As AI systems increasingly mediate access to information, services, and decision-making, trust has become a design problem—not a branding exercise. For interaction designers working with machine learning systems, transparency is no longer limited to explainability dashboards or model cards. It is expressed through interface choices, interaction flows, defaults, and the boundaries placed on what systems are allowed to do.

Across research, practice, and platform design, a growing body of work treats trust not as user compliance but as a negotiated relationship shaped by power, legibility, and accountability. Three strands of work—critical data design, participatory HCI, and applied industry research—offer concrete models for how ethical commitments can be embedded directly into AI-driven systems.

Designing Power, Not Just Interfaces

Much of the contemporary discussion around trustworthy AI focuses on technical transparency: opening black boxes, documenting datasets, or publishing system limitations. While necessary, these moves often overlook how power is exercised at the interface layer—where users encounter, interpret, and respond to AI systems in practice. Designer and researcher Catherine D’Ignazio has consistently argued that transparency without structural accountability can reinforce existing inequalities. Through projects such as Data Feminism (co-authored with Lauren F. Klein) and her work at MIT’s Data + Feminism Lab, D’Ignazio frames design as a site where values are operationalized, not merely communicated.

From this perspective, ethical AI design is less about revealing how a model works and more about deciding who benefits, who is harmed, and who has agency within a system. Interface decisions—what data is shown, what is hidden, what actions are possible, and which are blocked—become mechanisms of governance. Transparency, then, is inseparable from politics. This shifts the role of UX from usability optimization to power-aware mediation. Design choices actively shape how AI authority is perceived, challenged, or deferred to.

Participation as an Ethical Boundary

If power is encoded through design, participation becomes a primary method for rebalancing it. HCI researcher Christina Harrington has developed participatory design frameworks that center communities historically marginalized by technological systems, particularly Black and disabled communities.

Harrington’s work emphasizes that ethical boundaries cannot be retrofitted after deployment. They must be established upstream through co-design processes that surface lived experience, contextual knowledge, and alternative value systems. In AI-driven interfaces, this often means designing constraints rather than capabilities—limiting automation where it undermines human judgment, or foregrounding uncertainty instead of confidence.

Importantly, Harrington’s research demonstrates that transparency is not universal. What is considered “clear” or “intuitive” varies across cultural and social contexts. Trustworthy systems therefore require localized forms of legibility, shaped through sustained engagement rather than generalized personas. This reframes transparency as relational. Ethical UX is not achieved by exposing more information, but by aligning system behavior with the expectations and needs of the people most affected by it.

Translating Ethics into Product Systems

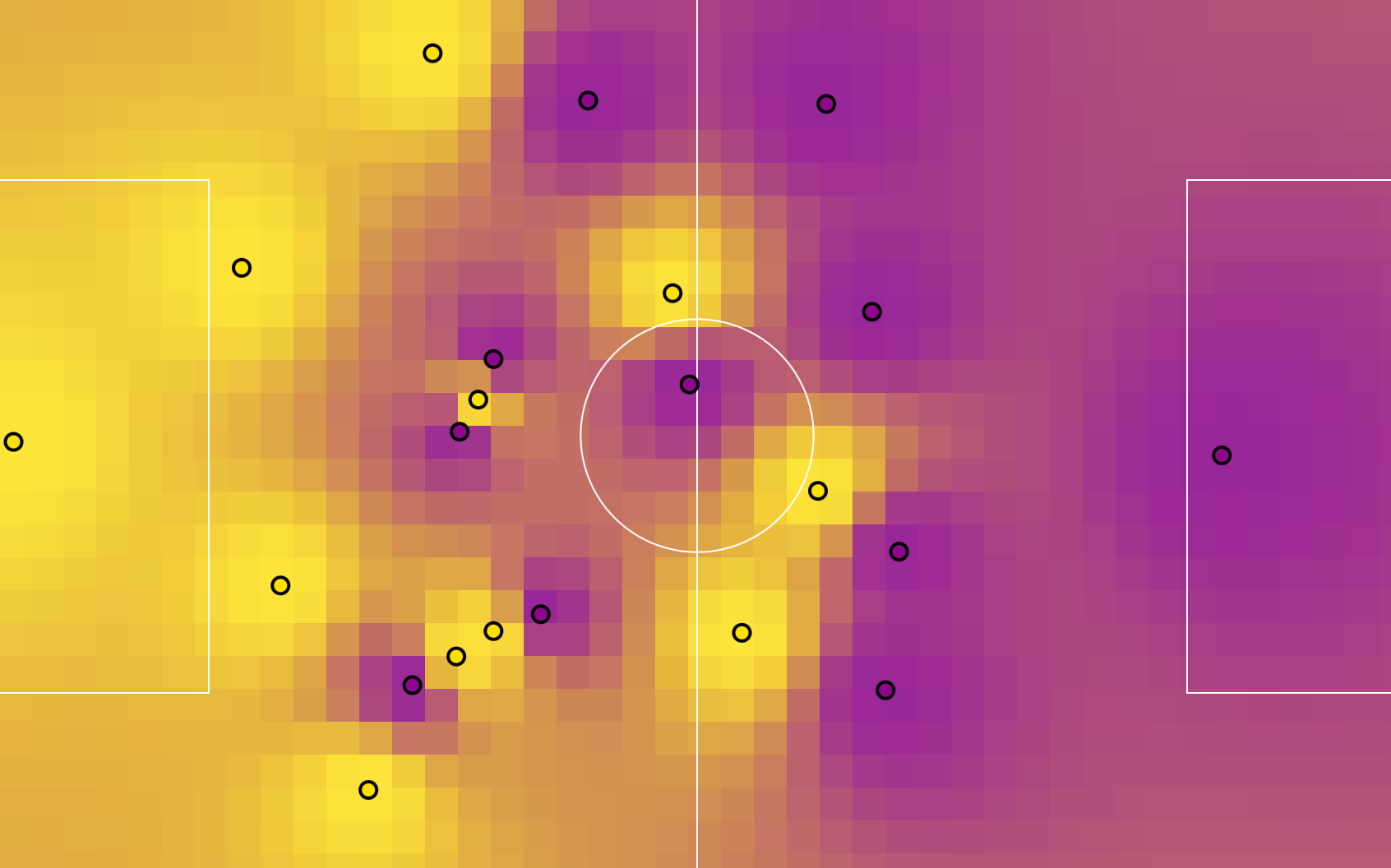

While critical and academic frameworks define the stakes, their influence on real-world platforms depends on how effectively they are translated into product development processes. This translation is the focus of Google’s People + AI Research initiative, Google PAIR, which has developed widely used tools such as the PAIR Guidebook, model transparency practices, and human-centered evaluation frameworks. Google PAIR’s contribution is not a singular ethical stance, but a set of operational methods for embedding human values into AI product teams. These include design checklists for responsible AI, participatory research protocols, and guidance on communicating system uncertainty through interface design.

Crucially, PAIR’s work treats UX designers as ethical agents within AI pipelines—not as downstream stylists. Designers are positioned to define system boundaries: deciding when automation should defer to human oversight, how confidence is communicated, and how users are invited to contest or correct system outputs. While corporate constraints inevitably shape what is possible, PAIR’s influence illustrates how ethics can move from abstract principles into repeatable design practices. Trust, in this model, is maintained not by claims of objectivity but by consistent, legible system behavior over time.

From Transparency to Accountability

Taken together, these approaches suggest that transparency alone is insufficient. Trustworthy AI systems require accountability structures that are experienced through interaction—not hidden in documentation.

The implication is clear: the politics of AI are increasingly negotiated at the UX layer. Interaction designers are not merely translating system logic for users; they are actively shaping how authority, agency, and responsibility are distributed within AI-mediated environments. Ethical boundaries—what a system can infer, recommend, automate, or refuse—are design decisions. Transparency becomes meaningful only when paired with participation, constraint, and the possibility of refusal. As AI systems continue to scale, trust will not be granted by default. It will be designed, tested, contested, and redesigned—one interface decision at a time.