When it comes to urban planning and environmental resilience, hyperlocal data is the new gold. Forget abstract simulations or satellite models; the most actionable intelligence often comes from the ground up—captured by citizens, embedded sensors, and participatory tools that map what top-down systems miss. Increasingly, designers are stepping into this space, transforming grassroots datasets into tangible interventions that rewire infrastructure, rethink health systems, and reshape civic engagement. This design-led approach to data collection and application doesn’t just visualize the invisible. It rewrites who gets to produce knowledge—and how that knowledge can be used.

Sensing Pollution, Sculpting Air

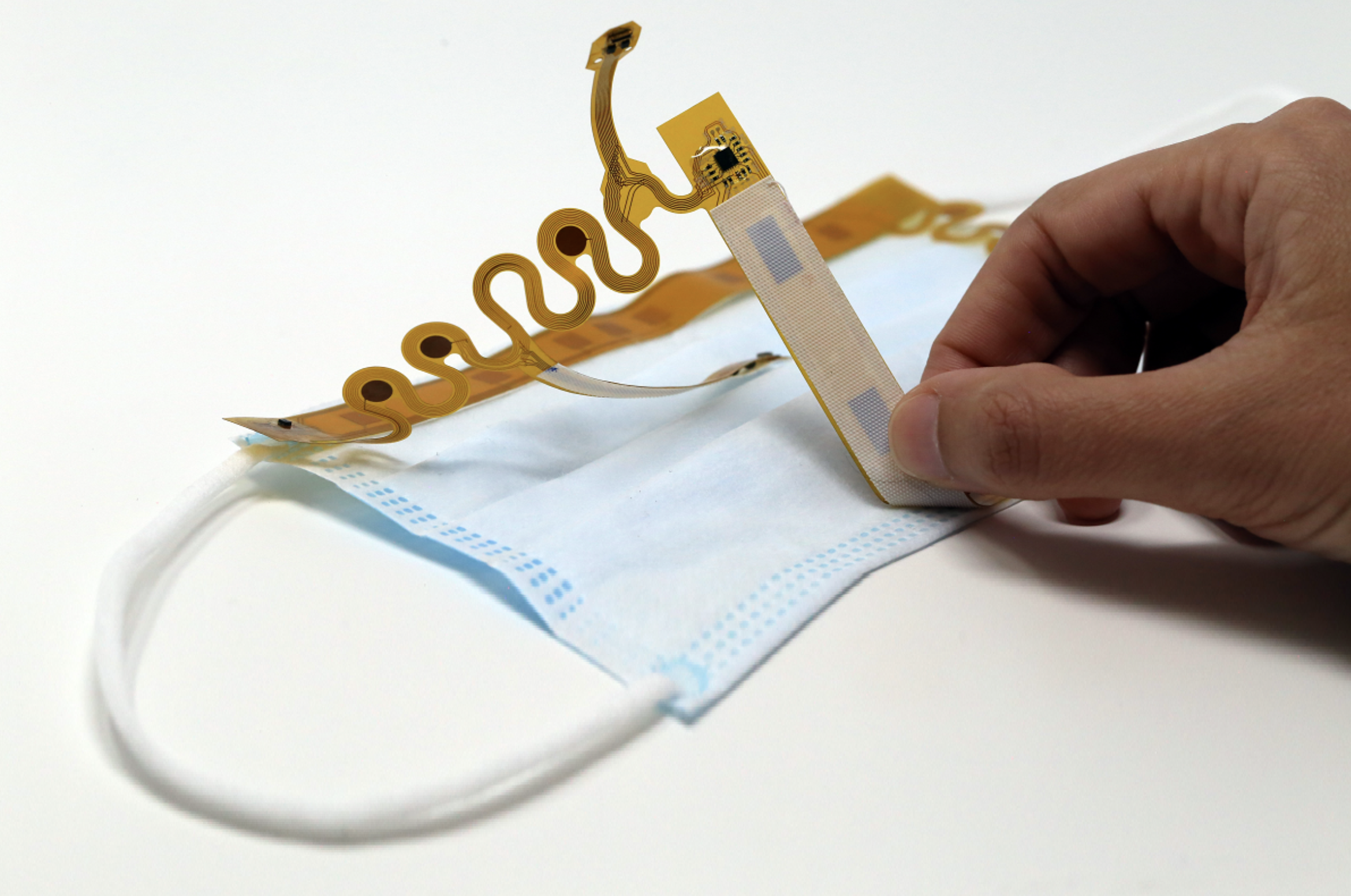

In 2018, artist and designer Kasia Molga created Human Sensor, a series of wearable devices that reacted to air pollution in real time by lighting up when exposed to high levels of particulate matter.

Image Credit: Human Sensor, Studio Molga in collaboration with Invisible Dust

Commissioned by Invisible Dust, the garments were worn in Manchester and London, where they visualized the body's exposure to toxic air as the wearers moved through the city. The premise was simple but powerful: turn atmospheric data into bodily feedback. Human Sensor didn’t just raise awareness; it turned wearers into living monitors—citizen sensors in motion.

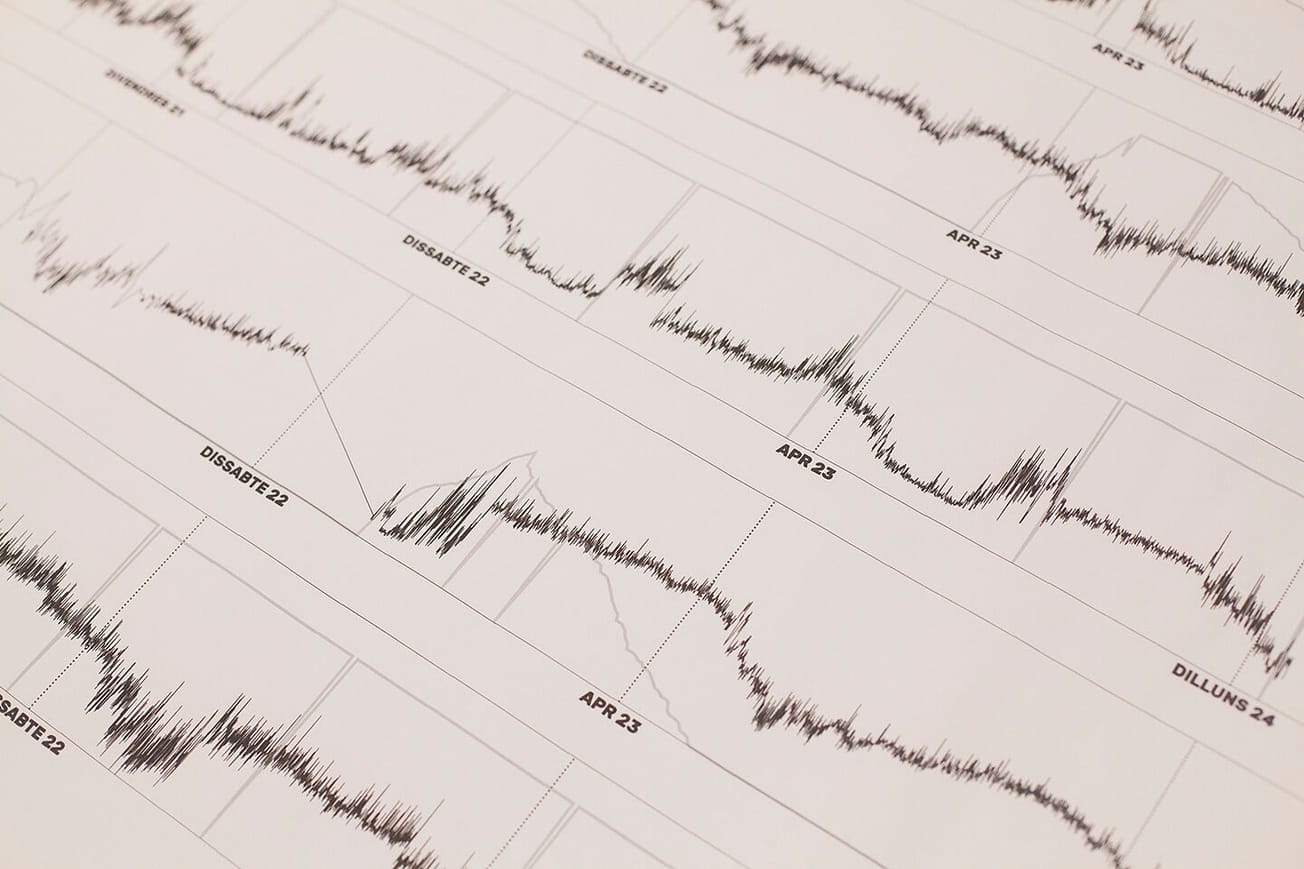

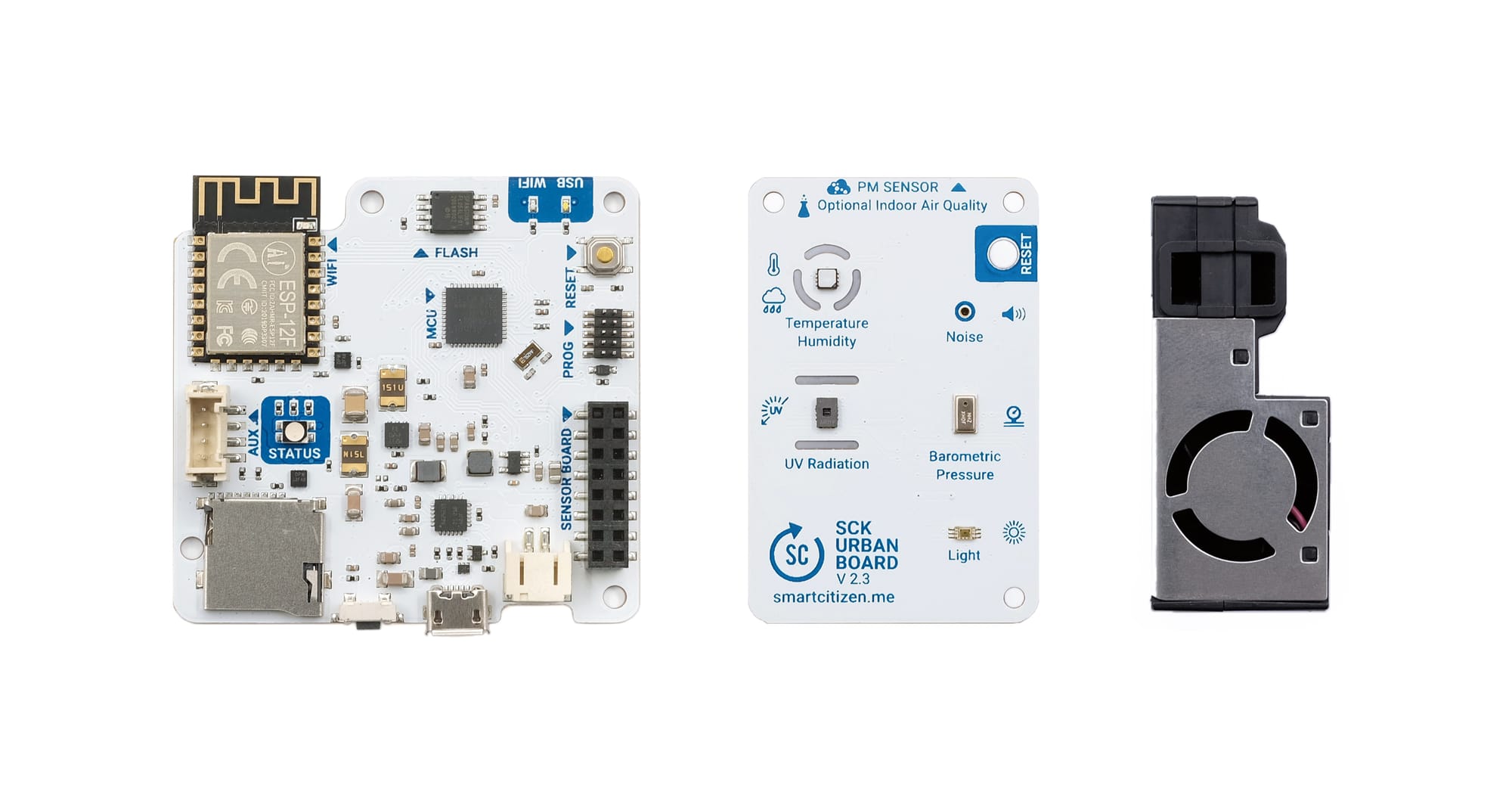

Molga isn’t alone in this space. Smart Citizen, developed by Fab Lab Barcelona at the Institute for Advanced Architecture of Catalonia (IAAC), provides an open-source platform that enables people to monitor environmental conditions—such as air quality, noise levels, temperature, and humidity—through modular sensor kits. The project, which began in 2012, has grown into a global network that connects citizen-sourced data with open platforms and design-led research. Deployed in cities like Barcelona, Oslo, and Amsterdam, Smart Citizen integrates DIY hardware with public infrastructure, offering real-time data dashboards that feed into everything from classroom curricula to urban mobility policy.

GIS as Civic Infrastructure

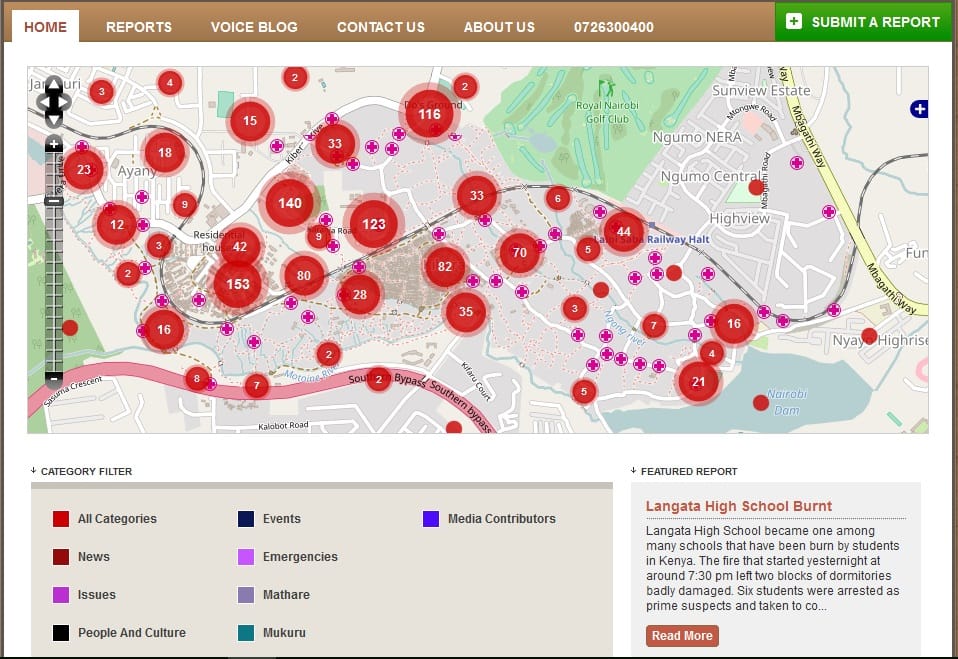

Data-centric design also intersects with spatial justice through participatory mapping. Projects like Map Kibera in Nairobi have shown how community-driven cartography can fill in critical gaps left by official datasets. Initially launched in 2009, the initiative equipped young residents with GPS-enabled phones and trained them in open-source GIS tools to map roads, schools, clinics, and water points in what had previously been considered a “blank spot” on official maps.

The results did more than increase visibility—they enabled planning for improved sanitation and emergency response, and provided NGOs and civic agencies with data they could actually use. The project has since expanded into GroundTruth Initiative, advocating for participatory data systems as infrastructure in themselves.

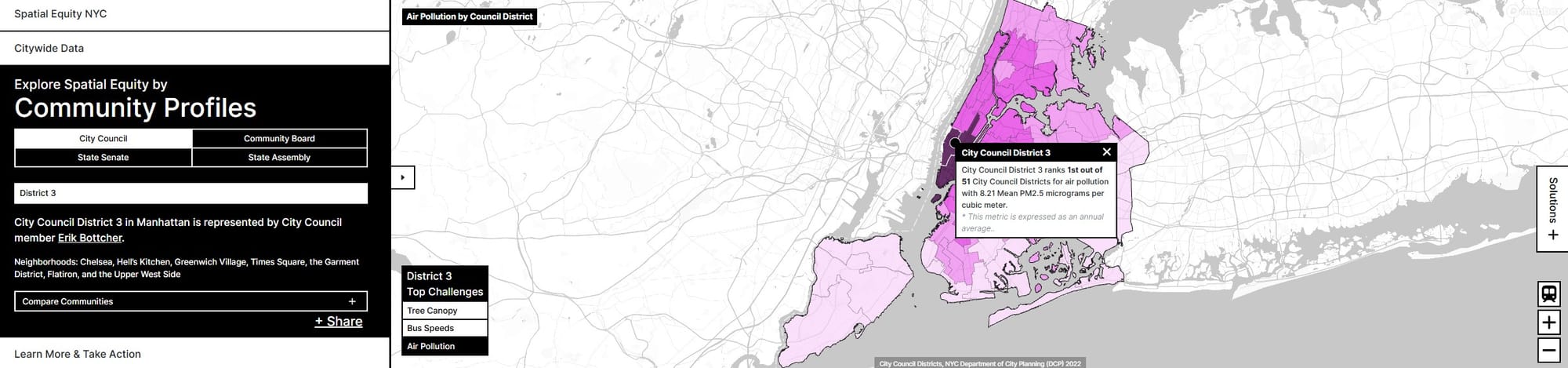

Meanwhile, in the U.S., the American Planning Association and designers at MIT’s Civic Data Design Lab, led by Sarah Williams, have turned spatial analytics and design into civic tools. A notable recent example is Spatial Equity NYC, an interactive online platform that maps neighborhood-level data—traffic volumes, air quality, park access, and demographic information—to highlight patterns of environmental and infrastructural inequality across New York City. Using municipal data and open APIs, the tool enables planners, community groups, and residents to explore how pollution burdens correlate with urban geography and social stratification. It exemplifies the lab’s “Data | Action” approach: deploy data in public-facing platforms that support evidence-based advocacy, city planning, and equitable design interventions.

When Wearables Go Epidemic

During the COVID-19 pandemic, researchers at MIT, led by materials scientist Canan Dağdeviren, developed cMaSK (Conformable Sensory Facemask), a thin-film wearable sensor system embedded into standard face masks. Published in Nature Electronics in 2022, the device continuously monitors key respiratory metrics—including breathing patterns, coughing frequency, temperature, and humidity—without requiring bulky hardware or user intervention. Designed for everyday use in schools, public transit, or clinics, cMaSK offers real-time physiological data that can inform both personal health decisions and broader epidemiological models. It represents a new frontier in responsive wearables: one that blends human-centered design with precision biomedical sensing to bridge individual experience and public health infrastructure.

Design Interventions with Feedback Loops

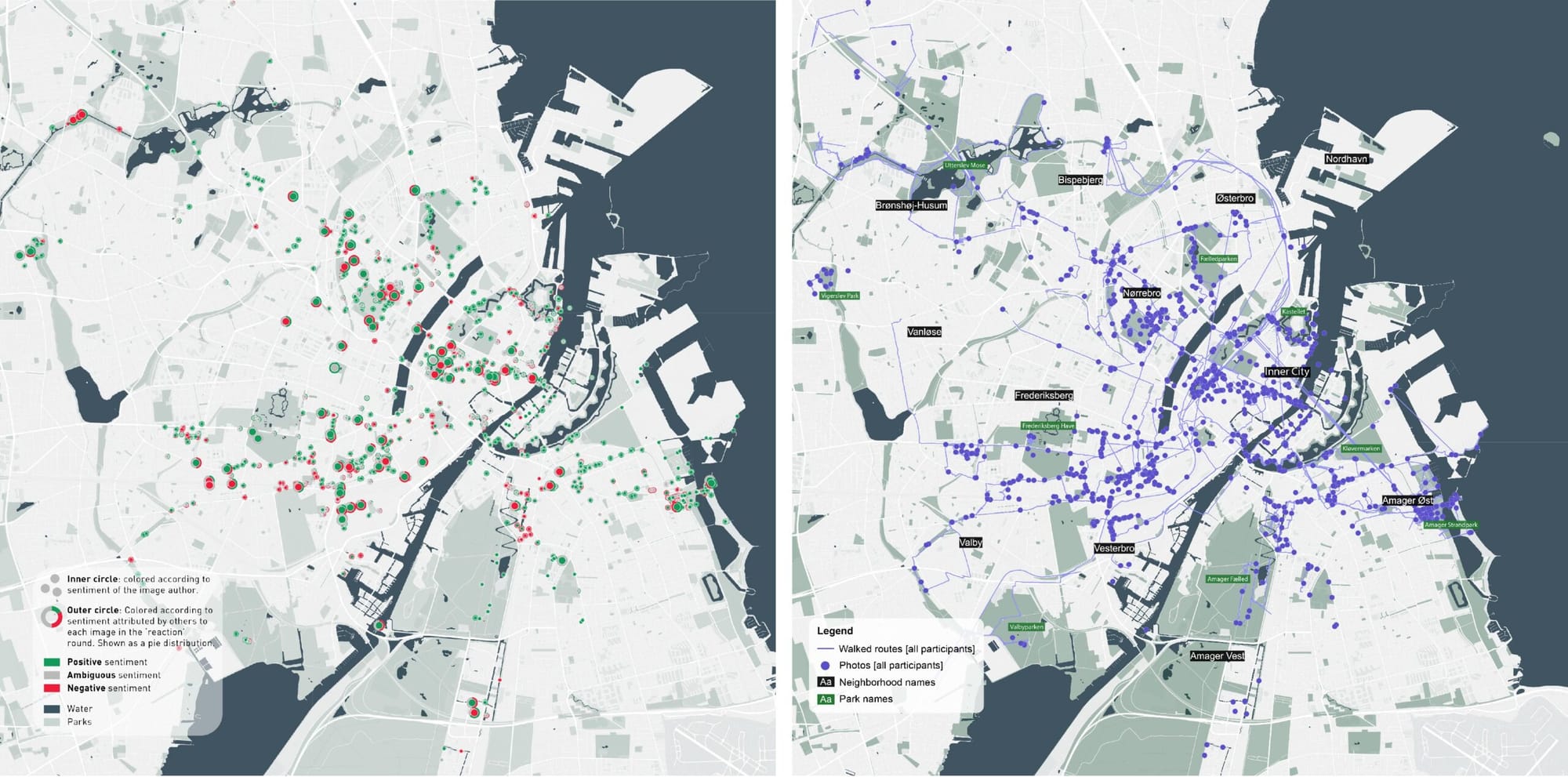

Designers aren’t just collecting data—they’re responding to it. The Urban Belonging project by Gehl, a global urban design consultancy, uses ethnographic and sensory data gathered from residents to shape inclusive public space interventions. Conducted across cities like Copenhagen, San Francisco, and Porto Alegre, the project uses surveys, walkalongs, and participatory mapping to document how people feel in urban environments—data that gets directly fed into design recommendations.

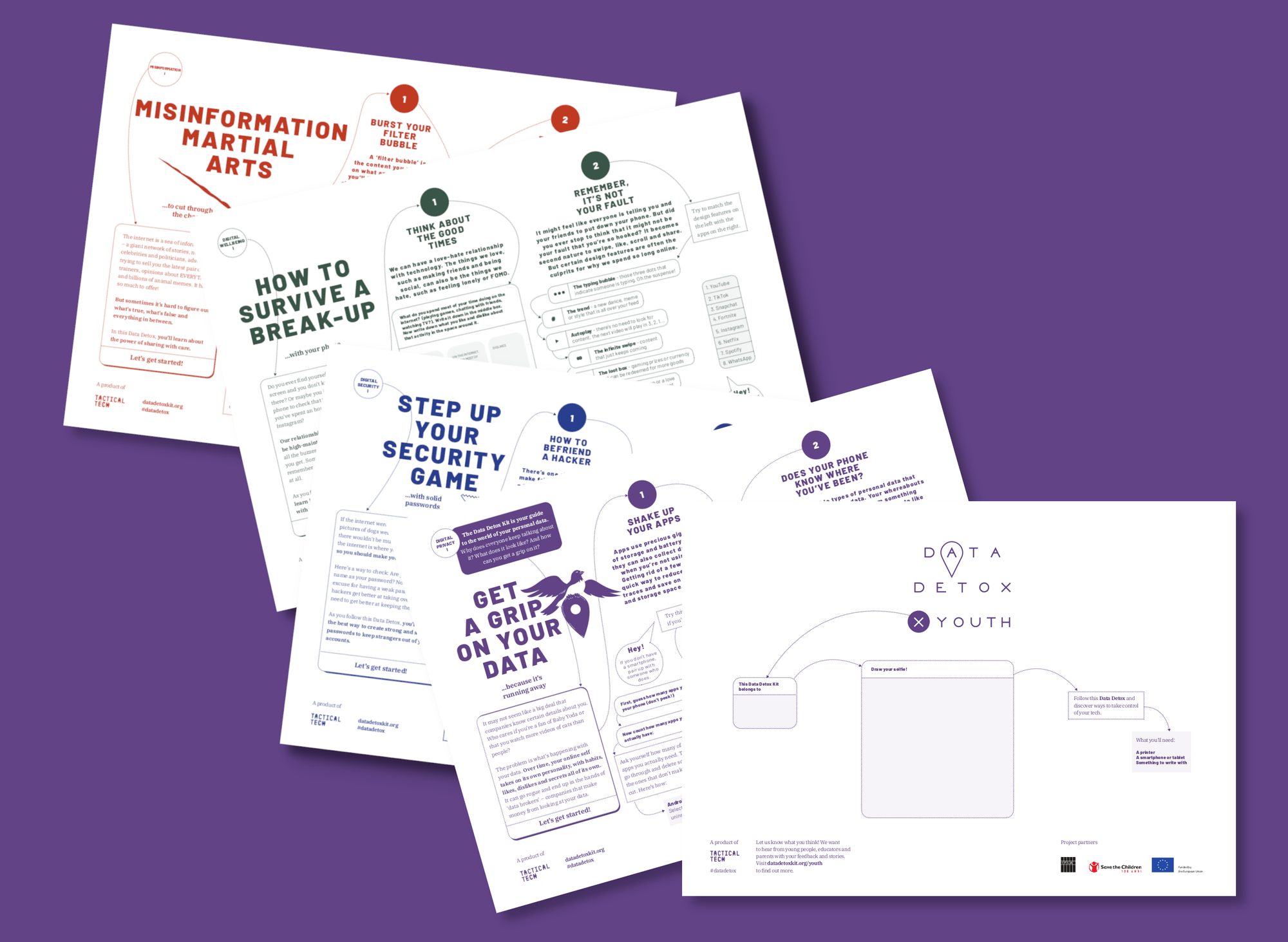

Berlin-based Tactical Tech offers another compelling model. Their Glass Room exhibitions and Data Detox Kit equip communities with tools to understand and critically engage with data-driven systems. While not spatial designers per se, their public interventions reframe how design can support data literacy, privacy, and empowerment—particularly in environments saturated by opaque technologies. By translating complex technical systems into accessible, experiential learning, Tactical Tech builds a civic data fluency that complements more traditional infrastructure interventions.

These feedback loops between data, design, and public use are crucial. They ensure that interventions are not just speculative but grounded in lived experience and local knowledge.

The Politics of Participation

With the rise of smart cities and urban IoT, it’s tempting to conflate data-rich environments with democratic ones. But access to data and the ability to act on it are not equally distributed. That’s why the role of designers as mediators—translating raw information into accessible tools and equitable systems—is more important than ever. Design Justice Network, for example, emphasizes co-design principles to ensure marginalized voices shape the tools being built. Similarly, the Open Data Institute in the UK advocates for ethical frameworks that prioritize data sovereignty and community control.

The challenge going forward is less about technological capacity and more about infrastructure, trust, and consent. Who owns the data? Who gets to interpret it? Who benefits from its application? As sensors become cheaper, GPS more ubiquitous, and machine learning more embedded in everyday tools, the field is open. But as these case studies make clear, the most impactful design doesn’t just collect data—it designs with it, and for the people who generated it.