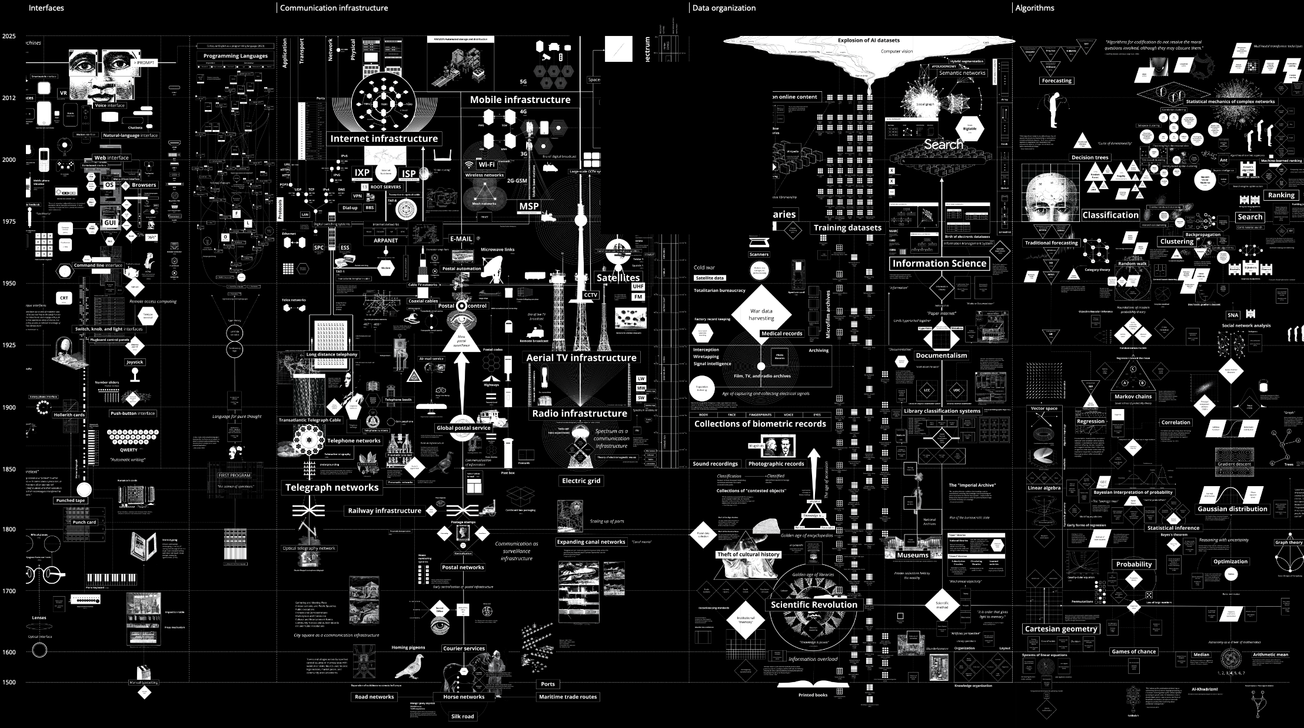

The aesthetics of machine vision don’t begin with neural networks; they begin with the dataset. As image models, recommendation systems, and civic algorithms weave into daily life, artists and curators increasingly treat datasets not as neutral inputs but as archives, lenses, and infrastructures of power. Gene Kogan, Hannah Redler Hawes and the Open Data Institute’s Data as Culture programme, and James Bridle approach this from different directions, yet all foreground the dataset as a site of authorship, control, and critical inquiry.

The Dataset as Medium, Not Just Fuel

For decades, “data” functioned largely as back-end substrate—an engineering concern that remained separate from the aesthetic decisions of designers and artists. That boundary has eroded. As machine learning becomes embedded in creative practice, the dataset itself has moved into view as an expressive and conceptual medium.

Artist and programmer Gene Kogan has been central to this shift. His long-running project ml4a (Machine Learning for Art) is a public collection of open-source code, tutorials, workshops, and an in-progress textbook designed to help artists work directly with machine learning systems. The project is explicitly described as “a collection of tools and educational resources which apply techniques from machine learning to arts and creativity,” and was initiated and maintained by Kogan as an open resource between 2015 and 2021.

Kogan has reinforced this pedagogical approach through institutional teaching, most notably his Machine Learning for Artists course at New York University’s Interactive Telecommunications Program (ITP). In that course—outlined in his Medium posts and course materials—artists and designers are introduced not only to neural network architectures and generative models but also to dataset curation, data preprocessing, and labeling practices. The emphasis is clear: critical engagement with AI requires understanding how training data conditions what a model can perceive, classify, or generate.

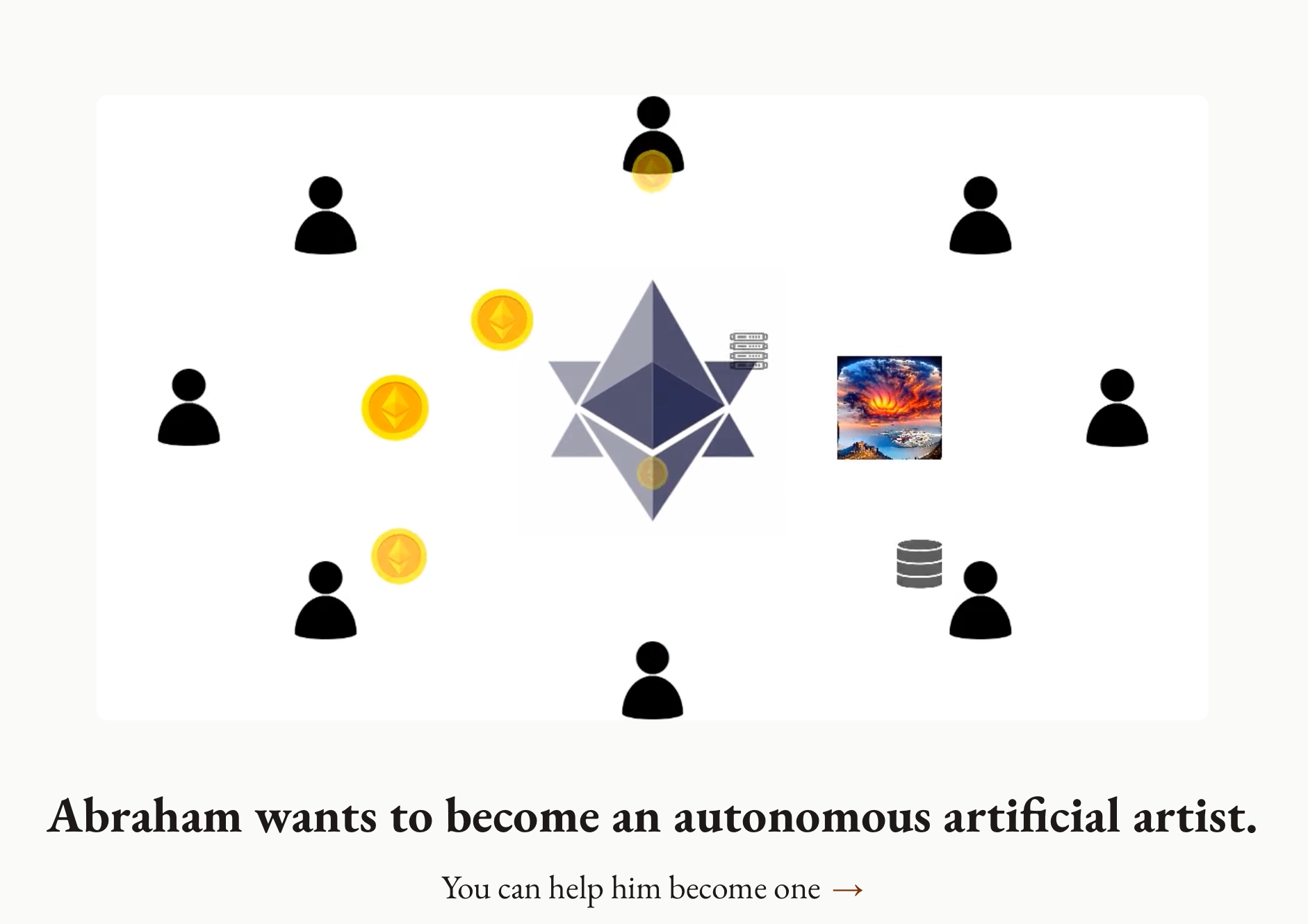

Kogan’s later research extends this argument into collaborative, decentralized systems. His project Abraham, introduced in a paper for the NeurIPS 2019 Creativity Workshop and expanded in subsequent writing, proposes an “autonomous artificial artist” built and governed by a distributed network of contributors. Abraham is conceived as a long-term, open project in which participants help design, train, and refine a generative art agent. In this model, the dataset becomes a collectively authored cultural object—its contents determining the aesthetic scope, tendencies, and biases of the artificial “artist.”

This logic reframes a foundational idea for creative AI practice: dataset authorship is aesthetic authorship. Decisions about what the machine sees—what images, languages, histories, or bodies populate its training corpus—are not neutral technical steps. They are formative aesthetic acts, shaping the system’s expressive vocabulary as directly as any gesture, material choice, or compositional decision made by a human artist.

Data as Culture: Curating Data’s Social and Civic Aesthetics

If Kogan opens up the technical stack, Hannah Redler Hawes builds institutional infrastructures around data as cultural material. As Director of the Data as Culture art programme at the Open Data Institute (ODI), she works at the intersection of contemporary art, data, and the social and ethical questions raised by digital technologies.

Data as Culture has, since 2012, commissioned and exhibited artworks that use data as an art material while interrogating its social and ethical implications. The ODI frames the programme as a way to engage diverse audiences with artists and works “that use data as an art material,” situating artistic practice alongside its broader work on open and trustworthy data ecosystems. Early commissions—documented in ODI catalogues and talks for the 2014 Data as Culture exhibition—focused explicitly on surveillance, privacy, and personal data, using pneumatic machines, satellite imagery, data-collection performances, and “knitted data discrepancies” to explore how open data and monitoring intersect with everyday life.

A key anchor for the programme’s long-term trajectory is Julie Freeman’s online work We Need Us (2014–ongoing), co-commissioned by the ODI and The Space and later exhibited with NEoN Digital Arts. The piece pulls live metadata—data about data—from the citizen science platform Zooniverse, transforming the collective activity of over a million volunteers into a dynamic environment of animated forms and sound. Rather than visualising scientific results, We Need Us focuses on the rhythms, density, and volatility of participation itself, exploring what Freeman has described as “the life of data.”

More recently, Freeman’s Allusive Protocols (2023), commissioned by Data as Culture at the ODI with support from Invisible Dust, uses kinetic, data-driven sculptures to reflect on networked infrastructure and the fragility of connectivity. The work responds directly to ODI research on power and diplomacy in data ecosystems, considering how control over protocols and networks underpins contemporary infrastructure and the distribution of power.

Across more than a decade, Data as Culture has presented over 100 works—including 27 commissions across 11 exhibitions and partnerships—and has developed research-led themes such as Copy That?, which asks how “true” the “data you” really is and how many versions of that self exist online. This is curation as infrastructural critique: datasets are treated as civic artefacts, and their aestheticisation is tied to questions of accountability, access, and governance.

James Bridle: When Datasets Become Governance

Artist and writer James Bridle pushes the aesthetics of the dataset into the domain of political technology. Known for coining the “New Aesthetic” and for books such as New Dark Age: Technology and the End of the Future (Verso, 2018) and Ways of Being (2022), Bridle traces how computation, automation, and data infrastructures reorganise perception and power.

In the solo exhibition Failing to Distinguish Between a Tractor Trailer and the Bright White Sky at NOME Gallery in Berlin (2017), Bridle took the self-driving car as a central motif. The title comes from an accident report into a fatal Tesla crash in which the vehicle’s Autopilot system failed to distinguish the white side of a tractor-trailer against a brightly lit sky—an incident widely reported as exposing limits in the car’s sensors and system design.

The exhibition gathered works that probe machine learning and machine vision: how autonomous driving systems are trained, how they “see” the world, and how those ways of seeing can fail. Bridle worked with “software and geography” to create components for his own self-driving car—an autonomous vehicle “which learns to get lost”—using freely available tools and research papers. Through installations, image series, and the video essay Gradient Ascent, which documents test drives on Mount Parnassus, the exhibition linked technical processes such as optimisation and training to questions of labour, responsibility, and the political opacity of complex systems.

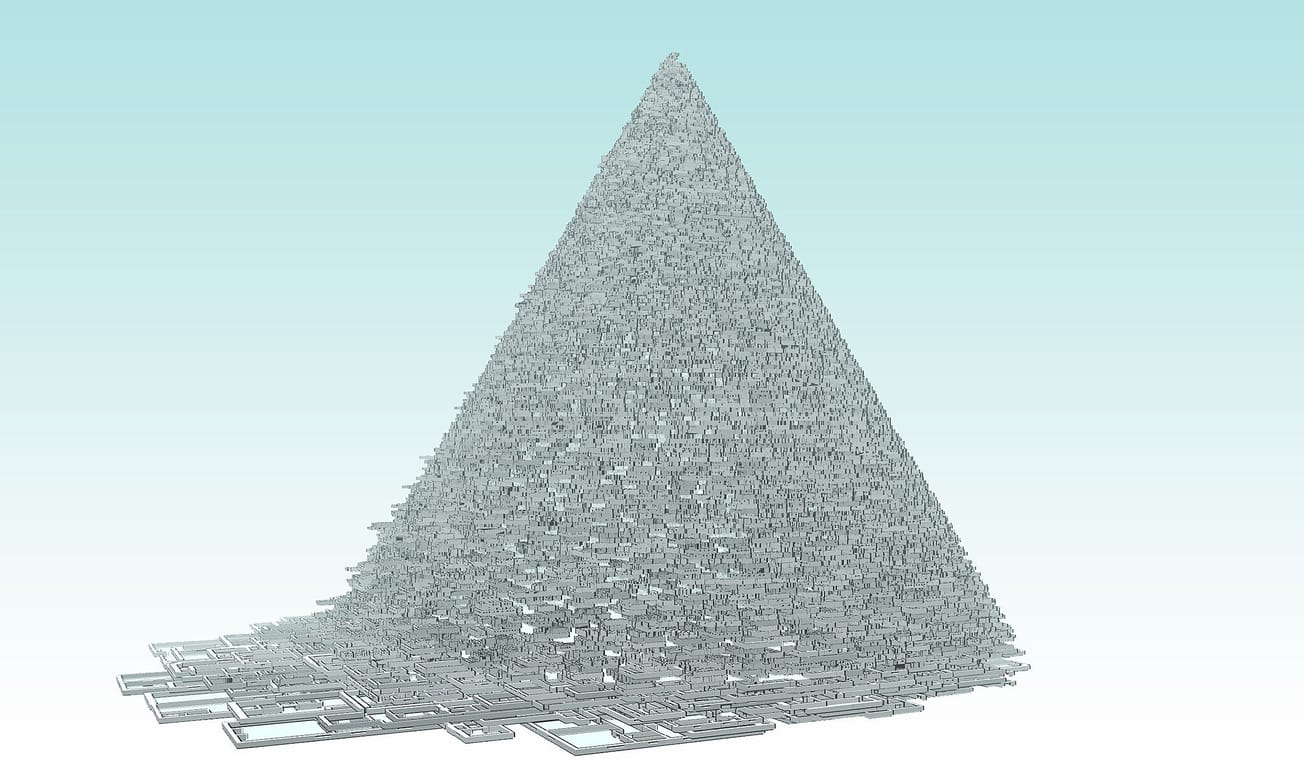

Autonomous Trap 001 (2017) condenses these concerns into a single scene: a car encircled by a salt line and road markings laid out as inward-facing “no entry” signs. As Bridle’s own description notes, the work uses ground glyphs “to trap autonomous vehicles using ‘no entry’ and other glyphs”; the car, programmed to obey those markings, cannot leave the circle without breaking its encoded rules. The trap here is not magical but infrastructural—an environmental configuration that reveals how rule-bound systems can be manipulated, and how much agency is ceded to code, training regimes, and the datasets on which they depend.

In New Dark Age and Ways of Being, Bridle extends this critique beyond the gallery. Both books argue that contemporary knowledge is increasingly routed through computational systems—search engines, models, and platforms—that are trained on vast, uneven datasets and embedded in economic and political structures. Rather than treating data as neutral input, Bridle shows how data-driven infrastructures decide what is visible, what is legible as “information,” and whose experience is excluded. In that sense, datasets become epistemological tools: they shape what counts as knowledge for human institutions and for machines alike, and their blind spots often mirror the social and environmental hierarchies in which they are produced.

Curating the Machine’s Eye

Taken together, these practices point to a shared cultural shift. Kogan equips artists and designers to work directly with training data and models, treating machine learning literacy as a creative skill set. Redler Hawes and the Data as Culture programme develop public-facing contexts in which data-driven artworks are exhibited, questioned, and contextualised—from live metadata works such as We Need Us to commissions that address energy systems, connectivity, and the power dynamics of networked infrastructures. Bridle, meanwhile, shows how training data, sensor inputs, and encoded rules can function like policy in practice, influencing what systems are able to perceive, how they behave, and where their failures become visible.

For a design-savvy, technologically fluent audience, this is the real frontier of AI aesthetics. Style transfer and text-to-image prompts represent only the surface layer. The deeper work lies in curating the machine’s eye: determining which archives matter, which signals count as noise, whose worlds become legible to computation, and how those decisions are opened up to scrutiny, collaboration, and repair. The aesthetics of the dataset are, ultimately, the aesthetics of the systems we build—and the futures we enable through them.