In 1969, Charlotte Moorman strapped two television sets to her chest and played the cello. The piece, TV Bra for Living Sculpture, was a collaboration with Nam June Paik. It wasn’t a product prototype. It was performance art. But it might also be the earliest example of wearable media—decades before smart glasses or fitness trackers made it to market.

That kind of overlap—between speculative design and emerging tech—didn’t stop with a TV corset. In fact, much of what we now associate with wearable technology has roots not in engineering labs or Silicon Valley startups, but in performance art, critical fashion, and avant-garde design. While corporations were still building calculator watches and pedometers, artists were already asking the harder questions: What happens when the body becomes a screen? A sensor? A node?

This is the evolution of wearable technology seen through a different lens—one shaped by aesthetics, critique, and experimentation.

Performance as Prototype

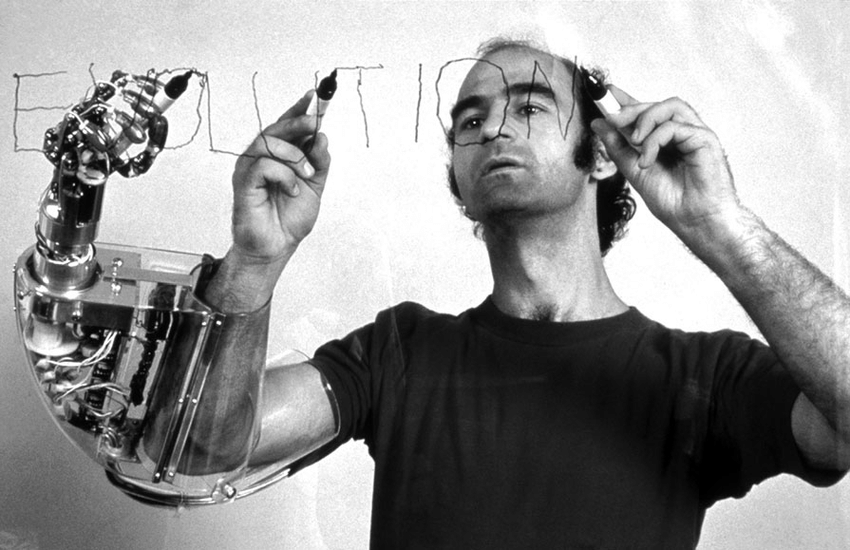

Before the quantified self, there was the augmented body. In the 1980s, Australian performance artist Stelarc began incorporating robotics and prosthetics into his live performances. Third Hand (1981–1998) featured a mechanical arm wired directly to his nervous system. The goal wasn’t utility—it was provocation. Stelarc wasn’t trying to streamline productivity; he was questioning human centrality in a world increasingly driven by machines.

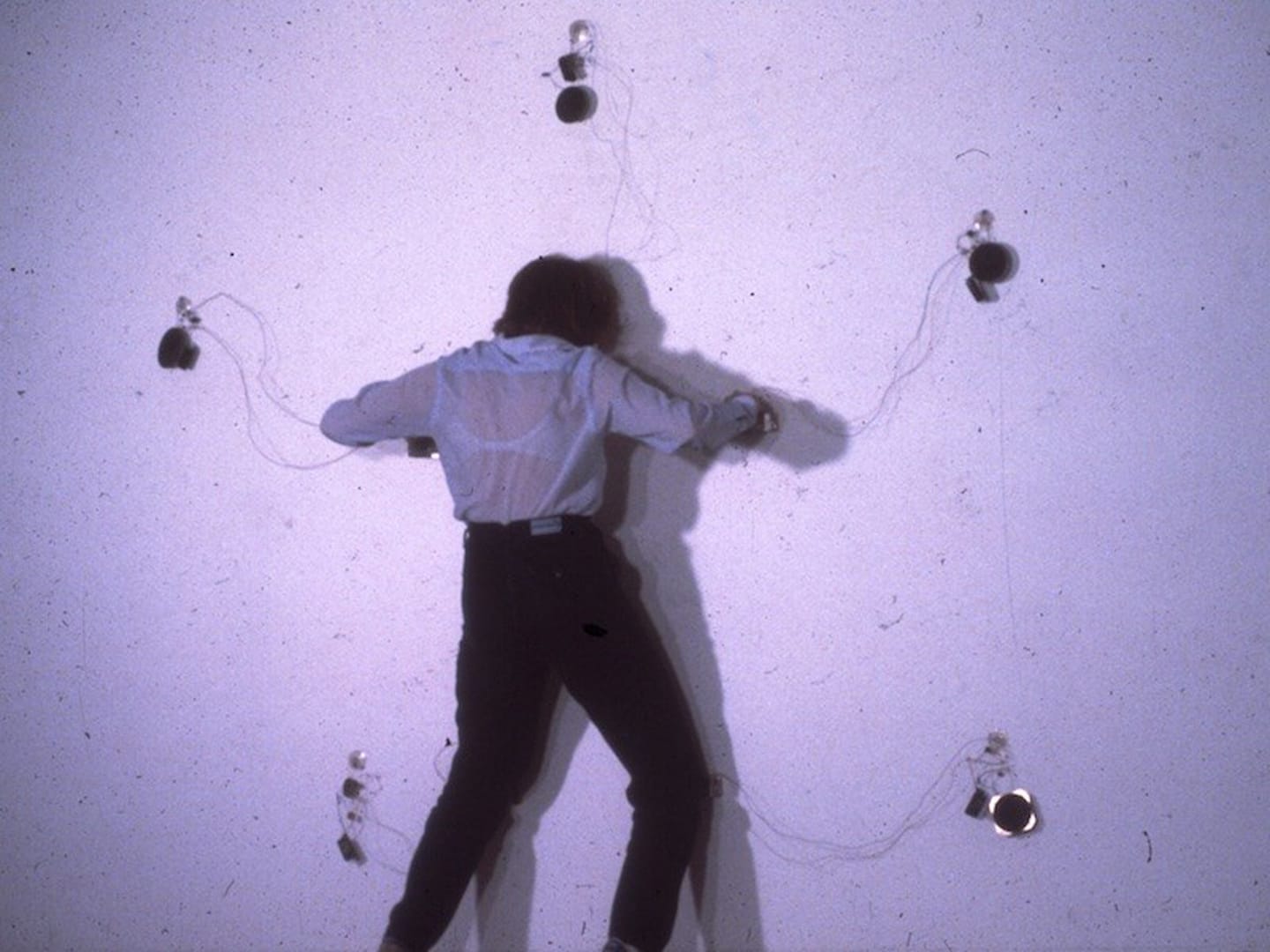

Meanwhile, Canadian artist Diana Burgoyne built analog circuits designed to be worn on the body. Her works buzzed, blinked, or responded to the wearer’s movements. They weren’t sleek or optimized. That was the point. They made the tech visible—intimate, clunky, and alive.

Together, these projects shifted the wearable narrative from convenience to confrontation. They didn’t ask what technology could do for the body. They asked what it would do to it.

Fashion Gets Functional—and Political

By the late 1990s, designers were embedding sensors, actuators, and circuitry into garments—not to launch new product lines, but to test the edges of behavior and perception. Hussein Chalayan’s Remote Control Dress (2000) was one of the first garments to morph in real time via remote signal. The runway model stood still. The dress reconfigured itself. Chalayan wasn’t selling hardware; he was demonstrating how technology could reshape identity, space, and intimacy.

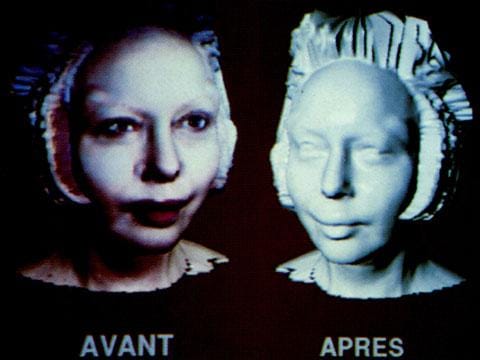

At MIT’s Media Lab, researchers like Rosalind Picard were working on affective computing—building garments that could detect and respond to emotion. These were early versions of what would become biometric sensing in consumer devices, but the research was rooted in psychology and ethics, not calorie tracking. At the same time, Orlan’s surgical performances, including Reincarnation of Saint-Orlan (1990–1993), reframed the human face as a modifiable interface. Her work merged body modification and wearable prosthetics into one continuous act of authorship, confronting the idea that wearable tech had to be invisible or seamless. Sometimes augmentation is messy, surgical, and impossible to ignore.

From Art to Infrastructure

As commercial wearables emerged in the 2010s, experimental designers kept pushing. Their projects didn't just mirror tech trends—they challenged them. Take Anouk Wipprecht’s Spider Dress (2015), which responds to proximity using embedded sensors and robotic limbs. If someone gets too close, the limbs lash out defensively. It’s part fashion, part exoskeleton, and part commentary on gendered social space. Wearable tech, this project suggests, doesn’t always have to be polite.

On the material innovation front, Pauline van Dongen’s Solar Shirt (2014) wove flexible photovoltaics into the fabric itself, turning the garment into a mobile power source. Her work aligned wearable tech with sustainability, years before the industry caught on. These weren’t just garments with gadgets. They were systems—each embedded with social, political, and environmental critiques.

Designing for Uncertainty

Today, wearable tech is largely about metrics. Steps, sleep, blood oxygen. But artists are still building alternative models—ones that prioritize ambiguity over optimization. Behnaz Farahi’s Returning the Gaze (2021) uses facial recognition and motion to track who’s watching the wearer and respond kinetically. It reverses the surveillance dynamic and interrogates power.

Ying Gao’s Incertitudes (2021) features a voice-reactive dress that animates in response to tone and intensity, not words. It doesn’t decode speech—it listens to feeling. Her work prioritizes sensitivity and slowness over clarity and efficiency.

Even humor has its place. Kate Hartman’s Talk to Yourself Hat (2009) is exactly what it sounds like—a wearable that turns introspection into interface. It’s absurd and deadpan, and it raises serious questions about the future of mental health devices now entering the market.

Reclaiming the Narrative

The history of wearable technology isn’t just about consumer adoption curves or microprocessor breakthroughs. It’s also about speculation, critique, and performance. For every engineering milestone, there was an artist somewhere asking the questions the market wasn’t ready to face: Who controls the data? What happens to autonomy? Is seamless always better? The legacy of experimental art and design reminds us that wearable tech isn’t just something we strap on. It’s something that shapes our behavior, reveals our values, and increasingly mediates how we relate to others.

If we want smarter wearables, we might need to start listening to the people who were hacking the body before it was cool.