Design has long borrowed from biology, but the current shift goes further than biomimicry or nature-inspired form. A growing movement toward regenerative intelligence positions living systems as collaborators in design—systems that respond, adapt, and evolve rather than remain fixed. The focus is no longer on extracting efficiency from ecological forms; it is on working with ecological processes to build resilience, feedback-driven infrastructures, and multispecies forms of cohabitation.

Across architecture, materials research, and landscape design, a set of practitioners is reframing intelligence itself as ecological: distributed, cyclical, and interdependent. Their work suggests a structural transition in design culture, one that moves away from optimization as a dominant paradigm and toward strategies that regenerate the conditions that make environments livable.

From Optimization to Ecological Feedback

Most design systems still operate around the logic of optimization—streamlining resource flows, reducing waste, or maximizing performance. These goals matter, but they often freeze environments into static configurations, leaving little capacity for adaptation. Regenerative intelligence shifts the emphasis to systems that evolve through feedback, where materials and environments adjust to external pressures rather than resist them.

This perspective aligns design with ecological realities. Forests redistribute nutrients during stress; wetlands modulate water flows; coral reefs build architectures through interaction, not control. Regenerative intelligence treats these processes as operational models rather than metaphors.

In practice, this means designing infrastructures that learn from disturbances, not simply withstand them. It also means integrating biological actors—microbes, plants, algae, or soil systems—into built environments in ways that allow for ongoing negotiation. Instead of optimizing for a narrow set of parameters, regenerative design embraces variability, succession, and transformation.

Studio Ossidiana’s practice embodies this shift. Their work often centers on material ecologies shaped by geological, biological, and cultural dynamics—projects where matter is not inert but part of a responsive system. Their installations and landscapes explore how materials behave over time, interacting with water, light, and other species rather than holding a fixed form. By foregrounding change instead of stability, their work argues for a design approach that accepts—and leverages—environmental flux.

Designing with Living Systems, Not Around Them

Regenerative intelligence also reframes the role of living systems in design. Rather than treating biological matter as a resource or aesthetic reference, it positions organisms as active participants whose agency shapes the outcome.

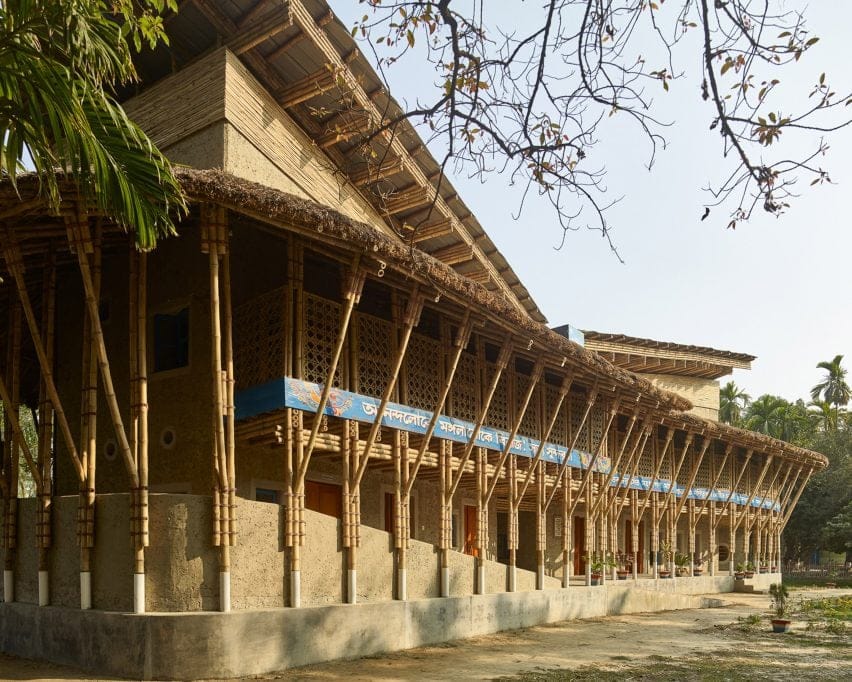

Anna Heringer’s architectural practice is a clear example. Her work with earthen construction demonstrates how local ecosystems, communities, and materials can collaborate to form resilient structures. Earthen buildings respond to humidity, temperature, and repair differently than industrial materials. They invite maintenance as a shared cultural practice and emphasize the social and ecological dimensions of building. Her projects show how regenerative principles—circularity, low-energy processes, and local ecological alignment—can produce architecture that strengthens rather than depletes environmental systems.

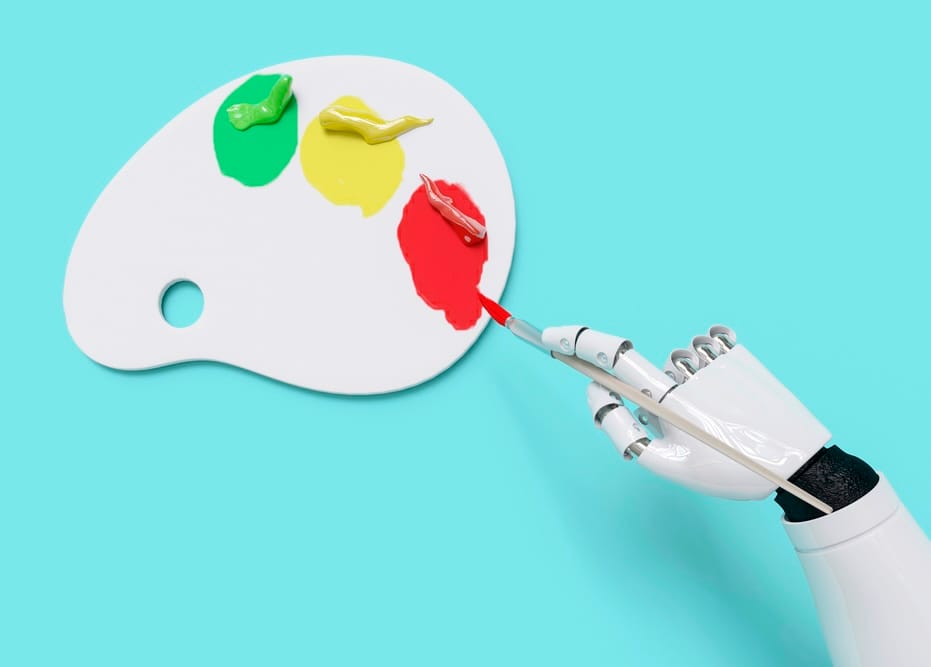

This orientation toward ecologically responsive processes is also reflected in the emerging field of biofabrication, where materials such as mycelium, algae, or bacterial cellulose become structural elements. These materials grow, metabolize, and decay according to environmental conditions. Designing with them requires accommodating biological agency, not imposing rigid parameters. The result is a move away from linear manufacturing toward metabolic cycles. Regenerative intelligence treats these cycles not as constraints but as sources of intelligence—systems that sense, respond, and heal. As climate pressures increase, this form of intelligence becomes a critical design asset.

Mapping Multispecies Realities

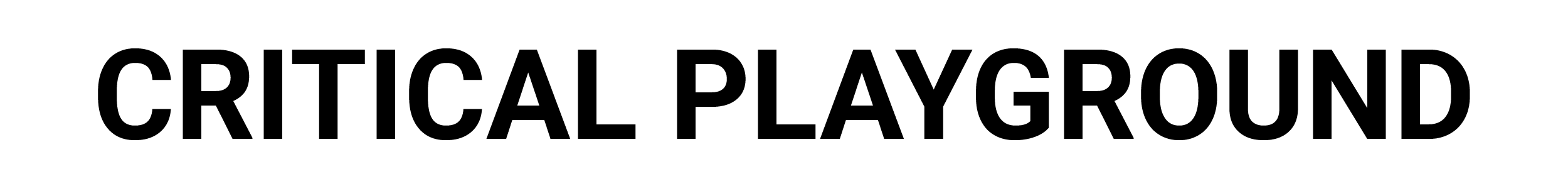

If regenerative intelligence asks designers to collaborate with living systems, it also requires a deeper understanding of the infrastructures that shape ecological relations. Feral Atlas, led by a collective of researchers and artists and published by Stanford University Press, offers one of the most comprehensive recent attempts to map these relationships. The project documents “feral” entities—organisms, infrastructures, and hybrid ecologies that have emerged from human systems but exceed human control.

Rather than presenting a stable view of environmental impact, Feral Atlas highlights the micro-politics and material entanglements that shape contemporary ecologies. It underscores how industrial infrastructures, colonial legacies, and global supply chains have produced hybrid ecosystems that cannot be reduced to either nature or technology. This form of mapping expands the scope of regenerative intelligence by revealing where design interventions need to occur and where unintended ecological actors already operate. By articulating how systems behave at multiple scales—from microbial interactions to geopolitical infrastructures—Feral Atlas offers a framework for designers working toward regenerative outcomes. It shows that resilience is not simply a material property; it is produced through entangled relationships.

Building for Resilience, Not Permanence

A critical component of regenerative intelligence is the recognition that resilience emerges from diversity, redundancy, and continuous feedback. It stands in contrast to the architectural pursuit of permanence or the technological pursuit of control. Instead of designing structures that resist change, regenerative systems absorb, redirect, and adapt to it.

Studio Ossidiana’s landscapes shift with tidal rhythms and seasonal variations. Heringer’s buildings invite maintenance as a living process. Feral Atlas reveals the way unintended ecologies form in the gaps of infrastructure. Each of these practices challenges the assumption that stability is the ultimate design goal.

Regenerative intelligence suggests that the environments most capable of withstanding climate uncertainty are the ones that can reorganize themselves. These systems are not simply efficient; they are alive in the sense that they maintain relationships, exchange matter and energy, and renew themselves over time.

For designers, this translates into a new set of priorities: designing for feedback, fostering ecological co-production, and planning for ongoing transformation. The shift is subtle but significant. Instead of asking how design can control environments, the question becomes how design can participate in ecological regeneration. As more practices engage with living systems—through biofabrication, community-embedded construction, feedback-driven landscapes, and multispecies mapping—regenerative intelligence is emerging as a foundational lens for designing the future.