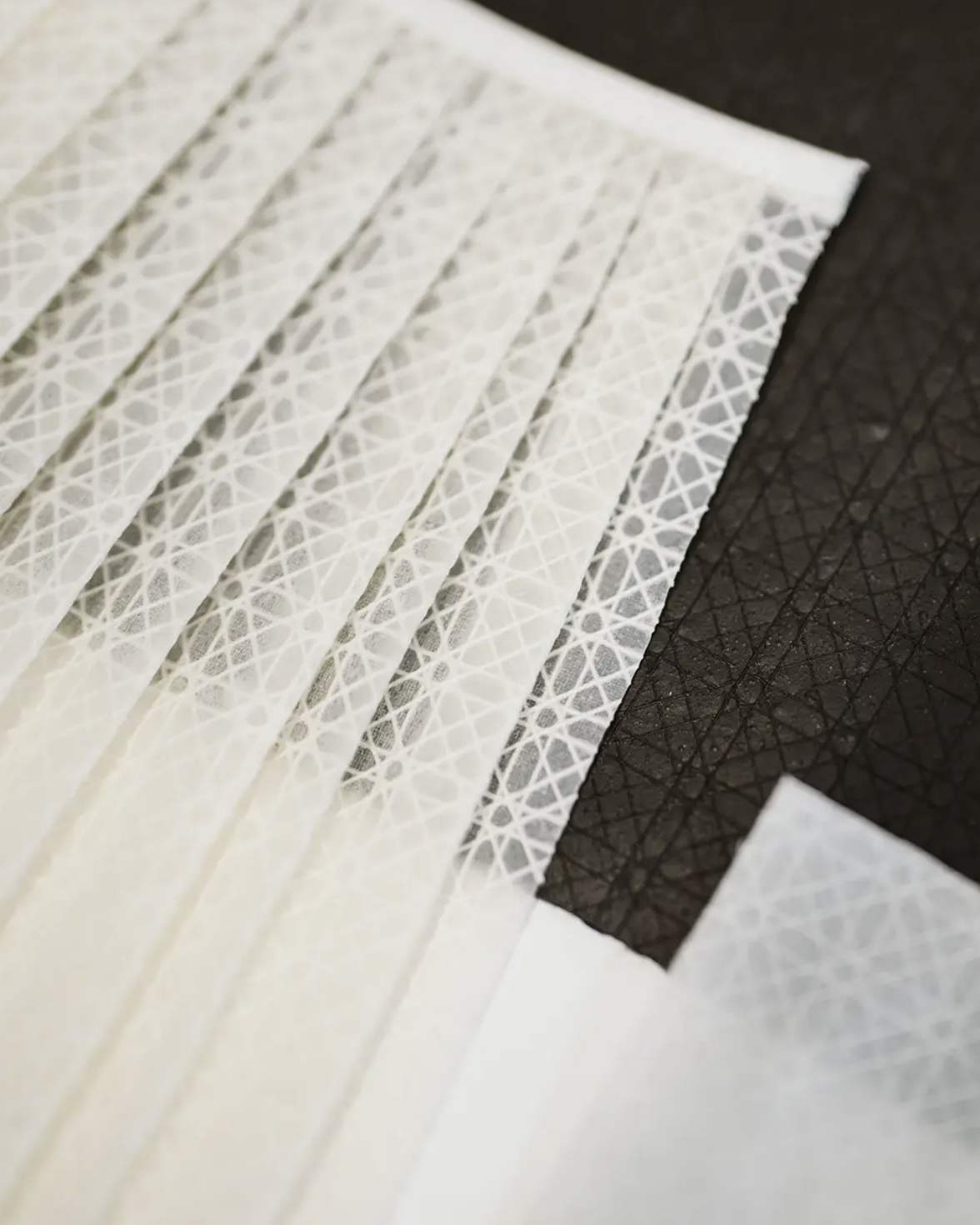

Biofabrication is often mischaracterized as a greener substitute for conventional manufacturing. In practice, it is better understood as a methodological shift. Techniques such as growing mycelium composites, cultivating bacterial cellulose, or producing microbial pigments replace extraction and machining with cultivation, environmental control, and care.

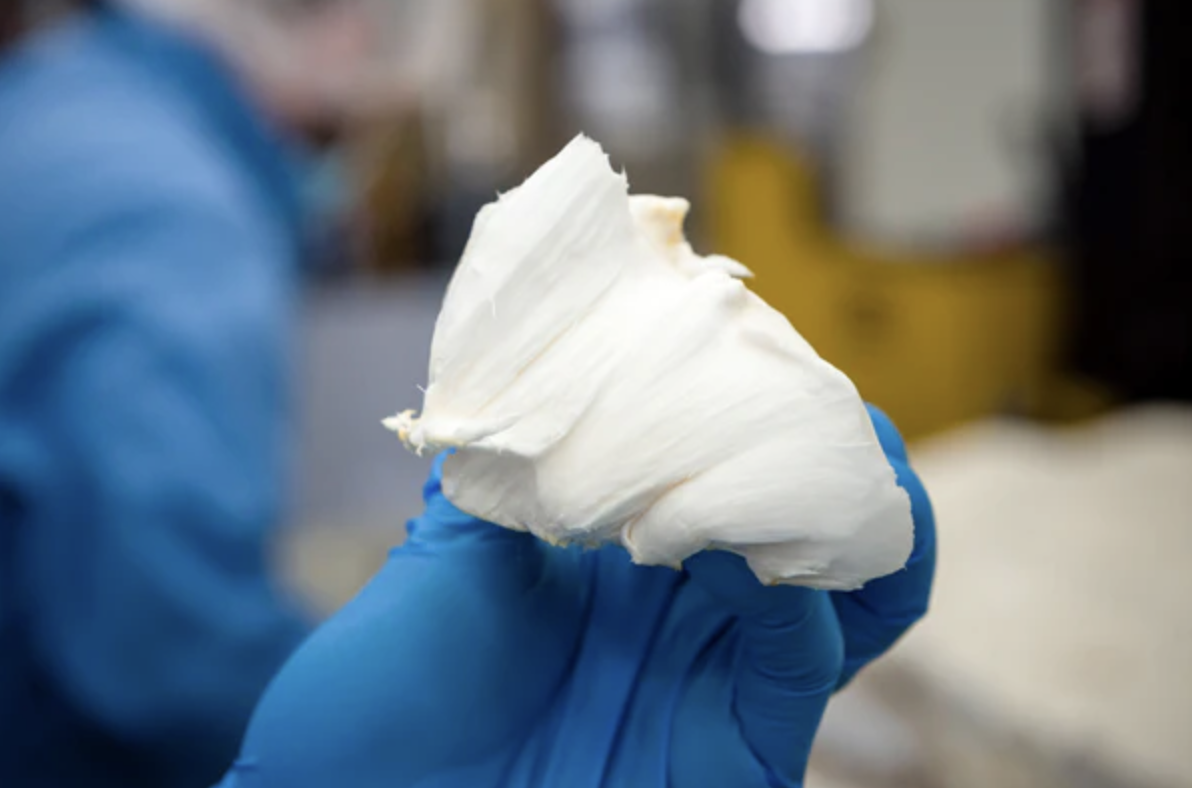

Companies like Ecovative have demonstrated that mycelium can be grown into structural packaging, insulation, and acoustic panels using agricultural waste as feedstock. While these materials are compostable and relatively low-energy to produce, their more consequential impact is conceptual: designers must account for growth rates, humidity, contamination risk, and material decay. Control becomes probabilistic rather than absolute.

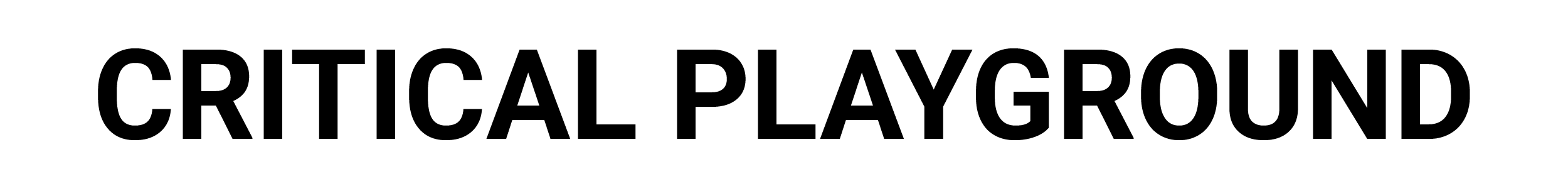

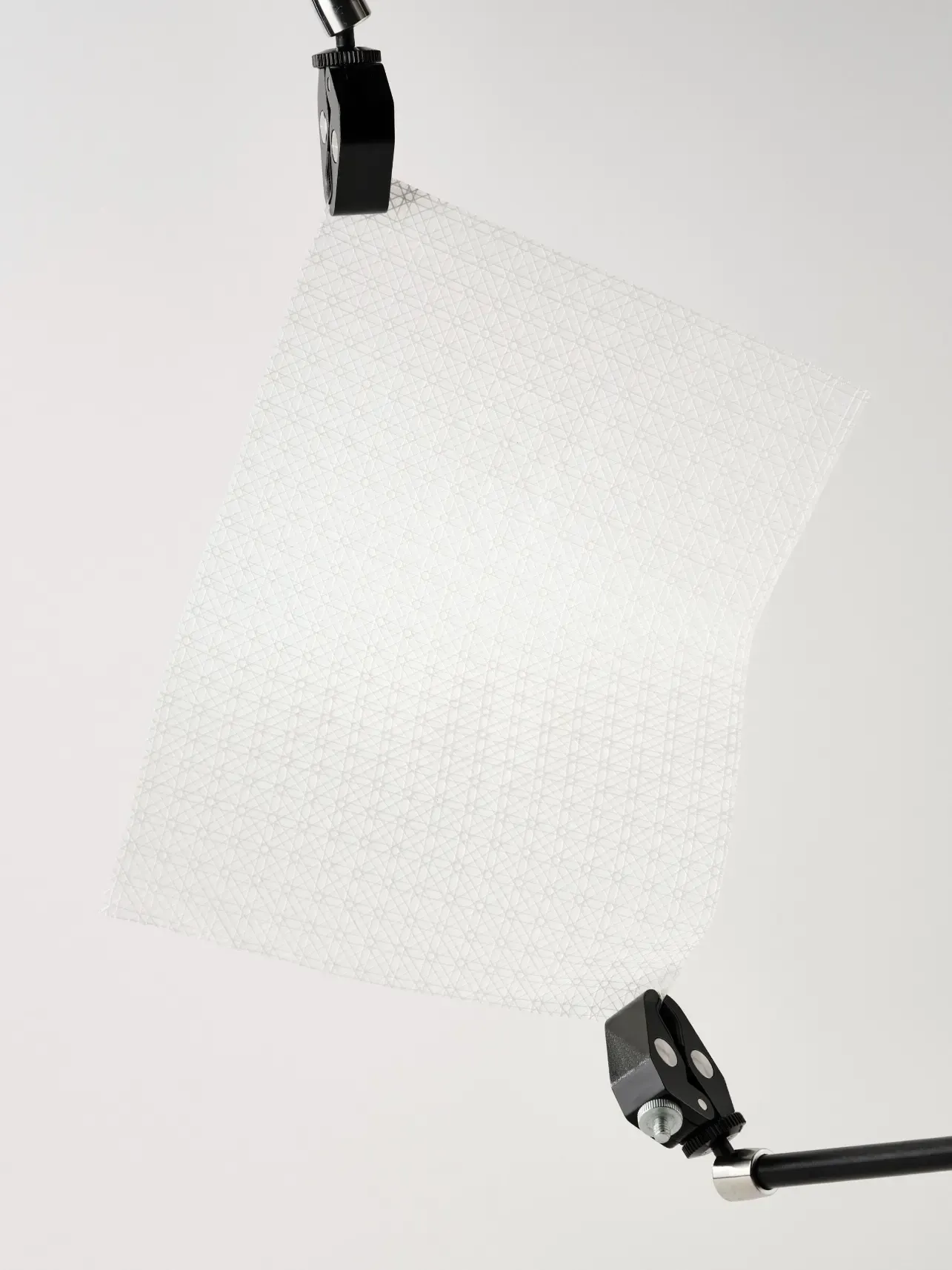

Similarly, studios such as Modern Synthesis treat bacterial cellulose not as a fixed output but as a responsive system shaped by tension, scaffolding, and environmental conditions. Design decisions occur upstream—through constraints, protocols, and feedback loops—rather than through post-processing alone. This challenges industrial assumptions about repeatability and standardization, foregrounding variability and responsiveness as design parameters.

Living Materials and the Redistribution of Authorship

When materials grow, authorship disperses. Designers define parameters, but outcomes emerge through biological processes that introduce variability and constraint. This redistribution of control is not a flaw but a defining characteristic of living materials, requiring designers to relinquish assumptions of total mastery in favor of collaboration with non-human systems. A chair grown from mycelium or a textile cultivated from microbes is not inert matter shaped solely by human intention. It is the product of metabolic labor performed by organisms. While these systems are not sentient, they operate according to their own logics, which can be disrupted by over-optimization or extractive timelines.

This reframing aligns with broader shifts in systems thinking and post-human design theory. Authorship becomes infrastructural: the designer’s role is to set conditions, define thresholds, and anticipate downstream effects. Responsibility, in turn, extends beyond aesthetics to include care, maintenance, and end-of-life pathways.

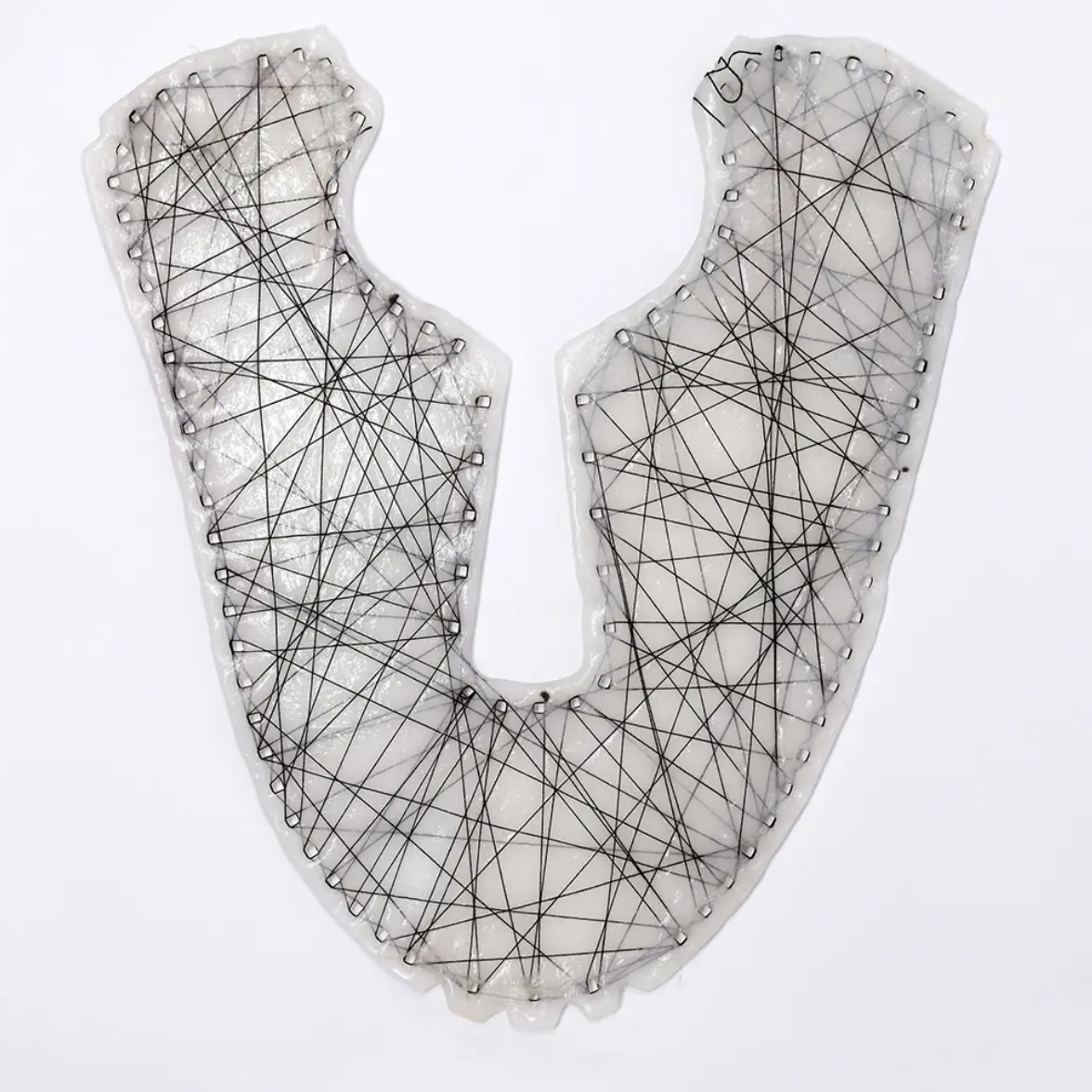

From Biofabrication to Bio-Integrated Energy Systems

Living materials are not limited to objects and surfaces. They are increasingly embedded in architectural and energy infrastructures. One of the most cited examples is the algae-powered facade developed for the BIQ House in Hamburg, which integrates bioreactor panels into a building envelope to generate biomass and thermal energy. Developed by Arup in collaboration with SSC Strategic Science Consult, the SolarLeaf system demonstrates how biological processes can be integrated into urban energy systems. Algae growth within the facade responds to sunlight, producing heat and biomass while also acting as dynamic shading.

Crucially, this is not a decorative application of “green” aesthetics. It is a systems-level intervention that links material behavior, energy production, and environmental performance. Yet it also exposes ethical tensions: bio-integrated systems require ongoing monitoring, nutrient inputs, and technical oversight. Sustainability here is not passive; it is operational and labor-intensive.

Ethics Beyond Sustainability Metrics

The ethics of biodesign cannot be reduced to carbon accounting or biodegradability claims. While many living materials offer environmental advantages, their true ethical challenge lies in how they reconfigure responsibility. Designers must consider not only how materials are made, but how they are maintained, governed, and disposed of.

There is also a risk of bio-solutionism—using living materials as symbolic fixes for systemic environmental problems. A mycelium wall panel does little if embedded in a supply chain built on overproduction and short-term use. Ethical biodesign requires alignment between material innovation and broader economic and cultural shifts toward maintenance, repair, and sufficiency. Living materials demand longer timelines, interdisciplinary collaboration, and transparency about uncertainty. They also invite designers to think politically: about who bears the cost of care, who benefits from regenerative systems, and how biological labor is valued within capitalist frameworks.

Living and regenerative materials are reshaping design not by offering a single solution to sustainability, but by forcing a reconsideration of how design intervenes in the world. As biofabrication and bio-integrated systems move from research to deployment, the central question is no longer whether these materials work. It is whether designers are willing to accept the ethical responsibilities that come with designing alongside life.