In 2017, a black Cadillac cruised across the American Southwest with a GPS, a camera, and a laptop in the passenger seat. As the miles rolled by, a neural network spat out sentences, line by line, from behind the dashboard. Artist and creative technologist Ross Goodwin called it 1 the Road—an AI-authored novel in motion. The experiment didn’t just question what a story is. It asked who—or what—gets to write it.

Generative storytelling isn’t just a new artistic technique. It’s an evolving design language—one that recasts authorship, agency, and originality through the lens of automation. In this world, the author is less a narrator and more a system operator. And the narrative is not a fixed plot, but a living protocol: shaped by data, prompted by intention, and often rewritten midstream. As artists and designers push further into AI-generated narrative art, they aren’t just creating with machines—they’re exposing the assumptions behind them. Who decides what counts as authorship in a feedback loop of models and inputs? How does originality survive in an environment trained on everything that came before?

The answers are messy—and increasingly urgent.

Systems That Write Back

Artist and coder Lauren Lee McCarthy has been working on that question for years. In her 2019 project SOMEONE, she posed as a smart-home assistant for real people—watching, listening, responding in real time to their daily lives. But unlike Alexa or Siri, this system had no backend automation. It was McCarthy herself behind the scenes, pretending to be the AI. The work collapsed the boundary between interface and intention, automation and intimacy. It wasn’t just about technology—it was about trust, authorship, and who controls the narrative of daily life.

In McCarthy’s hands, generative systems become mirrors—tools that reflect human desires back through a machine-shaped lens. The performance isn’t a simulation of agency. It’s a critique of how easily we give it away. Nora Al-Badri explores similar tensions through a different lens: cultural ownership. In projects like The Other Nefertiti and Babylonian Vision, she uses AI to generate speculative reconstructions of artifacts housed in Western museums—objects often looted through colonial histories.

By training models on digitized scans of these artifacts, she creates counter-archives: synthetic originals. Her work reframes generative art as an act of reclamation. It's not about novelty—it’s about narrative sovereignty.

Where McCarthy manipulates the interface and Al-Badri interrogates the archive, K Allado-McDowell goes deep inside the neural loop. In their hybrid works Pharmako-AI and Amor Cringe, Allado-McDowell collaborates with GPT-3 to generate autofictional texts that blend human and machine voice. The outputs are fragmented, recursive, and speculative. There is no singular “I,” just a chorus of probabilities. The result isn’t a story about AI. It’s a story as AI. “I felt I had to write this book with GPT-3 because I could no longer think alone,” Allado-McDowell writes. The collaboration becomes a form of surrender—and a provocation. Who is the author when no one can trace the origin of a sentence?

Misuse, Mutation, and the Myth of Coherence

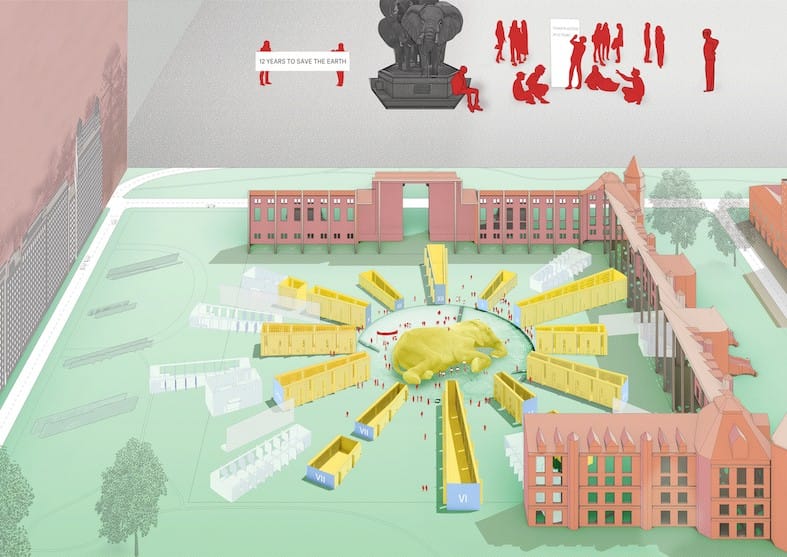

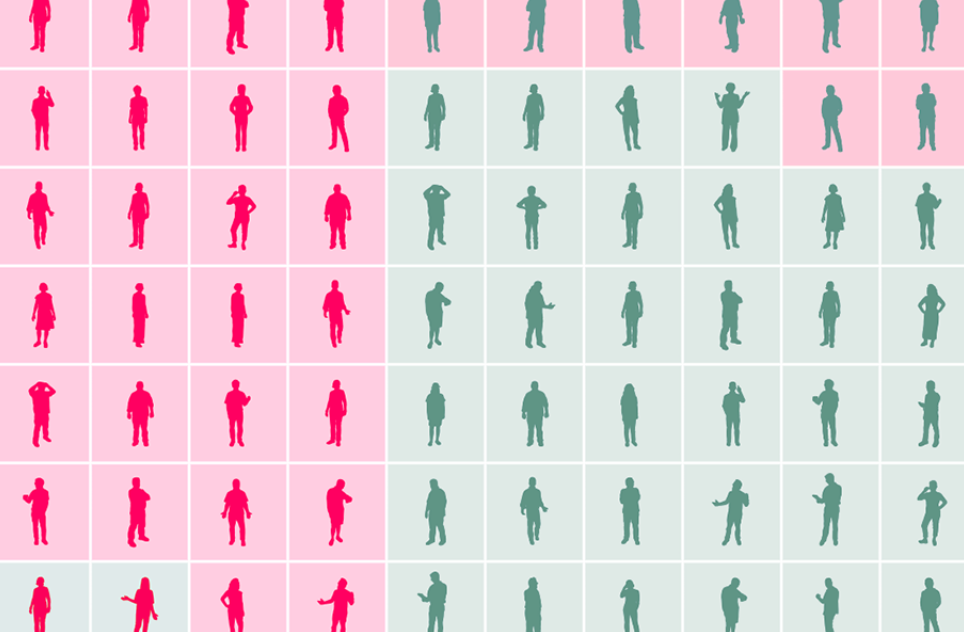

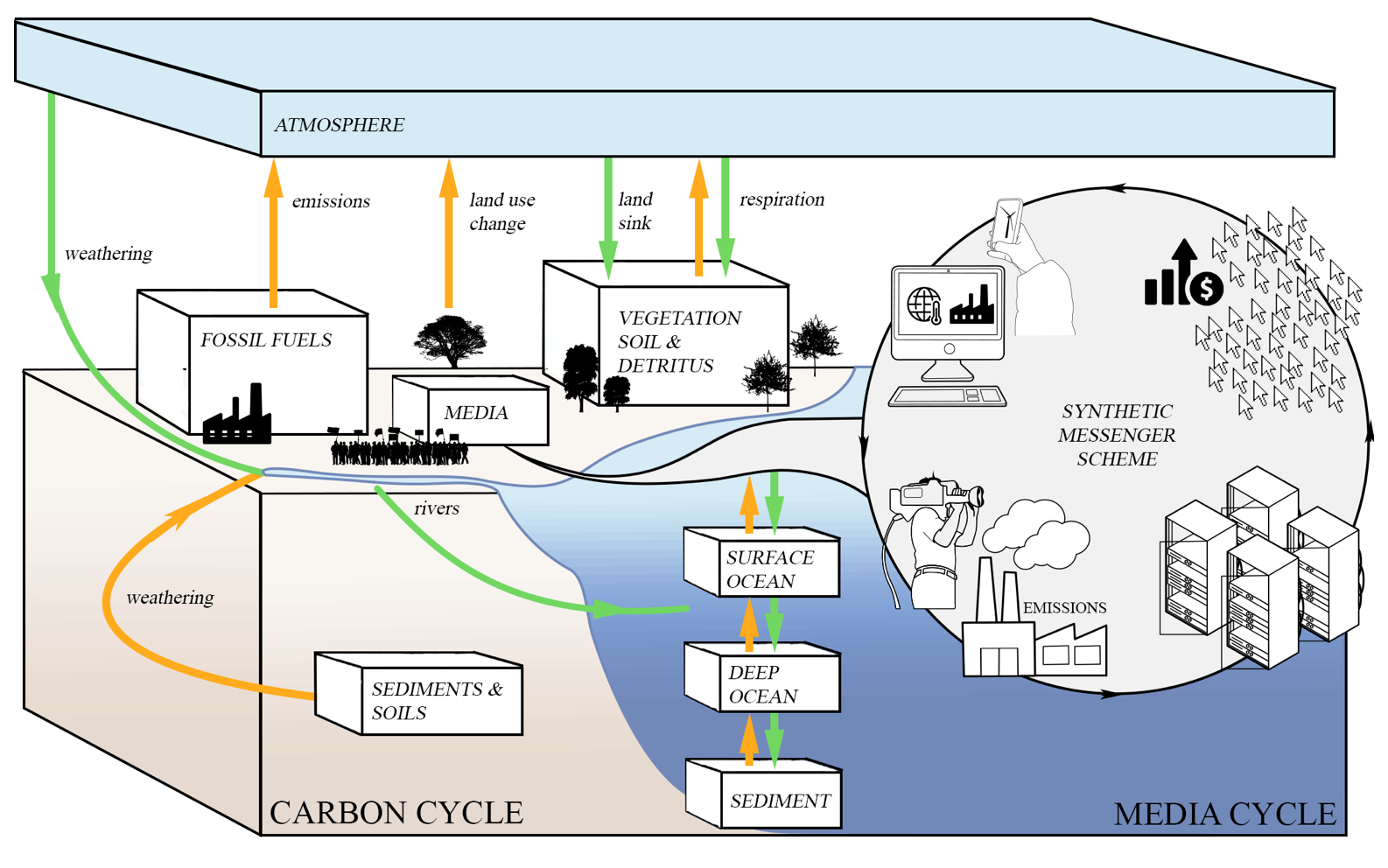

In the world of Sam Lavigne and Tega Brain, narrative doesn’t start with characters or plots—it starts with data. Their 2021 project Synthetic Messenger used bots to flood advertising networks with synthetic clicks on climate news, attempting to trick content algorithms into thinking public interest was spiking. The story wasn’t in the media coverage—it was in the infrastructure of perception.

Their work reframes storytelling as systems manipulation. It’s not about the message—it’s about the mechanism that determines who hears it, and when.

Ross Goodwin, who generated Sunspring (a sci-fi short film written entirely by an LSTM neural net), leans into the absurd. The script’s lines are surreal and incoherent—until actors perform them straight. Then, oddly, meaning emerges. Not from intention, but from interpretation. The audience completes the circuit. This isn’t machine authorship—it’s machine ambiguity, channeled through human delivery.

Allison Parrish pushes this further into poetic terrain. Her generative poetry tools—like those behind Articulations—aren’t interested in simulating human writing. They celebrate misfire, misalignment, and mutation. Words are shuffled, patterns repeated until language becomes abstract texture. Parrish doesn’t use AI to mimic authorship—she uses it to break it open. Her work suggests that originality doesn’t come from invention, but from friction. The machine resists coherence, and from that resistance, new structures emerge.

Rethinking Narrative as Infrastructure

What ties these artists together isn’t genre or discipline—it’s refusal. Refusal to accept AI as a neutral collaborator. Refusal to see authorship as a solitary act. Refusal to treat originality as untouched terrain.

In their hands, generative narrative becomes a site of resistance: to platform capitalism, to colonial epistemologies, to creative myths shaped by industrial systems. These works don’t just illustrate AI—they expose its politics. They force us to ask who benefits from automated authorship, and who gets left out of the story. As generative tools move from fringe to default in publishing, film, and design, these questions become cultural—existential, even. If anyone can generate a story with a prompt, what becomes of the author? If the model is trained on millions of voices, who speaks when it speaks?

Generative storytelling doesn’t kill the author. It multiplies them. And it challenges us to build new frameworks—legal, artistic, ethical—to handle that proliferation.